On a humid May afternoon in Surat, I was teaching a module to a cohort of MBA students. Most were in their late twenties, poised to inherit enterprises that stretched from the wholesale textiles markets of Surat to the trading floors of Dubai, from chemical plants in Gujarat to boutique hotels in Malaysia. A few managed family interests in Europe, shuttling between London, Antwerp, and Ahmedabad with the same ease as their parents once moved between state capitals in India.

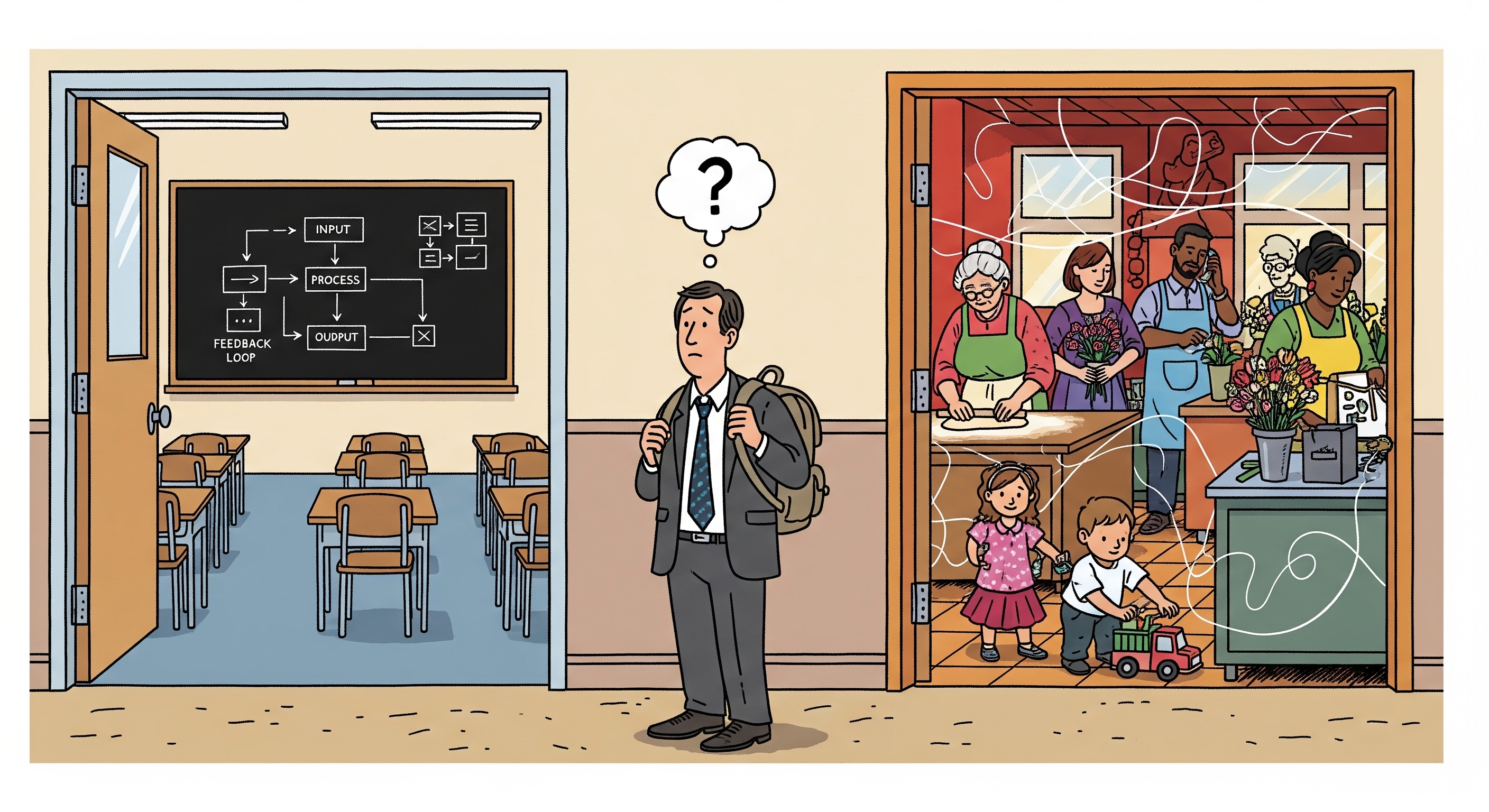

During the break, the conversation shifted from our case study on a Fortune 500 conglomerate to something more pressing. One student said quietly, “Sir, I do not think any of this will help when I get back.” Others nodded. Their reasons varied. Some said the frameworks assumed a clear separation between ownership and management. Others felt the neat prescriptions ignored the messy realities of running a business where the CEO might also be an uncle, the CFO a cousin, and the largest shareholder a grandmother.

