At the entrance of a government-run emporium in central Delhi, a middle-aged woman with silver bangles on her wrist arranges a row of terracotta figurines. She has done this every morning for seventeen years, adjusting the posture of a dancing tribal woman, brushing dust from the painted elephant, shifting the bamboo flutes into alignment. Behind her, a board announces: “Tribal Art. Cultural Heritage. Proudly Preserved.”

Inside, shelves are neatly marked. Gond paintings from Madhya Pradesh, bamboo crafts from Nagaland, shawls from Kullu, silver jewellery from Bastar. The store is a cultural map of India, compressed into a catalog of price tags and craft clusters. It is also a metaphor for the way Indian public policy has long understood culture. Neat, knowable, administrable.

But step outside this curated space, and the picture changes. The Gond artist who created that painting might now be living in Bhopal, painting TikTok-style illustrations for Instagram commissions. The weaver from Nagaland might be studying fashion design in Delhi, refusing to weave anymore. The shawl marked “Kullu” might be made in Ludhiana. And the bangle seller? She jokes that no one buys bangles anymore. They buy stories.

There is a deeper disjuncture here; between the ways people live and the ways policy imagines their lives. Culture, in the eyes of the state, is still something fixed, something that must be protected or uplifted. But in the lives of citizens, culture is something made, unmade, and remade constantly. It is migratory, messy, and deeply political.

The Field Is Not Where You Think

This disjuncture has long been present in the disciplines of anthropology and sociology in India, where much of the intellectual scaffolding for policy formation has historically been laid. In Culture, Power, Place: Explorations in Critical Anthropology, editors Akhil Gupta and James Ferguson argue that the field of anthropology was built upon a problematic idea: that cultures are spatially bounded entities. The idea that you could go into the field to study a culture presupposed that people and their practices were contained within territory, tradition, and typology.

Gupta and Ferguson call this the “peoples and cultures” paradigm. It shaped how generations of anthropologists wrote about the world; “Hopi culture,” “Ndembu rituals,” “village India.” The anthropologist was the outsider entering a bounded inside. Fieldwork became a kind of safari.

But what happens when cultures are no longer contained? What happens when the village boy becomes a call center employee in Noida? When the refugee writes poetry on Instagram? When “local” becomes a performance, often demanded by NGO project reports or donor logics?

Gupta and Ferguson suggest that culture is not a pre-given object that exists in place, but a process produced through power. People do not simply inherit culture. They negotiate it, represent it, resist it. In their formulation, the field is not a place you go to. It is something you are always already inside. This shift, subtle yet seismic, invites us to rethink not just anthropology but the entire architecture of policy.

