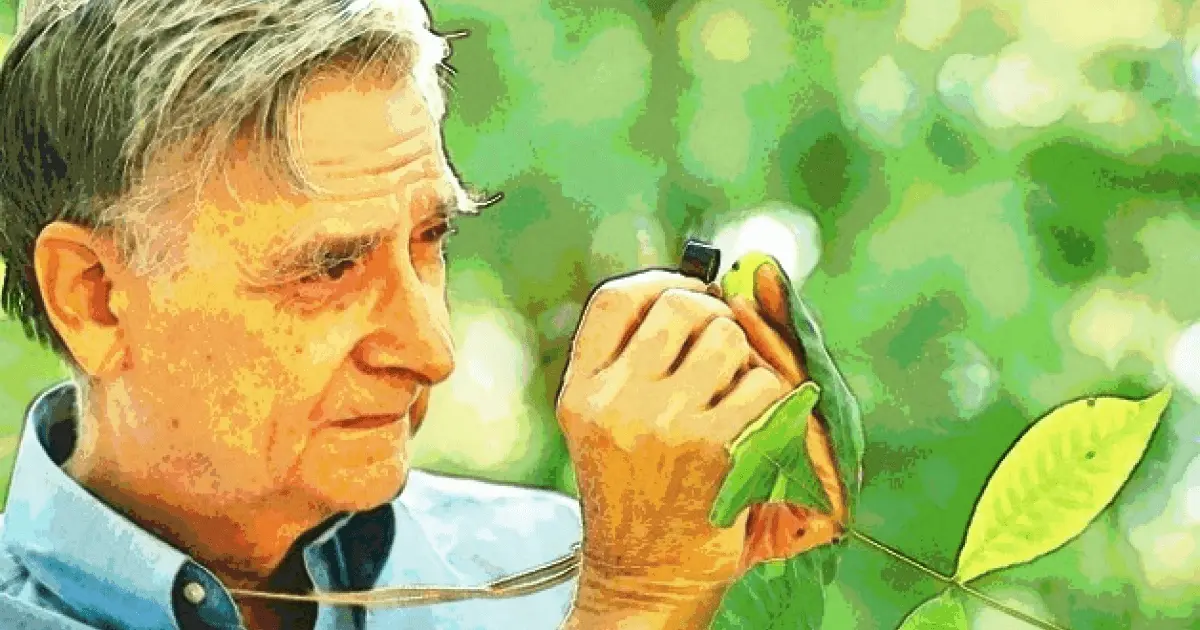

When a big tree falls, the ground trembles. But when a leaf gently kisses the ground at the end of its life, it nourishes it for future biota. Last year on this day, one of Earth’s most devoted sons touched her feet and bid her farewell, leaving behind profound wisdom for generations to follow. This dedicated son was the gifted naturalist Edward Osborne Wilson.

Most readers of this article would be ensconced between four walls, surrounded by buildings, roads and the occasional trees. Apart from some fortunate ones who may be tucked in the lap of nature, many of us lose sight of life and what it means to sustain it. Wilson, though blind in one eye, saw nature at a depth ungraspable to a mind deluged in artificiality. From insects to humans, economy to ecology and from Man to God, he had a scientific take on many subjects which deserve to be read.

A remarkable proponent of biodiversity preservation, Wilson in his book, The Future of Life, presents a mock debate between an economist and an ecologist. With the preface that both are well-intentioned and that preservation of human life is a common goal for both, the economist points to the increasing quality of life globally, the spectacular growth in GDP and democracy in many countries, and the benefits of modern medicine. He expounds on the progress made by us and assures us that the human genius which has kept the Malthusian doomsday prediction of resource crunch at bay for 200 years, will continue to do so well into the future.

The ecologist argues that improving science can only postpone the impending disaster but not allay it. We have already entered dangerous territory and as the resource requirement grows, the pressure on land will become irresistible to the detriment of humans and worse, to much of the rest of life. Like the whaling industry which nearly drove whales to extinction, wanton industrialisation will turn into a sudden catastrophe risking the entire biosphere. Moreover, the development model which does not take into account the loss of natural environment and biodiversity is flawed, fundamentally.

Acountry that levels its forests, drains its aquifers, and washes its topsoil down river without measuring the cost is a country travelling blind.1 This is a compelling debate that no thinking person can discount. No one can deny the benefits of technology, nor can the prevalence of widespread poverty in society be overlooked. However, the alarming rate of extinction and shrinking of natural habitats is also a fact, a reality which will come to haunt us later if we do not pay heed to it.

