This piece is part of a larger series by the author. Previous parts in the series can be accessed here:

- World Civilizations - Mesopotamia, Part 1

- World Civilizations - Mesopotamia, Part 2

- World Civilizations - Mesopotamia, Part 3

- World Civilizations - Mesopotamia, Part 4

Written Law Codes

Today most countries have written legal codes and they have become the norm. But this was not the case in a larger civilisational context. Egypt did not have a written law code as we shall see in the next article. Mesopotamia was the first civilization to come up with an explicitly written code of law. There are so many famous law codes instituted by various rulers - for example: Ur-Namma [2100 BCE] and Lipit Eshtar 1870 BCE, Dadusha [1800 BCE] and Hammurabi 1750 BCE. There are also fragments of other law codes. The most prominent among them is the code of Hammurabi because it is the most extant and best preserved. Even though it was Hammurabi himself who wrote his law code, he credited its authorship to the god Marduk, the patron god of the city of Babylon.

All these law codes have a general feature - they are retaliatory. Basically under this system of justice, what you do to someone is done back to you as justice - so it is a retaliatory law code. For example, some laws from Hammurabi read as follows:

196: If a man has destroyed the eye of a man of the gentleman class, they shall destroy his eye.

197: If a man breaks another man's bone, his bone shall be broken.

200: If a man knocks out the teeth of his equal, his teeth shall be knocked out.

This is the origin of the phrase “an eye for an eye, a tooth for a tooth, a hand for a hand, a foot for a foot” which made its way into the Hebrew Bible (1) and from there, to the Western civilization.

But if there is serious injury, you have to take life for life, an eye for an eye, a tooth for a tooth, a hand for a hand, a foot for a foot, a burn for a burn, a wound for a wound, a bruise for a bruise.

(Bible) Exodus 21:23-25

One fascinating area of comparative study is the extent to which Mesopotamian law codes have influenced the law codes of the Jewish Bible. These resemblances look uncanny and definitely there is an influence from the Mesopotamian legal tradition on the later Hebrew civilization. Some comparisons are given below:

One can expect that laws like do not murder or commit adultery are pretty universal principles and hence are expected to be the same across all cultures even without one influencing the other. But there are other specific laws that look arbitrary but are carried forward exactly from the Mesopotamian tradition to the Biblical tradition.

Eshnunna 53: If an ox gored another ox and caused its death, the owners of the oxen shall divide between them the sale value of the living ox and the carcass of the dead one.

Bible - Exodus 21:35 - If anyone’s ox injures someone else’s ox and it dies, the two parties are to sell the live one and divide both the money and the dead animal equally1 (2)

The epilogue of Hammurabi’s and other law codes end with prosperity for those who obey the law and curses for those who disobey (3). So does the Mosaic law in the book of Exodus in the Bible. There are entire books written on this subject of the relation between the Mesopotamian and Hebraic legal traditions (4). This is not surprising because Mesopotamian culture spread throughout the Middle East and influenced several other later civilizations. The Bible tells us that the ancestor of the Hebrew peoples - Abraham - is originally from the city of Ur in Mesopotamia. This mostly reflects a pre-historic memory of the Israelites in Mesopotamia. Also, the Jews were exiled to Babylon in the neo-Babylonian empire in the sixth century BCE.

For now, let us focus on where the fundamental “eye for eye” principle takes us. There are some laws that sound irrational and weird when viewed alone but are a logical consequence of taking the eye for eye principle to its extreme. For example, law 230 in Hammurabi states that if a house that a builder builds, collapses and kills the son of the owner, then the builder’s son will be put to death. One might ask what mistake did the son make - why is the son of the builder punished instead of the builder himself? But it is a casual consequence of the eye-for-eye principle between the builder and the owner of the house he built. If the owner is killed by the house falling, then the builder of the house is killed for retaliation. If the owner loses his son, then the son of the builder is killed so that the builder experiences the same fate as the owner. This causal chain is evident in the way and the sequence in which the law is stated (5).

Hammurabi 229: If a builder builds a house for some one, and does not construct it properly, and the house which he built falls in and kills its owner, then that builder shall be put to death.

Hammurabi 230: If it kills the son of the owner the son of that builder shall be put to death.

Hammurabi 231: If it kills a slave of the owner, then he shall pay slave for slave to the owner of the house.

Hammurabi 232: If it ruins goods, he shall make compensation for all that has been ruined, and in as much as he did not construct properly this house which he built and it fell, he shall re-erect the house from his own means.

At some times, the law seems just by modern standards but in other cases, it seems unequal (the punishment for harming a slave or a woman is lesser than that of harming a free man) and at some instances, barbaric with the eye-for-eye principle.