The Colonial Cartography of Culture

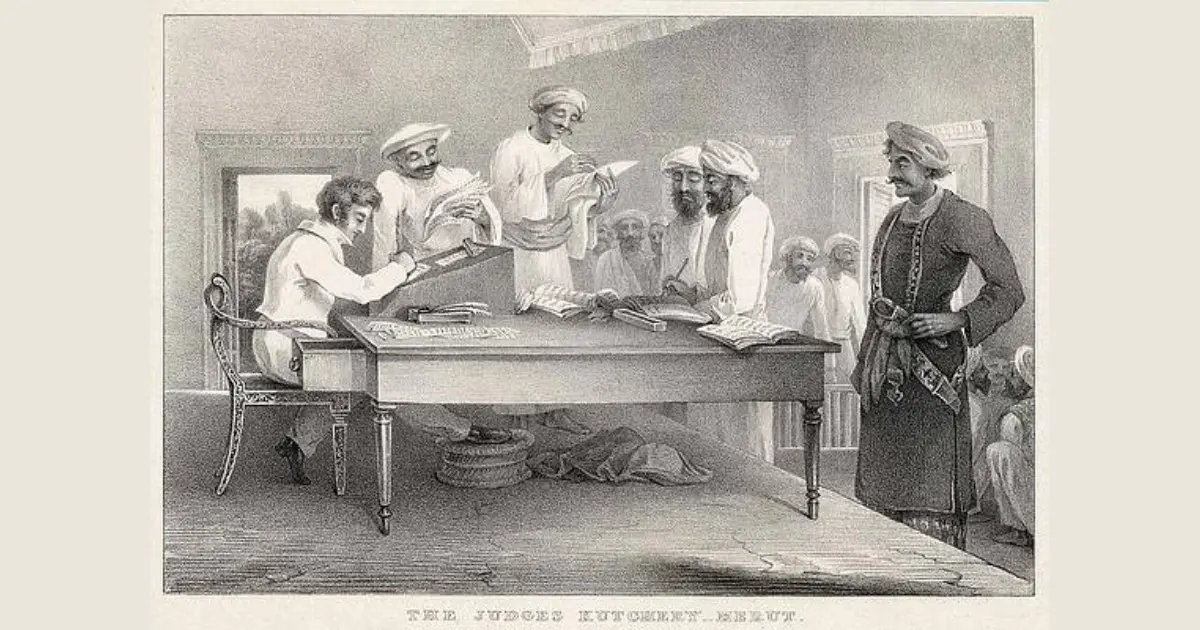

The Indian state has long used anthropology as a tool of classification. As Sudipta Kaviraj has argued, sociology in India did not emerge to understand society in all its complexity. It emerged to render society legible to the state. Colonial administrators needed to know which tribes could be taxed, which castes could be recruited into the army, which customs needed “reform.” Post-independence, this logic continued under a nationalist guise. Planners needed data, and anthropologists provided it.

The tribal welfare department, for instance, continues to operate on a model inherited from colonial times. To access benefits, you must belong to a Scheduled Tribe. But how do you prove this? A certificate issued by a block officer, based on documentary evidence or community verification. In one case I encountered in Jharkhand, a child was denied school admission because her grandmother had married outside the tribe. Her father, born into a tribal village, raised in a tribal household, and speaking the tribal language, could not get her the certificate. Culture, for the state, was not about lived reality. It was about bloodlines and boxes.

Ashis Nandy saw this tendency clearly. The Indian state, he wrote, speaks the language of rationality but acts through deeply-embedded social codes. It treats tradition as an obstacle and culture as a museum. It wants its citizens to be modern, but only in the ways that fit a bureaucratic imagination. When tribal communities are displaced by mining projects, they are compensated in monetary terms, even when their relationship to land is cosmological, sacred, and collective. When rural youth migrate to cities and blend Bhojpuri slang with Instagram reels, they are dismissed as “semi-literate” or “culturally uprooted,” rather than recognized as creators of a new idiom.

This blindness stems not from malice, but from a conceptual error: the belief that culture is fixed. That it exists in temples, festivals, or government emporiums. That it must be preserved, like a painting behind glass.

Technocratic Compassion and the State’s Unconscious

Partha Chatterjee offers an alternative frame. In his theory of political society, he argues that most Indians do not live in civil society; the realm of rational discourse, individual rights, and formal institutions. They live in a political society, where identities are negotiated, often tactically, and access to welfare depends on being seen as part of a group. In this space, culture is not an identity. It is a resource, a claim, sometimes a weapon.

I once met a group of women in western Odisha who had organized themselves into a collective to fight against a proposed dam project. They were all from different jātis and spoke different dialects, but they rallied around the language of ancestral land and sacred groves. When I asked them how long these groves had been considered sacred, one woman laughed and said, “Since the engineers came.”

This was not a lie. It was a strategy. A response to displacement, articulated in terms the state might understand. The women were not inventing culture. They were mobilizing it. They were shaping policy, even as it tried to shape them.

Culture, in this sense, is not content. It is practice. It is what people do to make meaning, assert dignity, and resist erasure. If we treat it as an object of governance, we miss its political vitality.

Toward a Culturally Intelligent Policy

A culturally intelligent policy would look different. It would recognize that categories like tribe, jātis, or region are not timeless truths but mutable constructs. It would treat culture not as essence but as expression. It would not ask “What are you?” but “What are you becoming?”

This shift has practical implications. For urban policy, it means acknowledging informal settlements not as failures of planning, but as cultural ecosystems. For health policy, it means engaging with indigenous healing not as superstition, but as epistemology. For environmental policy, it means respecting ritual knowledge not as folklore, but as a theory of human–nonhuman relations.

And for education, it means teaching students to think of culture not as a list of traditions, but as a way of reading the world.

Between the Bangle and the Bureaucrat

At the government emporium in Delhi, the bangle seller finishes her day by packing unsold items back into boxes. The labels are still intact. The story is still official. But outside, in the market, a younger woman is selling earrings made from soda cans. She says they are tribal too. Her friend posts photos online with captions like “Urban Jungle meets Forest Bling.”

No one asks for authenticity. They ask if it looks good.

The bureaucrat and the bangle seller live in different cultural worlds. Yet policy still imagines them as part of the same file.

Perhaps the first step toward better policy is not more data, but a different kind of listening. One that hears culture not as echo, but as voice.