A critical point which passes under the radar in this discussion is the subtle anthropocentrism being pushed through the present consumption model. Science shows that humans are just one among millions of species, and evolved through primates. Humans have become a geophysical force, capable of altering environments to our needs. However, hacking at the tree of life for short-term gain, while ourselves sitting on the branch, is not only selfish but thoroughly irrational as well. Wilson suggests utilizing science to bring about behavioural change.

What better way to teach science than to present it as a friend of life rather than as an uncontrolled destructive force?2

Our own worldview as Hindus promotes this way of thinking. Resource crunch or not, our society has always prized austerity and inter-specieal camaraderie. It has sought to be guided by Brahmavādins, whose carya demands them to put on the maximum amount of restrictions on self. But we too have strayed from the path.

More than anything else, the importance of biodiversity is reinforced by its description, and here is where Wilson’s works truly shine. His expositions in The Diversity of Life and The Future of Life create a beautiful picture of the web of life surrounding Earth, and the delicate balance that it treads. It not only informs us about the world around us (one vanishing rapidly), but it also informs us about ourselves (perception of which too is changing rapidly).

Humanity progressed exponentially beyond other species due to a trait called Eusociality. Eusociality is the ability to form group relations and have altruistic tendencies towards members of the group, along with the division of labour. More than our individual intelligence, it is this ability to pool and retain knowledge that gave us our edge. In this quality, humans are akin to other social insects like ants, bees, termites etc, a point not lost on the author who remarks on the precariously growing population in his typical sarcasm:

The pattern of human population growth in the 20th century was more bacterial than primate.3

But our nature is not that of any other species. During the 20th century, there was an intense debate on whether human nature was shaped entirely by our underlying genes, or whether they were part of our God-endowed culture (creationist argument). Nature vs Nurture. According to Wilson, the answer lay in between and thus was born the discipline of epigenetics.

Epigenetics forms a basic set of consciously controllable rules, evolved by the interaction of genetics and cultural elements. They are the genetic biases as per which our senses perceive the world, more consciously controllable than reflexes but baser than culture. They initiate ‘prepared learning’ (predisposed preferences) within us. A few examples may be lactose tolerance, incest avoidance and colour coding by various cultures around the world. These examples prove that human nature is not arbitrarily dependent on genes, but is an amalgam of cultural elements as well.

These rules have defined the pattern of human evolution. The formation of groups, morals, art and religion have been attributed by the author to these rules. It was observed that the cooperation capability of humans led us to achieve material dominance as a species, whereas selfish traits led to personal glory.

Nevertheless, an iron rule exists in genetic social evolution. It is that selfish individuals beat altruistic individuals, while groups of altruists beat groups of selfish individuals.4

Advancing from material planes, Wilson also wrote on the evolution of religion, a topic which most sociologists avoid, unfortunately. Being an agnostic, the author is pretty plain towards organised religions and the claims of experiencing divinity through herbs or self-inflicted harm. However, a point which becomes conspicuous by its absence is his ignorance of Indian traditions (a trait shared by many other great western social scientists as well, such as Jared Diamond). Sages since yore (non-Abrahamic) have defined human nature to be divine. Ram Swarup ji had defined human nature to be constituted of physical, mental and spiritual elements. This knowledge is critical to be more widely understood and disseminated. It may be thus providence asking Hindus to take up social sciences genuinely, to build a bridge between Western and Eastern understanding of Man and God.

Despite shortcomings, E.O. Wilson was a truly great humanist person with a deep affection towards nature. This affection must be sought to be cultivated by each human being, who must come together and seek to build points of convergence instead of tribalistic differences. Towards that end, the author had laid out an educational blueprint as well, without which this piece would be incomplete.

If Homo Sapiens as a whole must have a creation myth, and emotionally in the age of globalization it seems we must, none is more solid and unifying for the species than evolutionary history.5

Endnotes:

- Wilson, Edward O. (2002). The future of life. New York : Alfred A. Knopf (pg 26)

- Ibid. (Pg 188)

- Ibid (Pg 29)

- Wilson, E. O. (2012). The social conquest of Earth. W W Norton & Co. (Pg 243)

- Wilson, Edward O. (2002). The future of life. New York : Alfred A. Knopf (Pg 133)