But we also have lots of documentations of legal cases surviving from Mesopotamian archaeology and we do not find any references to them being actually quoted or used. Also, the actual outcomes of these cases do not match with the prescription of the law codes. So what role did these law codes exactly play? Were they mere ideals or imaginations of kings? This topic is debated among scholarly circles of Mesopotamian history.

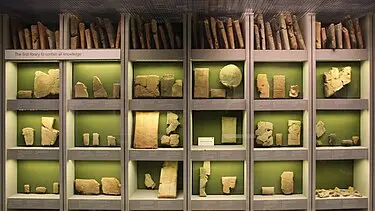

Ashurbanipal's Library gives modern historians information regarding people of the ancient Near East. In his Outline of History, H. G. Wells calls the library the most precious source of historical material in the world.

The Notion of a “Covenant”

Now, we will study a very important aspect of life in the Ancient Near East that has huge implications for the biblical tradition (6). It is the notion of the covenant. A covenant is basically a legally binding agreement signed between two parties who are unequal - an overlord and a vassal. It is to be understood in a feudal context - the overlord agrees to grant protection to the vassal if he submits to him and to punish the vassal if he disobeys him - and the covenant agreement contains the details of what the vassal and overlord are expected to do. Covenants are widely attested in the Mesopotamian archaeological record from about 2500 BCE onwards. Even the later Hittite Empire used the Mesopotamian Covenant model in all its treaties between the ruler and his subjects. A typical covenant consists of six parts.

- Preamble- the part where the overlord defines himself and gives his titles.

- Historical prologue - where the overlord defines his previous achievements and hence why he is capable.

- Stipulations - this part contains the DOs and DON’Ts of both the parties.

- Deposition - this part tells when and how the text of the treaty is to be displayed periodically for the constant reminder of it.

- Witnesses - this part contains the witnesses (typically gods who act as divine witnesses) on whom the covenant is sworn.

-

Blessings & Curses - Finally there is a list of rewards for obedience to the covenant and curses for disobedience to the covenant.

An integral part of all such covenants is the stipulation the vassal show loyalty exclusively, only to the lord and avoid submitting to other overlords who are out there. That is, the overlord expects that his vassals align only to him in this covenantal framework.

What happens very strangely in the Jewish tradition is that the Israelites model the relationship between their national god (Yahweh, the God of the Bible) and themselves as a covenant relationship where the Israelites see themselves as the vassals and their God is the overlord. The Israelites are described in the Bible as “bene ha-berit (Hebrew: Children of the Covenant)”. The word “covenant” in Latin becomes “testamentum” from which we get the phrases “Old Testament” and “New Testament”. All the six parts of the covenant are attested in the Bible.

- Preamble - “I am Yahweh, your God…” - Exodus 20:2a. Here God is introducing himself.

-

Historical prologue - “...who brought you out of the land of Egypt, out of the house of bondage” - Exodus 20:2b. Here, God is saying his achievement - that he has brought the Israelites out of slavery in Egypt and hence he is establishing this covenant with the Israelites.

- Stipulations - The books of Exodus from Chapter 20 and that of Leviticus and Deuteronomy are full of stipulations that the Israelites have to keep which include the famous ten commandments, the kosher dietary regulations and keeping the sabbath and so on.

-

Depositions - “At the end of every seven years, in the year for canceling debts, during the Festival of Tabernacles, when all Israel comes to appear before the Lord your God at the place he will choose, you shall read this law before them in their hearing. Assemble the people—men, women and children, and the foreigners residing in your towns — so they can listen and learn to fear the Lord your God and follow carefully all the words of this law. Their children, who do not know this law, must hear it and learn to fear the Lord your God as long as you live in the land you are crossing the Jordan to possess.” - Deuteronomy 31:9-13. This is an example of a covenant reading ceremony where the text of the covenant is read out loud to all the Israelites to remind them of the covenantal relationship.

-

Witnesses - As said before, usually the witnesses are the gods of the co-signatories. Given Israel’s lack of other gods, the Bible improvises: Josh. 24:22 has the people function as both signatories and witnesses. Sometimes natural phenomena are also used as witnesses. Eg. “And Joshua … took a great stone, and set it up under the oak in the sanctuary of the Lord. And Joshua said to all the people: ‘Behold! This stone shall be a witness against us, for it has heard all the words of the Lord which he spoke to us.” - Joshua 24:27.

-

Blessings & Curses - Finally, the end of the book of Deuteronomy is full of blessings and curses. For example - “If you obey the voice of the Lord your God, being careful to do all the commandments … blessed will you be in the city and blessed will you be in the field.” - a blessing in Deuteronomy 28:1. For an example of a curse - “If you do not obey the voice of the Lord your God or be careful to do all his commandments … cursed shall you be in the city, and cursed shall you be in the ¿eld … in all that you undertake to do, until you are destroyed and perish quickly … The Lord will smite you with the boils of Egypt, and with the ulcers, and the scurvy, and the itch of which you cannot be healed…” - Deuteronomy 28:15.

