Can capitalism, with its materialistic and profit-driven motives, coexist with or be reformed by dharma's ethical and spiritual imperatives? Also, how does dharma provide a counter-narrative to the cultural dominance of capitalism?

The world stands on the brink of the fourth industrial revolution, and India has firmly emerged as a key player in the global capital market, rapidly having readily embraced corporatization and liberalization. In the West, however, inflation, wealth inequality and ideological battles seem to be at the forefront, with the effects of late stage or ‘multinational’ capitalism playing out. While there is optimism that India is better equipped than the West to straddle both modernity and tradition with its roots intact, this cannot be accompanied by inaction.

The idea of development is important insofar as it directly affects policy decisions. For India, it should not be vague and indeterminate, and unless conscious decisions are taken to ascertain the exact type and form of development that our country would benefit from, the wrong policy choices would lead to a reversion to the default — the exploitative colonial version. Therefore we must ask ourselves, whether we are fated to economic determinism or do we retain some agency in determining the trajectory of Bhārata henceforth. As Daniel Bell poses the question in Cultural Contradictions of Capitalism-

If one loses the anchorages of tradition and religion, what will be left of economic power and cultural syncretism for these new civilizations, if not some further contradictions of capitalism?

In order to consciously resist descension into the pernicious cultural and religious consequences that a hyper-capitalistic trajectory creates, it is imperative that we pay attention to and carefully steer this inevitable force of ‘development’. To this end, a rethinking of our economic policy, and a return to IKS (Indian Knowledge Systems)-based thought is a necessary intervention to stay true to Bhārata’s ancient wisdom. In this piece, we make a case for dhārmika capitalism, which incorporates ethical and moral principles like welfarism and social security into policy and the economic model, which entails an embedding of dharma into all spheres of governance: law, policy and especially, the regulation of capitalism.

A Brief History of Capitalism

The advent of globalization, deregulation and privatization in the 80s and 90s promised growth impervious to inflation, with the rise of technology and global integration creating a continuous supply boom, while emerging markets served as a source of cheap labour. Capitalism is seen as a new breed of American imperialism, a contemporary reincarnation of what started as colonial imperialism. In the current setup, it involves overaccumulation of capital through dispossession, and through superficially operating through a “peaceful” and “open” market, it relies on power — through techniques such as creative destruction, stock market manipulation, lobbying, exploitation of labour, creating debt crises, the commodification of natural resources, and military conquest. The material essence of capital on the one hand and the processes of power on the other are seen as embedded in its very framework. Rosa Luxemburg, a Marxist revolutionist against capitalism, wrote-

Capitalism, by mightily furthering the development of the productive forces, and in virtue of its inherent contradictions,...provide(s) an excellent soil for the historical progress of society towards new economic and social forms.’ In this way, capitalism is a totalising force, embodying the Western political and hegemonic ideas of “progress” and “development.”

Postmodernist thought has also described the deleterious effects of late stage capitalism or ‘spectacle capitalism’ as explained by Jameson: the mediatization of culture, American military dominance alongside the changing nature of wars, business organisation consisting of all-powerful multinationals — beyond monopolies and oligopolies, the emergence of banking and financial structures wherein the first world’s elites and corporations maintain control over the world market, automation, hyperconsumerism juxtaposed with the planned obsolescence of goods, etc.

The Relationship between Markets and Society

Well-being, more loosely connected with markets, is less likely to be affected-positively or negatively — by how markets develop, expand, or are contaminated or purified. Certainly, how well-being is affected depends on how, when the dust settles, the boundaries between market and society have been redrawn.

Dolfsma, et. al., Market and Society: How Do They Relate, and How Do They Contribute to Welfare?

The relationship between business and society is hotly debated in the social sciences, with thinkers such as Hobbes, Smith and Hume attempting to theorize upon it. The contribution of the markets to economic well-being is undeniable, and so is their mutual interdependence. Business has a stake in and directly affects the pillars of a society (Robert P. George, in Are Markets Moral? describes the five pillars of a decent and dynamic society as being business and education, together with respect for the dignity of a human being, the institution of the family, and the system of law and government).

