Aseem Shrivastava is a writer, scholar, and ecological thinker whose work straddles the intersection of economics, ecology, and philosophy. Trained in economics at Delhi University and University of Massachusetts, Shrivastava brings a rare clarity and moral urgency to the question of how modern economic systems are fundamentally misaligned with the well-being of the earth and its people. He is best known for co-authoring Churning the Earth: The Making of Global India (2012), a searing indictment of development in India. In his more recent (and upcoming) works, Shrivastava deepens this critique through the novel lens of ecosophy - a term that connotes a synthesis of ecology, wisdom, and philosophy. Shrivastava's ecosophy is not simply an academic theory, but a worldview - a call to reimagine the roots of human beings flourishing in harmony with the Earth.

The focus of the present review, Grammar of Greed: Reflections on a Fatal Ecology, is a powerful expansion of this ecosophical vision, exploring how language and cultural narratives have normalized and perpetuated greed, avarice, and excess, leading to the prevailing worldview that sees nature as a resource to be exploited. Structured as a collection of meditative and reflective passages organised around a few key themes (titled 'The Warp of War’, 'The Curse of Conquest, and 'The Seduction of Speed’), the book interrogates the ideological underpinnings of contemporary capitalism and on a deeper level, the perils of modernity itself, and exposing the ubiquity of greed which has indeed been grammatically encoded into the very language of modern existence. The author asks us to listen closely to the moral lacunae and conceptual assumptions that dominate our economic and cultural discourse. To Shrivatsava, the prevailing economic and developmental paradigms that prioritize exploitation and consumption have led to ecological degradation and a loss of spiritual and cultural connection to the Earth and our own communities and families.

