The bullet was the means of physical subjugation. Language was the means of spiritual subjugation. Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o

The world has lost a colossus. Not merely a writer, but a cultural warrior, an uncompromising decolonial voice, and a luminous mind who refused to let colonial modernity be the final story Africa told of itself. Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o’s passing is not simply a moment for mourning. It is a moment for reckoning. Reckoning with what we have done with the legacy of decolonization. Reckoning with the power of language to liberate or to enslave. Reckoning with the quiet violence of forgetting.

Born in 1938 in Kamiriithu, Kenya, Ngũgĩ entered the world during one of its most volatile junctures - when the colonial project was at once tightening its grip and preparing for its long sunset. Educated in colonial schools like Alliance High School, he was baptized James Ngugi and inducted into what he later called the “colonial metaphysical empire”: the mental architecture of English supremacy and African shame. He recalled that those who dared speak Gĩkũyũ, his mother tongue, were publicly punished.

Language, even then, was not merely a tool. It was a map of the world. The one that erased African rivers and re-inscribed European roads.

But Ngũgĩ would not remain James. He would turn away from the English language and the European name, and begin a long and difficult pilgrimage back to Gĩkũyũ, back to Africa, and back to himself.

Decolonising the Mind: A Manifesto for the Colonized World

Ngũgĩ’s seminal work, Decolonising the Mind (1986), is perhaps one of the most powerful indictments of colonial education and its lingering aftermath. For him, language was not simply a medium of instruction but the medium of consciousness. He famously wrote:

Language, any language, has a dual character: it is both a means of communication and a carrier of culture … The domination of a people’s language by the languages of the colonising nations was crucial to the domination of the mental universe of the colonised.

This was not simply linguistic theory but a moral call to arms. While postcolonial elites debated development policy and national planning, Ngũgĩ insisted that the real battle was upstream: in the soul. A people who do not speak in their own voice can never walk in their own direction.

Ashis Nandy once wrote,

The West is not in the West. It is a project, not a place.

Ngũgĩ understood this. The West, through English and French, and Portuguese, had taken up residence in the minds of African children, not just through syllabi but through syllables. “Colonial alienation,” he argued, “is like producing a society of bodiless heads and headless bodies.” Without language, thought is amputated. Without thought, action becomes mimicry.

The Price of Integrity

Ngũgĩ did not merely theorize decolonization - he lived it. His decision to abandon English as his literary language was not a quiet academic choice. It was a rupture. When he co-wrote and staged Ngaahika Ndeenda (I Will Marry When I Want), a powerful play in Gĩkũyũ about land dispossession and class betrayal, the post-independence Kenyan state - still wearing colonial gloves - imprisoned him without trial in 1977. The British Empire had exited in form, but not in function. He was released a year later, but continued to be harassed and eventually went into exile, first to the UK and then to the United States.

He once remarked that the African elite “inherited the flag but not the soul.” In Moving the Centre, he writes with precision:

The African bourgeoisie that inherited the flag from the departing colonial powers was created within the cultural womb of imperialism... Even after they inherited the flag, their mental outlook … tended to be foreign.

His critique was not just of European colonialism, but of the postcolonial mimicry it spawned - what VS Naipaul once called “mimic men,” though Naipaul’s cynicism often lacked the empathetic clarity that Ngũgĩ maintained.