Therefore, society has a stake in what goes on in business, and business in turn has a large stake in what goes on in broader society — not only because societal developments directly affect business, but also because they indirectly influence policy. “Business, in important ways, depends for its flourishing on things that business itself cannot produce” (Melzer, 2018). Moreover, context-specific socio-cultural values often underlie that of any market’s, despite to a limited extent. Wherever business operates, it does so in the context of a larger society. It is affected by what happens in various other dimensions of the society, and it in turn affects them. Increasingly in the capitalistic age, society merely exists as a backdrop for corporations, helpful only to the extent of tailoring marketing and advertising to a culture, language or people, or exploiting faultlines. Capitalism replaces societal fabric, trust and security by atomizing and fragmenting society, exalting the individual as a private actor over the family, community, society, or ecology. As Byung-Chul Han states in The Disappearance of Rituals: A Topology of the Present:

Capitalism is often interpreted as a religion. However, if religion is understood in terms of religare, as something that binds, then capitalism is anything but a religion because it lacks any force to assemble, to create community. Money, by itself, has an individualizing and isolating effect. It increases my individual freedom by liberating me from any personal bond with others. I can have someone else work for me by paying her, and this avoids entering into a personal relationship.. Capitalism, by contrast, erases the distinction between the sacred and the profane by totalizing the profane. It makes everything comparable to everything else and thus equal to everything else.

Moral Objections to Capitalism

A society that has liberated and legitimated the human impulse for continuous gain tends to produce a materialistic culture that hinders people from hearing the call of their higher longings. To be sure, in a liberal capitalist society people remain nominally free to follow any way of life they choose, but in practice it is not so easy to escape the pervasive influence of one’s society and culture.

Arthur M. Melzer, essay in 'Are Markets Moral?'

Questioning the ‘march of progress’ hierarchical model that capitalism embodies, the notion of utility maximization as the only economic pursuit, and wealth creation for its own sake rather than towards any higher aims such as providing for family, society, etc. are all valid critiques of the future that we are hurtling towards. Arthur Melzer describes the “profit motive” that is characteristic of capitalism is distinct from a merely acquisitive outlook towards life — described as an “open-ended desire for material gain, the embrace of acquisitiveness more or less for its own sake, neither grounded in nor limited by some clear final end or purpose beyond it.” This is where Dharma comes in, specifically the orientation towards the puruṣārthas that it brings. Paradoxically, capitalism is also alarming for seeking to also providing an antidote to the same shallow materialism that it proliferates, by “selling spirituality” (see Jeremy R Carrette’s work of the same name) i.e., monetizing aesthetic and spiritual pursuits and creating a global market for them.

Capitalism focuses on the historical process of the spread of capital, investment and growth, underscored by both destructive and creative forces, which transform economies. The limits of national economies provide a major impetus for the spread of capital in search of markets, cheap raw materials and labour, with profits underpinned by tensions between capital and labour galvanising the shifts. Moreover, contemporary globalization captures the intensification of the drive to create a “borderless world” fuelled by information and communication, ultimately aiding the creation of “emerging markets” out of developing nations.

The discussion of the effects of the hyper-commercialization and commodification mindset of capitalism is important because the manner in which a society has organised its production and consumption of material goods informs how the rest of that society operates. Capitalism is not merely a mode of production for the free market but also dictates the commodification of labour, with the workers only able to own the personal conditions of production without a share of the profit or method of production (a Marxist critique of capitalism).

Greenwashing

Giant corporations and industries are not only extractive of resources and labour, but also engage in toxic and polluting acts that directly and indirectly endanger human health. Amidst these growing environmental and health concerns, there has been an increasing prevalence of messaging by corporations that speaks to the environmentally conscious consumer by painting the company as being more “sustainable” and socially responsible, while in reality, it may not be so. American environmentalist Jay Westerveld used the term “greenwashing” to refer to “false environmental protection claims” of corporations and businesses after a trip to a resort in Fiji that requested their guests to reuse towels to save the reefs, while simply being a way to reduce laundry costs, and the company was otherwise engaged in environmentally destructive construction work elsewhere on the island.