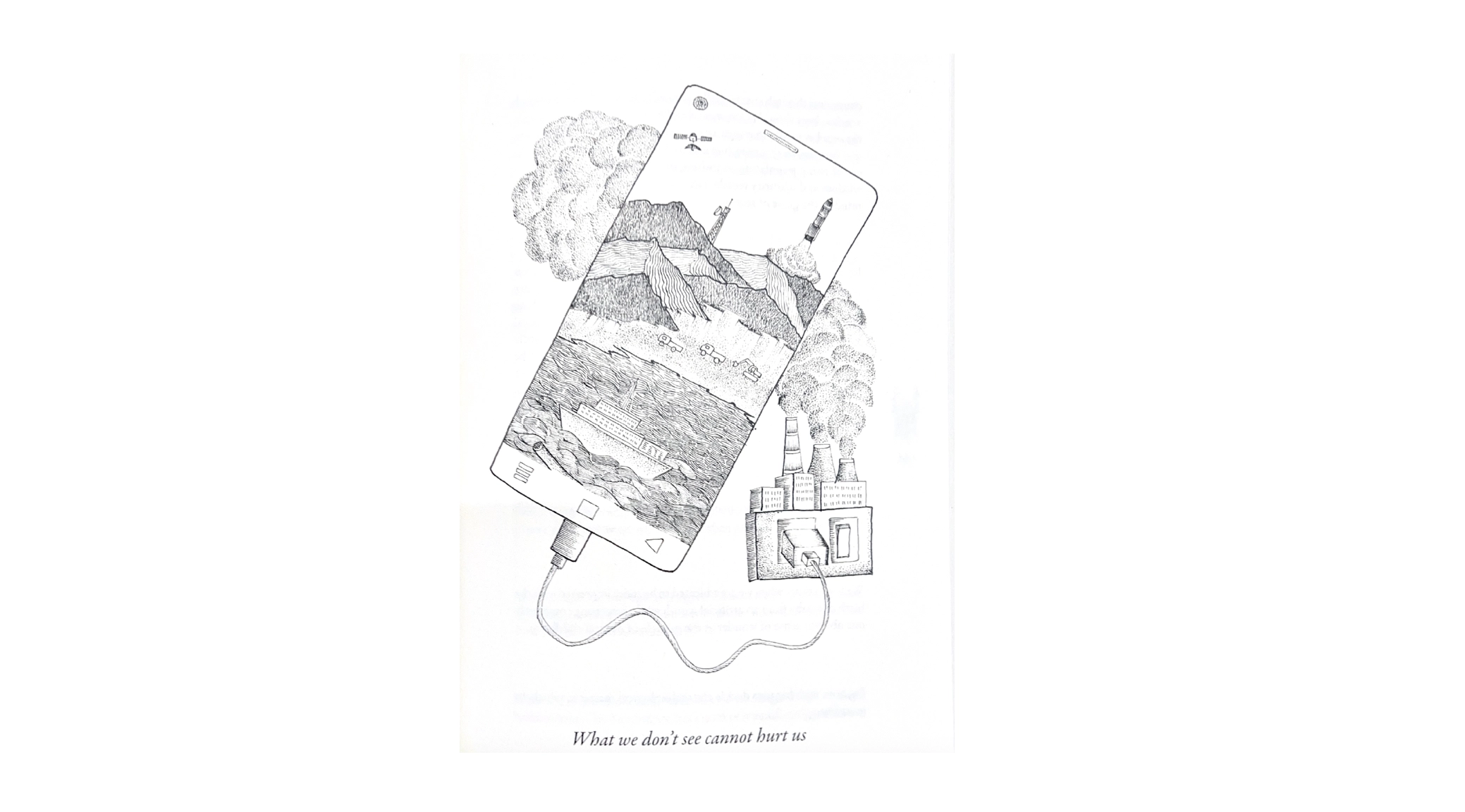

The book is not merely a critique, however. It is also an invitation: to recover older, marginalized traditions of thought - spiritual, ecological, philosophical - that offer radically different grammars for understanding life, community, and the Earth. It is organised not as a continuous narrative but as a series of reflections and highly quotable aphorisms followed by deliberate pauses - as he calls on the reader to ponder over every passage - making it a truly contemplative exercise. The text is punctuated by illustrations of Gond artist Sachin Vyam, whose work adds an intriguing cultural depth to Shrivastava's prose.

The first chapter of Grammar of Greed, titled ‘The Warp of War’ sets the tone for Shrivastava’s diagnosis of modernity as a system rooted in endless conquest, cloaked in the rhetoric of progress and a false sense of security arising from the promise of freedom. He traces a philosophical and material transformation - how finite wars of the past - once waged for tangible ends - have morphed into a perpetual, systemic warfare driven by insatiable corporate and/or elite greed. Shrivastava delves into the manner in which our very ways of thinking, feeling, and relating have been colonized by the logic of markets and competition and also dwells on how speech has lost its power, the hollowing out of community, and the commodification of both knowledge and human connection. Through this, Shrivastava invites us to confront not only the structural violence of modernity, but also the cognitive and emotional disfigurement it has normalized.

In the subsequent chapter, Shrivastava turns his philosophical gaze toward the civilizational psyche of modernity, foregrounding its pathological deviation from abundance to excess. He argues that whereas abundance connotes balance, sufficiency, and reciprocity with the natural world; excess, the operative mode of modernia and which rests on extraction, generates scarcity elsewhere, and culminates in the generation of waste.

A culture of excess is thus fundamentally unsustainable, driven by an insatiable appetite that erodes both ecological and cultural foundations.

This logic of excess is intimately tied to the legacy of conquest, which, Shrivastava contends, leaves enduring fissures in both the conquering and conquered cultures which do not merely transform; they undergo a profound internal alienation. The conquered are coerced into mimicking the conqueror, often at the expense of their own civilizational integrity. This mimicry, mistaken as progress, yields a tragic parody: a culture that represses its own traditional ecological wisdom, dissolves its community bonds, and pursues the illusory dream of “development.” Such historical amnesia blinds societies to the structural violence of modernity and traps them in cycles of imitation, superficialization, and internal decay. He writes that -

Finding fault with traditional cultures is a convenient way for modernity to install its own formidable power over human societies.