A Literary Giant Denied by the West

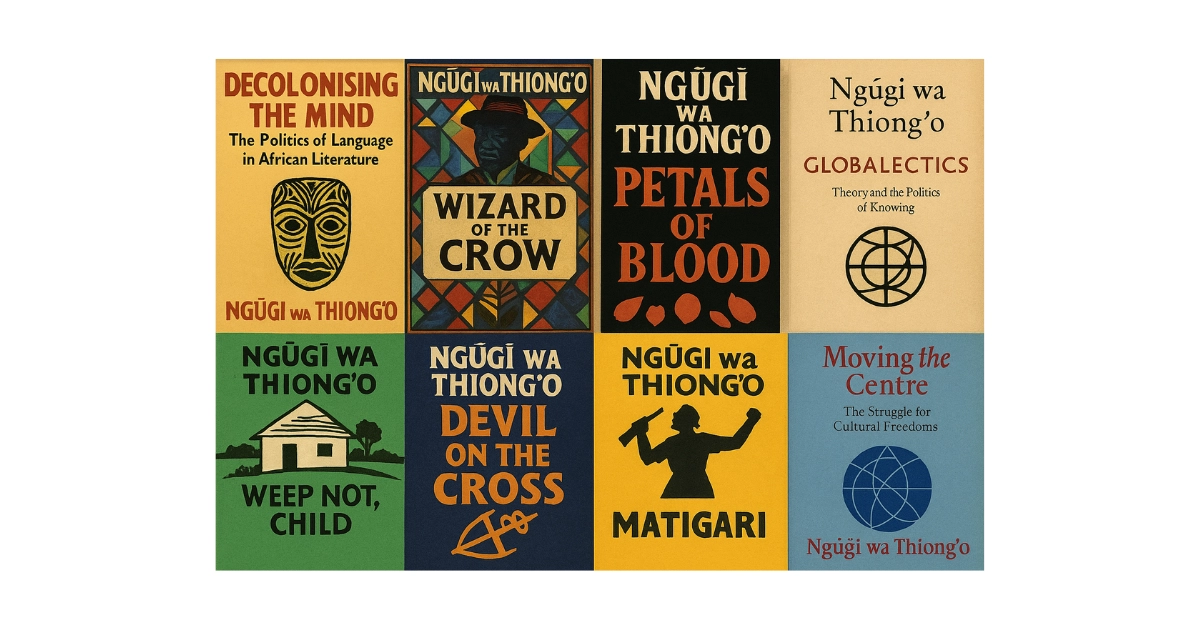

Year after year, Ngũgĩ’s name was floated for the Nobel Prize. Year after year, the Swedish Academy passed him over - for safer, more cosmopolitan, more Euro-accommodating voices. In denying him, the Nobel Prize only denied itself the chance to honour one of the greatest literary thinkers of our time. For Ngũgĩ’s oeuvre - Weep Not, Child, Petals of Blood, Devil on the Cross, Matigar, Globalectics - were not just a set of African stories. It was a theory of the world.

In Globalectics, he challenges the imperial logic of center-periphery:

The globe is not a set of concentric circles with a single centre. It is an interconnected whole of many centres in dialogue with one another.

Compare this with Dipesh Chakrabarty’s plea to Provincialize Europe, to liberate historical thinking from the assumption that Europe is the standard and others are deviations. Ngũgĩ did not provincialize Europe - he re-villaged Africa. He called for the village not to shrink under globalization, but to become a cosmos in its own right.

Why Ngũgĩ Still Matters

In an age when English-medium education is aggressively marketed across Asia and Africa, when Indian children are still shamed for speaking Bhojpuri or Kannada or Maithili in school, when African authors are told to “write for the global market” - Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o remains devastatingly relevant.

He is not merely an African voice. He is a planetary voice speaking from the periphery to the center, only to remind the center that it is not the whole.

In India, his voice echoes the struggles against Macaulay’s Minute. His voice echoes what Ashis Nandy calls “the uncolonized mind”, which is now quickly becoming an endangered species. His voice echoes against the loss of mother-tongues, in the name of employability. His critique of cultural erasure and elite complicity finds resonance in the heart of India’s own language debates and educational dilemmas.

His was the life of a satyagrahi of the pen - one who turned away prestige, wealth, and fame for fidelity to truth. He chose exile over compliance. Gĩkũyũ over English. Memory over mimicry.

A Language Warrior’s Legacy

In his later years, he wrote:

Languages are like musical instruments. You don’t say, "Let there be a few global instruments, or let there be only one type of voice all singers can sing.

In the orchestra of world literature, Ngũgĩ played the Gĩkũyũ lyre with fierce devotion. And in doing so, he reminded us that the future of humanity will not be monolingual, monocultural, or monochromatic.

Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o did not win the Nobel Prize. But perhaps the Nobel never deserved him. As Tagore, another decolonial prophet once reminded us, true greatness is not conferred by medals. It is conferred by memory.

May the seeds Ngũgĩ sowed in the language of his ancestors rise as forests in the minds of the unborn.

“Secure the base,” he said. And now that he has returned to it, it is up to us to till its soil.

A portrait of Ngũgĩ in his Kenyan surroundings, which beautifully captures his spirit.

A portrait of Ngũgĩ in his Kenyan surroundings, which beautifully captures his spirit.