Greenwashing, therefore, in the context of corporate messaging or advertising refers to misleading or posturing behaviour in order to appear environmentally conscious or responsible in public imagery. It blends the terms “green” and “whitewash” to indicate a deliberate malpresentation, false claims, selective disclosure or omission, and/or projection of environmental consciousness in the face of the contrary. This phenomenon arose because market trends indicate that consumers are willing to pay more for environmentally friendly products, though the actual product does not always do justice to the claims and marketing. Given the urgency of the global environmental problem, and the requirement to curb unidimensional, profiteering tendency of the capitalist corporate regime, greenwashing, if unregulated and allowed to continue unchecked, might lead to more masquerading practices rather than the driving of investment and research towards true sustainability. However, long-term, holistic solutions can only be formulated and enforced through society-driven yet state-mandated strengthening of corporate responsibility to the environment as the world becomes increasingly dominated by and even frustratingly, economically beholden to the corporate world.

The Metaphysics of Capitalism

Weber in The Religion of India (p. 112) blames the influence of Hinduism and the caste system for inhibiting economic development comparable to that of modern European capitalism. ‘A ritual law,’ Weber remarks, ‘in which every change of occupation, every change in work technique, may result in ritual degradation is certainly not capable of giving birth to economic and technical revolutions from within itself…’

Capitalism operates below the level of the state and above the level of society, and therefore cannot provide a general theory of society, or create aspirations to any higher ideals than simply the accumulation of capital. At its heart, however, capitalism embodies the desires and beliefs of the ruling capitalist class, and their worldview is imposed on the rest of society. This is all the more clear when tracing the history of the origin of capitalism in Europe to merchant guilds and colonial, imperial corporations and/or nations, and analysing the mechanics — or rather machinations — of the frameworks of international trade and global financial markets.

The aforementioned lacuna for the theory of state and society, was previously occupied by Dharma before the imposition of “secular” positive law by colonial forces. In the 18th and 19th centuries, the world adopted a system of law known as positive law, whose central feature was that it was secularized, and did not incorporate morality: thus divorcing law from morality. The resultant effect therefore, was the marginalization of a religion and the code of ethics that was inherent to it. Law and morality do not develop independently, and reflect the society from which they emerge. Positivism, by being devoid of metaphysics and any contextualization, neglects the qualities of the individual (or the nation-state in the case of international law) expected to follow the law, in order to further the agenda of universalization of the law. Capitalism, as imperialism, requires countries to subscribe to largely the same legal and institutional structure in order to trade and engage in business, resulting in a universalizing, subsumptive imposition of the global world order.

It is predicated on the idea of equality (or sovereignty in the case of international law) in order to have universal applicability, and therefore is seen as “just”. Dharma, on the other hand, does not envision a law devoid of morality and metaphysics, and provides a highly individualized, localized view of what the law ought to be and achieve; dharma provides prescriptions based on lived traditions, and expectations based on the nature of the subject of law. Contrary to the precepts of modern business law, the Dharmaśāstras believe that morality can be legislated, and saw no need to draw sharp distinctions between legal and moral prescriptions. Ancient legal systems recognise the need to advance the collective society’s moral vision and ideals, and the law represents a tangible, worldly way to do so.

Critics of positivism maintain that law must embody metaphysical principles and not merely serve political ends, if it is to seek to ‘maximize the conditions under which each individual or group of individuals can realise themselves and attain their moral ends’ (Singh, 1985). This brings us to the question of whether the modern effort to separate legal and moral questions is a potentially dangerous one. We can still remain sympathetic to the positivist and realist views of law which state that the law must be applied regardless of moral content, however, in the framing of laws, a consideration to promote moral ideals would not hurt. Dharma presents such a metaphysics for the presence of law and regulatory codes in society, and also exists as a worldview in itself, creating a code of moral, ethical actions for maximizing individual well-being. Ethics is required if we are to address the challenges of sustainable growth, inequality, climate change, corruption etc. rather than further entrenching existing socio-legal mentalities which are grossly inadequate.