Shrivastava then turns his attention to the epistemic superiority claimed by literate, modern cultures, suggesting that a culture truly in tune with the wholeness of life might not have the impulse to obsessively record. In this light, the museum becomes a melancholic symbol—not of cultural preservation, but of cultural death by stating that -

If you never destroyed cultures, you would never have to build museums.

He thus offers a poignant critique of the modern impulse to archive what was first annihilated.

To him, the physical manifestation of the grammar of greed is expressed in world-class airports, luxury hotels, expressways, and overflowing supermarkets - emblematic of civilizational excess. These structures, celebrated as icons of progress, are in fact monuments to systemic ecological devastation and cultural dispossession, attested to by massive landfills and uprooted communities. Modernity, according to Shrivastava, simultaneously masks and amplifies the failings of the traditions it supplants.

By repressing tradition without resolving its underlying tensions, it often provokes more virulent forms of resistance - seen today in the global rise of religious fundamentalism.

Shrivastava also articulates a powerful metaphysical claim: that greed functions as a “false infinite”, a perverse simulacrum of the sacred, by drawing our collective consciousness away from the true Infinite, which remains inaccessible in a state of ignorance. He writes -

The true Infinite shall remain an abstraction to us as long as the false infinite is real for us.

This restless avarice, hardwired into our consumption-driven societies, obscures our capacity for genuine spiritual and ecological attunement. In such a condition, we are tragically exhorted to consume more in order to remedy the very crises that consumption itself has created.

In the final chapter, Aseem Shrivastava introduces the concept of transnature as a critical framework for understanding the engineered, hyper-technologized environments that now constitute the dominant living conditions of metropolitan life. Transnature refers to the vast, constructed world of modernity - comprising everything from skyscrapers, mobile technologies, and manicured urban parks to satellite networks and optic fibre cables - that is materially derived from nature but epistemically and experientially alienated from it.

While transnature remains ontologically dependent upon the natural world, it assumes an autonomous structural presence, effectively obfuscating the ecological violence and extractive brutality underpinning its existence.

Shrivastava contends that transnature has replaced nature as the primary experiential and existential context of human life, even as it remains parasitic on the natural world it renders invisible. Its opacity is both material and ideological: the processes of extraction and degradation it entails are systematically hidden from the consciousness of those who inhabit its domains. Within this framework, the modern discourse surrounding sustainability becomes a narrowly anthropocentric effort to prolong the privileges of transnature, severed from the ecological reciprocity and ethical continuity that once governed traditional lifestyles. Ultimately, transnature is the spatial and technological expression of modernity’s will to dominate, colonizing not only earth’s resources but also the very conditions of human perception, memory, and relationality.

In his Epilogue, titled The Paradise We Hide, Shrivatsava adopts a tone of sombre reflection, resisting both romanticisation of the past and the glorification of the future. While acknowledging that history has never been devoid of exploitation or injustice, he contends that earlier epochs were nevertheless ecologically more hospitable: an Earth less saturated with synthetic poisons, humanity less invasive in its technological dominion over life, and more conducive to the thriving of diverse forms of existence. The reference to a time before plastic, petrochemicals, and radioactive contamination is not a nostalgic plea but an ecological indictment of the present.

Modernity, he argues, is rapidly approaching its toxiclimax: a terminal crisis of industrial civilisation marked by irreversible ecological degradation.

In such a context, he warns against the techno-utopian delusions of escape velocity and extraterrestrial colonization, which he dismisses as adolescent fantasies peddled by techno-evangelists. Instead, he asserts that humanity is ensnared in a global impasse, a “cul-de-sac sans pareil,” where neither regression to the past nor projection into a technological future offers genuine reprieve.

The way forward, Shrivastava suggests, lies not in external solutions, but in an inward turn: a radical introspection, both individual and collective, into the inner impoverishment that has accompanied our material excess.