I had heard similar reflections in Ahmedabad from students of long-established industrial houses, and in Kanpur from wholesale leather suppliers balancing global supply chains with kinship obligations that crossed continents. All had one thing in common. Their family businesses, the kind they were destined to run, were little more than footnotes in their MBA curriculum, which was training them for a corporate world.

I. The Scale and Centrality of Family Capitalism

This gap is not a marginal concern. In India today, approximately 300 business families generate an estimated ₹7,100 crore in value every day (Hurun India, 2024). These enterprises, from Reliance Industries to the Murugappa Group, are embedded in sectors such as energy, manufacturing, finance, and retail. They shape the flow of capital, influence employment systems, and anchor regional economies (Khanna & Palepu, 2005).

Globally, the parallels are striking. In Germany, the Mittelstand of family-owned small and mid-sized enterprises drives industrial exports (Berghoff, 2006). In Italy, industrial districts dominated by family firms sustain globally competitive textile and manufacturing clusters (Becattini, 1990). In South Korea, the chaebols such as Hyundai, Samsung, and LG remain family-controlled conglomerates with worldwide influence (Chang, 2003). In the United States, dynasties such as the Waltons of Walmart and the Fords of Ford Motor Company demonstrate that family capitalism is not a relic of the past but a central force in advanced economies (Colli & Rose, 2008).

Family ownership is not an “emerging market” anomaly. It is a systemic feature of capitalism in diverse geographies and at different stages of economic development (Colli, 2016; Morck & Yeung, 2004).

II. Why the Curriculum Ignores Them

The absence of family business studies from the core MBA curriculum is not accidental. The intellectual foundations of modern management education emerged in early 20th-century America, during the rise of large corporations such as General Motors and DuPont. These companies were professionally managed and widely held. Academic frameworks evolved around agency theory, the principal–agent problem, and market-based governance (Hansmann & Kraakman, 2001).

In this worldview, the shareholder was the owner, the manager the agent, and the separation between the two the central challenge to solve. Governance was taught as a matter of aligning these interests. The role of kinship, succession, and intergenerational capital stewardship was either absent or treated as a special-interest topic. For much of the world, where ownership and management are intertwined through family ties, the dominant model was both alien and incomplete.

III. The Cost of the Blind Spot

The cost of this blind spot becomes visible the moment graduates return to their family enterprises. In Mumbai, a student preparing to lead her family’s logistics company told me she had no framework for mediating between two branches of the family with conflicting strategic visions. In Ahmedabad, an heir to a chemicals empire described his difficulty in introducing non-family executives without triggering fears of losing control. In Surat, a diamond trader’s son wished his “Leadership” course had included at least one case on how to remove an underperforming cousin without rupturing family relations.

The consequences of such unpreparedness are not hypothetical. The split between Mukesh and Anil Ambani in the 2000s, which divided Reliance Industries, reshaped Indian capital markets and altered the trajectories of two global-scale enterprises. In South Korea, inheritance battles within the Samsung family triggered public scrutiny, shareholder lawsuits, and political fallout. In Europe, the Gucci family’s disputes nearly destroyed one of the world’s most iconic luxury brands before outside investors intervened. These are reminders that succession failures and governance missteps in family firms can have national, even global, economic consequences.

These are not soft issues. They go to the heart of organizational stability, strategic coherence, and long-term competitiveness. When graduates trained for dispersed-shareholder corporations step into majority-owner firms, they often adopt one of two flawed approaches. Some import generic corporate templates designed for a different ownership structure, producing governance systems that do not fit. Others fall back on ad hoc decision-making shaped by habit, tradition, or the preferences of the most powerful family member. Neither path is conducive to sustainable growth (Carney, 2005).

IV. Partial Recognition and the Limits of Electives

To their credit, some institutions have recognized this gap. INSEAD, Kellogg, and the Indian School of Business, including several IIMs, have developed dedicated family business programs that address governance structures, succession planning, professionalization, and conflict resolution (Gersick et al., 1997).

Yet these initiatives remain on the periphery. They are offered as electives, housed in specialized centers, or framed as supplementary learning. The implicit message is that family business is a niche concern, secondary to the “real” disciplines of strategy, finance, and marketing, which remain built around the public corporation model. Students can complete an MBA without seriously engaging with the dynamics of family-controlled enterprises. Electives, by their very design, signal “optional.” They mark family business as exceptional rather than central; an academic categorization that reproduces the marginalization of family capitalism in pedagogy.

V. Reimagining the Core

If management education is to reflect the world as it exists, family business studies must be embedded in the core curriculum. This requires redesigning mainstream courses so that they speak to both public corporations and family-controlled firms.