Business as Dharma

The Dharmaśāstras state that the king, as an integral part of his kṣatrīya dharma, has a vested interest in having a knowledge of and regulating the economic landscape, for the welfare of his people. The dharma of business or occupation is called vrata/vṛtta dharma, as opposed to sāmānya dharma applicable broadly to all. The vyavahāra kāṇḍa (portion containing substantive and procedural laws) of the Dharmaśāstra can be seen as substantive laws for business, and include basic rules for interest, contracts, deposits, sales, loans and other fiduciary transactions. Property is dealt with as part of inheritance laws. Breaking these rules was not just illegal, it was immoral, a sin, and conducting business transactions according to these rules resulted in the accrual of good karma. It was the role of the state to intervene only in case of civil and criminal violations, for example, to determine compensation for loss of business property, and in the case of emergencies such as famine, drought and natural disasters (apad-dharma). Apart from containing the rules of statecraft and kingship, which include the regulation and maintenance of the economy, the Arthaśāstra also emphasised production and productivity.

Business was a legitimate and valued enterprise associated with the religiously defined social class of vaiśyas, to whom business and business law formed the core of dharma. For everyone else, recognizing the inability to lead a respectable life without artha, business and wealth are also central to dharma, elevated as one of the four main aims of life, the puruṣārthas. Occupation and religious duty are linked, but the materialist ends of commerce were never elevated above the status they were meant to occupy. The socio-religious world is prioritized over the economic domain. This is important because in trade/business, when the generation of wealth, artha, is considered dharma in itself, it is automatically implied that there are strict moral codes and ethics that govern the conduct of business. “Secular” rules are placed within the religious context. While lābha or profit is emphasized and desirable, lobha, or greed is shunned. This is in direct contradiction with the manner in which modern capitalist markets work, with companies only guided by the primary aim of grotesquely increasing profit for shareholders year after year through resorting to unjust and exploitative means, affecting both human and environment. As Donald Davis Jr. remarks, “labelling of obviously worldly, business-related transactions as dharma draws a big semantic circle around seemingly disparate domains as the religious rites of households, the responsibilities of a king, and the transactions of business and trade.” In other words, every action was sacralized, and given a higher purpose and meaning, in order to better situate the individual member of society to pursue and attain his puruṣārthas, the ultimate goal being mokṣa. Donald Davis, Jr. in ‘The Dharma of Business’ writes:

First, business is tied to and mutually influences religion, politics, and community, and it cannot be treated as an independent institution. Second, where there is conflict, business concerns and goals must yield to religious, social, and political goals. Lastly, business without virtue is exploitation and theft, and should be treated accordingly.

The Dharmaśāstras also lay out a law of partnerships, where ‘relationships are personalised and set in a framework of mutual trust and expectation’, ‘penalizing breaches of trust severely’ and ‘emphasiz(ing) the risks of depersonalising business’ (Davis Jr., 2017). They predicate that business is ‘impossible without the cultivation of personal relationships’, and that ‘social interactions prefigure economic wellbeing or insecurity’ (Davis Jr., 2017).

This is akin to embodying ethical principles of a theory known as ‘ethics of care’ — also called relational ethics, centred on bonds and interpersonal relationships — as opposed to consequentialist or utilitarian ethics. In contrast, depersonalization, by minimizing human relationship-building and limiting personal interaction are central features of the modern corporate workplace, guised as ‘professionalism’ and ‘corporate etiquette’. Breaches of trust and contract and litigiousness are commonplace despite the legal ramifications in a hyper-competitive, aggressive market. In other words, the modern world is fixated on elevating the economic over the social, to the detriment of social and interpersonal relationships.

Rethinking Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR)

In the 21st century we can all agree to disagree with Milton Friedman’s famous statement that the “one and only one social responsibility of business — to use its resources and engage in activities designed to increase its profits”, and extend the responsibility of corporations to the society and the environment at large. The original intent and logic of instituting CSR remains valid, and in fact, calls for corporations to give more back to society that they extract from to geometrically multiply their wealth, are growing louder. The European Convention on Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) defines CSR as *a concept whereby companies integrate social and environmental concerns in their business operations and in their interaction with their stakeholders on a voluntary basis*.