The “invisible treasures of the heart and the soul” have been bartered for “cheap trinkets,” leaving modern civilisation spiritually bankrupt even as it appears materially opulent.

If there appears to be any salvific possibility, it emerges not from radical technological solutions but from the renewal of consciousness, one capable of discerning which problems may be resolved and which must be accepted, endured, or relinquished.

In his final metaphor, drawn from the German concept of zugzwang, a situation in chess where any move worsens one’s position, Shrivastava encapsulates the existential dilemma of our age. We are at a juncture where all the choices now available to us risk compounding the damage already done; the imperative now is to choose the path that minimises further loss. This epilogue, then, is a contemplative plea: to reckon with the ruinous trajectory of modernity by first confronting the moral and spiritual disarray within. All in all, Shrivastava’s work offers a trenchant critique of industrial modernity; exposing the ecological, cultural, and spiritual costs of a civilisation enthralled by excess, conquest, and technological abstraction. His call is not for regression or utopian escape, but for an inward reckoning, a renewal of consciousness that can confront the crises of our time with humility, restraint, and ethical clarity.

Following are a few passages from Grammar of Greed that particularly stood out for their insight. These that offer a glimpse into Shrivastava’s deeply reflective and uncompromising critique of our life and times.

The global condition of the twenty-first century is not humanity versus nature, as is usually believed, but big capital versus the elements, with all the rest of us, including the entire natural world, caught in the crossfire. Global power flirts with the elements - and, in the bargain, condemns all humanity and nature to a perpetuity of ecological unfreedom, for the elements work through nature, which includes the elements as they work through us too!

Hannah Arendt wrote three generations ago that we were already living in a world in which speech had lost its power. Following on the heels of speech, silence too has been rendered inert in our times. Digitised outrage survives. And when that loses strength, mere rage and war follow.

The departmentalisation of knowledge and the apartmentalisation of life have accompanied each other. They both feed the isolation necessary for global structures of power to continue to prevail. How do we view ourselves and the world around us in such a way that we keep reproducing this condition? What is the cognitive truth of this historical process?

The meticulous organisation of respectable competitive gluttony is what is euphemistically understood to be a global corporation today.

Ecological sentience is inconsistent with high modernity.

The primary legacy of a culture of conquest is the eliminationist ethos of modernity.

Speed and acceleration warp the human imagination. Their psychosomatic consequences are part of what we may call the arrhythmia of modernity. Arrhythmia arises when we fall out of rhythm with ourselves and our living contexts, spatio-temporal, ecological, cultural, and psychic.

Abundance is not the same as excess. Modernia is about excess. A culture of excess generates a disposable society and a vast economy of waste. It is not about abundance. Excess rests on extraction. It is necessarily accompanied by scarcity elsewhere. Abundance does not generate such imbalances.

Finding fault with traditional cultures is a convenient way for modernity to install its own formidable power over human societies.

Modernity is the illusion that the injustices of tradition can be swept aside at one stroke.

We are encouraged today to resort to consumption to solve the problems that consumption has created.

A society that compels the middle-aged and the elderly to forget their age and behave as though they will be eternally young has so disrupted the relationship between time and eternity that it understands neither. It is condemned to perpetual juvenilia.

The microbe, the gene, the atom, the chip...they have all transformed the world in countless ways. And yet, human prejudice is such that we still continue to believe that what is bigger and larger is more real. We think that skyscrapers and expressways, shopping plazas and fancy airports are far more real than what eludes our everyday vision.

Never in the annals of recorded time has humanity generated as much garbage - both physical and metaphysical - as it has today. It is as though not just Mother Earth but our own bodies and minds have an unlimited capacity to be inhabited by landfills.

For those interested in purchasing a copy of the book, the softcover version is available at the following links:

To order a hardcover copy, write to the author at thegrammarofgreed@gmail.com.