- Strategy should address how competitive advantage is sustained across generations and succession cycles.

- Finance should examine capital structures in closely held firms, dividend policies shaped by family needs, and financing generational transitions.

- Organizational behavior should consider kinship dynamics, informal authority, and integrating professional managers into family cultures.

- Governance should cover family constitutions, shareholder agreements, and succession protocols, alongside board composition rules for listed companies.

The case method should not be restricted to Silicon Valley start-ups or Wall Street conglomerates. It should include the strategic dilemmas of a German Mittelstand firm, a Korean chaebol, an Italian industrial family, and a multinational family conglomerate from India.

VI. Why This Matters Beyond Business Schools

This is not merely a matter of academic alignment. Family-controlled enterprises are major employers, investors, and political actors. They shape labor markets, influence tax regimes, and steer investment flows. Ignoring them in elite management education perpetuates a distorted understanding of capitalism among future leaders, policymakers, and analysts.

In India and much of the world, family firms account for a large share of GDP and millions of jobs. A generation of leaders who are unprepared for the realities of family capitalism risks repeating governance failures, mismanaging succession, and missing opportunities for innovation and international expansion. The economic and social costs of such failures extend far beyond the firm into markets, communities, and even state policy.

VII. Teaching the World as It Is

Family businesses are not transitional forms on the way to the “modern” corporation. They are adaptive, resilient, and central to the global economy. Treating them as marginal in management education is a disservice to students, employers, and societies.

Redesigning the core curriculum to reflect the realities of family capitalism is not about nostalgia for tradition. It is about ensuring that what we teach matches how the world actually works. If business schools continue to ignore family capitalism, they risk producing graduates who are irrelevant to the very economies they claim to serve. My students in Mumbai, Ahmedabad, and Surat often remind me that they do not have the luxury of learning the realities of their enterprises by trial and error. Business schools should not have the luxury of teaching a model of capitalism that exists mostly in theory.

References

- Anderson, R. C., & Reeb, D. M. (2003). Founding-family ownership and firm performance. Journal of Finance, 58(3), 1301–1328. https://doi.org/10.1111/1540-6261.00567

- Becattini, G. (1990). The Marshallian industrial district as a socio-economic notion. In F. Pyke, G. Becattini, & W. Sengenberger (Eds.), Industrial districts and inter-firm co-operation in Italy (pp. 37–51). International Institute for Labour Studies.

- Berghoff, H. (2006). The end of family business? The Mittelstand and German capitalism in transition, 1949–2000. Business History Review, 80(2), 263–295. https://doi.org/10.2307/25097196

- Carney, M. (2005). Corporate governance and competitive advantage in family-controlled firms. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 29(3), 249–265. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6520.2005.00081.x

- Chang, S. J. (2003). Ownership structure, expropriation, and performance of group-affiliated companies in Korea. Academy of Management Journal, 46(2), 238–253. https://doi.org/10.2307/30040617

- Colli, A. (2016). Family firms in the long run: Theoretical and historical perspectives. Cambridge University Press.

- Colli, A., & Rose, M. B. (2008). Family business. In G. Jones & J. Zeitlin (Eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Business History (pp. 194–217). Oxford University Press.

- Faccio, M., & Lang, L. H. (2002). The ultimate ownership of Western European corporations. Journal of Financial Economics, 65(3), 365–395. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0304-405X(02)00146-0

- Gersick, K. E., Davis, J. A., Hampton, M. M., & Lansberg, I. (1997). Generation to generation: Life cycles of the family business. Harvard Business School Press.

- Hansmann, H., & Kraakman, R. (2001). The end of history for corporate law. Georgetown Law Journal, 89(2), 439–468.

- Hurun India. (2024). Hurun India Rich List 2024. Hurun Report.

- Khanna, T., & Palepu, K. (2005). The evolution of concentrated ownership in India: Broad patterns and a history of the Indian software industry. In R. Morck (Ed.), A history of corporate governance around the world: Family business groups to professional managers (pp. 283–324). University of Chicago Press.

- La Porta, R., Lopez‐de‐Silanes, F., & Shleifer, A. (1999). Corporate ownership around the world. Journal of Finance, 54(2), 471–517. https://doi.org/10.1111/0022-1082.00115

- Miller, D., & Le Breton-Miller, I. (2005). Managing for the long run: Lessons in competitive advantage from great family businesses. Harvard Business School Press.

- Morck, R., & Yeung, B. (2004). Family control and the rent-seeking society. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 28(4), 391–409. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6520.2004.00053.x

- Villalonga, B., & Amit, R. (2006). How do family ownership, control, and management affect firm value? Journal of Financial Economics, 80(2), 385–417. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfineco.2004.12.005