The Dharmaśāstras also envisioned holding businesses accountable, not just for their moral actions and behaviour but for giving back to society through charity. Dāna is encoded within dharma, and is seen as being an integral part of social life — everyone is engaged in some giving and receiving, based on their own ability and the responsibility assigned to them. For instance, during a time of peak economic prosperity in medieval era Tamil Nadu, merchant guilds often sponsored the construction of massive temples and public infrastructure in their respective regions — undertaking projects that even the state may not have the spare funds or inclination for. Things have changed substantially. Some global multinational corporations have more wealth than whole nations, and far more reach and power. This sort of power must be regulated to the benefit of society as a whole, not used to further drive unchecked environmental extraction and wealth inequality. To this end, CSR is an inadequate construct to adequately enforce public and social responsibility that corporations ought to have, and must be rethought to better reflect a society’s ultimate aims.

Orienting Policy to Incorporate Dharma

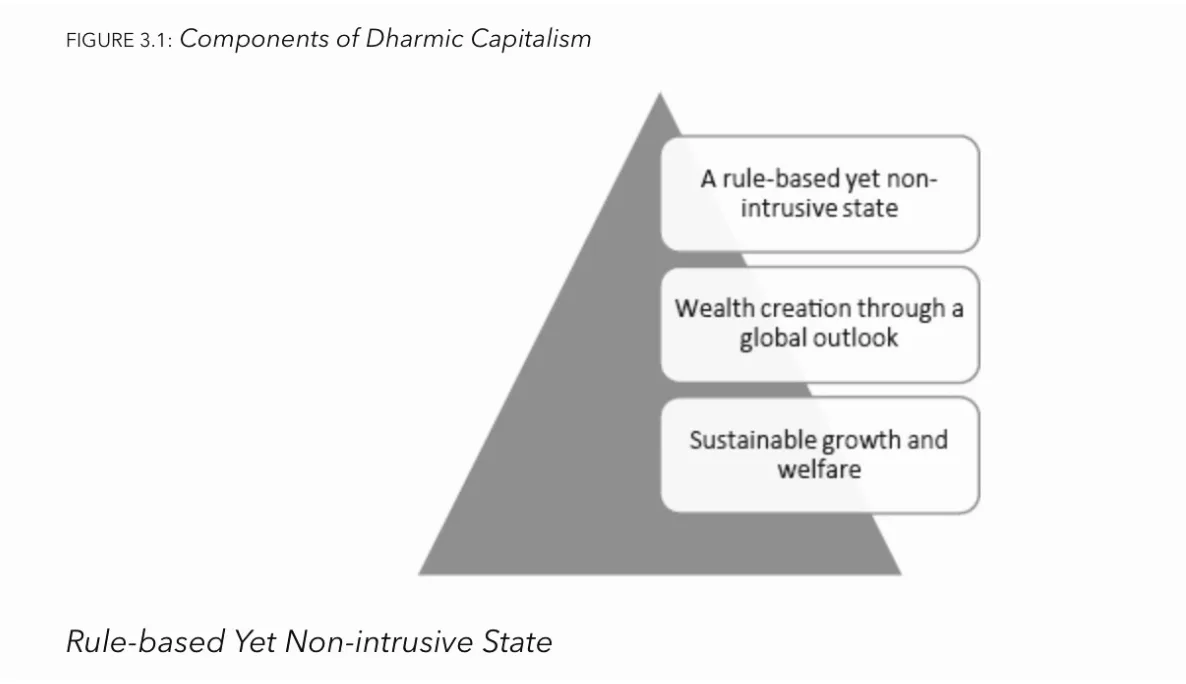

S. Balasubramanian in ‘Kautilyanomics’ suggests the model of the Kautilyan dharmic state is society-centric, neither laissez-faire nor Keynesian (see note 1), based in ethical precepts grounded in dharma. Crystallizing our own idea of development is important because it influences policy and the processes of coming to such policy decisions. Right now, India has unquestioningly adopted the top down, elitist, GDP-driven idea of growth rather than embracing individual and social capability and greater economic freedom. The aim of pursuing a dharma-based idea of economic growth would be to equip the individual and the economic units of society (such as merchant classes) with the necessary factors to allow for pursuing their own interests. Therefore, a rule-based, yet non-intrusive state that is based on the pillars of wealth creation through both domestic and global trade, and yet promoting sustainable consumption and development, welfarism and social security. The diagram below is from his work, depicting the three-pillared view of dharma-based capitalism.