I mentioned that an integral part of covenant is exclusive obedience - a vassal can allege himself only to one overlord and will be punished by him if he obeys himself to another overlord. Since the Israelites saw the relationship between themselves and their national god as a covenant - this means that the Israelites are not allowed to worship other gods. This is made explicit in the first of the ten commandments - “You shall have no other gods before me; you shall not make for yourself a graven image, or any likeness of anything that is in heaven above, or that is in the earth beneath, or that is in the water under the earth; you shall not bow down to them or serve them.” - Exodus 20:3-6. Note here that God does not say that there are no other gods; it is implied that other gods exist to whom people can worship - but the Israelites are supposed to worship only the God to whom they have a covenant with - Yahweh. This is not monotheism (one god only exists) but monolatry (worship of one god while acknowledging the existence of other gods). So, ancient Israelite religion was not monotheistic - it became monotheistic only later in the age of prophets about which we will study in detail when we discuss Jewish civilization exclusively. You might ask - why did the Israelites model the relationship with the divine as a covenant when no other peoples around them did. This will also be seen in detail when we discuss Jewish civilization. So, Judaism sees its entire history in the covenantal framework - Israel suffers or prospers depending on its commitment to keeping the covenant.

Lessons For Us

What lessons can we learn for us and how will this information help us in our intellectual fight for our dharma? I give some of them below but think yourself too:

-

Two language families but one civilization: Next time when a proponent of the Dravidian movement argues that since Indo-Aryan and Dravidian are two completely distinct unrelated language families and hence cannot be a part of a single civilization, tell them about this Mesopotamian example where in two language families co-existed with each one having its own role and their two cultures merging into one and with each language being the mirror of the other, in expressing the common civilizational language! We will see more such examples later in other civilizations but Mesopotamia is an amazing example with lots of documented sources to work with. Although Egypt, China and Greece were linguistically homogeneous, these are not the only models of civilization. Cultural and linguistic boundaries need not coincide with civilizational boundaries.

-

Writing vs Speech: The primacy given to the written word in Mesopotamian civilization should give a good contrast to the primacy given to the spoken word in Indian civilization. One sees how Sumerian got studied and perfected and took over the role that Sanskrit played in Indian civilization but one sees that they achieve it differently - writing vs speaking. How this affects their philosophy of language is also a nice question to think about.

- Comparative Law & Comparative History: Another exercise one can take up is comprehensive study of legal systems. We as a civilization have faced constant criticism of our legal texts like Manusmṛti. It is highly essential for us to undertake a comparative study of various legal systems of various world civilizations to demonstrate how the Indian laws and the conducts of Indian kings are more humane. The horrific massacre that ensued when the Assyrian king Ashurbanipal conquered various territories for the resurgent Assyrian empire and punished rebels, finds no parallel in India. The eye-for-eye principle in Mesopotamian law which reflects in the Biblical law code is important to know of. It does indeed reflect a mindset of revenge. Also, studying Mesopotamian law codes is important in tandem with the Bible which will tell us how much the Biblical material owes to its Mesopotamian predecessors and in what all aspects it has innovated.

-

Similarities: A comprehensive comparative study of all civilizations has shown me how the two Abrahamic evangelizing faiths are of an entirely different nature from the rest of the ancient civilizationally rooted faiths. In the present global world, a polytheistic, idol-worshiping, nature-worshiping, ancestor-worshiping Hindu like us are the minority and the outliers in a geopolitics dominated by Christianity and Islam. Hindu apologists have always defended and continued to defend their faith by trying to make Hinduism look like a monotheistic faith or to mold it into a monotheistic faith but it is high time we stop being apologetic. By studying ancient civilizations, one gets how 2000 years ago, most of the world was indeed like us and there is nothing unusual or inferior about idol worship or believing in myths or having a philosophy and worldview in harmony with one’s religions and traditions. It is the Christians and Muslims who are unusual as they defy these ancient orders to build something new and they have made the only surviving ancient civilization (Hindu civilization) look abnormal as they have successfully managed to destroy all other civilizations or atleast sever their connection to their past through Christianity or Islam or Communism.

References

- Exodus 21:23-27

- Exodus 21:35

- The Code of Hammurabi

- David P Wright, “Inventing God’s Law: How the Covenant Code of the Bible used and revised the laws of Hammurabi” , Oxford University Press, 2009

- The Code of Hammurabi

- Biblical Covenants in Their Ancient Near Eastern Context