Source: ‘Kautilyanomics’, Balasubramanian, Sriram.

Source: ‘Kautilyanomics’, Balasubramanian, Sriram.

Donald Davis, Jr. in ‘The Dharma of Business’ writes that “Business is predicated on efficiency, predictability, and profit, among other things, and Dharmashastra certainly recognizes these aims as legitimate and attempts to safeguard them legally. At the same time, these values are not absolute or superior to other values equally protected under the law.” The purpose of undertaking this entire discussion has been to make the case for a tighter regulation of capitalism, and its reform, through the gradual incorporation of dharmic principles. After all, it has been established that capitalism carries with it the interests of the global corporate elite rather than reflecting the values and interests of the society it might be based in. And if we are to get a word in as the world escapes into the future down an intractable path, the time to be confronted with all of these uncomfortable questions is now.

Endnotes and References

Note 1: The perspective underlying the Keynesian welfare state views the market as part of and regulated according to dominant social or societal values such as norms of distributive justice. The process of liberalization and privatization (reform) boils down to an attenuated role for the state, certainly in terms of distributive justice, and there is a shift in values toward those centering on the individual and toward negative freedom. The state is viewed in such a perspective as a force of coercion, whereas the market is viewed as the domain of freedom. Taken from: Dolfsma, Wilfred, John Finch, and Robert McMaster. “Market and Society: How Do They Relate, and How Do They Contribute to Welfare?” Journal of Economic Issues 39, no. 2 (2005): 347–56.

- Nitzan, Jonathan, and Shimshon Bichler. “New Imperialism or New Capitalism?” Review (Fernand Braudel Center) 29, no. 1 (2006): 1–86.

- Roy, Sumit. Review of Capitalism, Globalisation and Trade: Challenges, by Prem Shankar Jha, T K Bhaumik, Rajendra K Jain, and Hartmut Elsenhans. World Affairs: The Journal of International Issues 11, no. 1 (2007): 136–48.

- Donald, Jr. Davis R. The Dharma of Business: Commercial Law in Medieval India. India: Random House Publishers India Pvt. Limited, 2017.

- Are Markets Moral?. Germany, University of Pennsylvania Press, Incorporated, 2018.

- Melzer, Arthur M.. [1. The Moral Resistance to Capitalism: A Brief Overview](https://doi.org/10.9783/9780812295405-003). Are Markets Moral?, edited by Melzer, Arthur M. and Kautz, Steven J., Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2019, pp. 7-14

- George, Robert P.. [5. Five Pillars of Decent and Dynamic Societies](https://doi.org/10.9783/9780812295405-007). Are Markets Moral?, edited by Melzer, Arthur M. and Kautz, Steven J., Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2019, pp. 85-95.

- Balasubramanian, Sriram. Kautilyanomics: For Modern Times. India: Bloomsbury Publishing, 2022.

- Jameson, Fredric. Postmodernism, or, The Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism. Duke University Press, 1991.

- Law from Anarchy to Utopia: An Exposition of the Logical, Epistemological, and Ontological Foundations of the Idea of Law, by an Inquiry Into the Nature of Legal Propositions and the Basis of Legal Authority. Calwant Singh & Chhatrapati Singh - 1985 - Delhi: Oxford University Press USA.

- Carrette, J., & King, R. (2004). Selling Spirituality: The Silent Takeover of Religion (1st ed.). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203494875

- Dolfsma, Wilfred, John Finch, and Robert McMaster. “Market and Society: How Do They Relate, and How Do They Contribute to Welfare?” Journal of Economic Issues 39, no. 2 (2005): 347–56.

- Geras, N., 1973. Rosa Luxemburg: Barbarism and the Collapse of Capitalism. New Left Review, 82, pp.17-37.