Anirudh Kanisetti is back at it again with his nefarious agenda. In his most recent article for The Print, his hatred for Saṃskṛta and his giddy excitement at the chance to tarnish Hinduism is barely veiled (as usual). The premise of his article is that Saṃskṛta is glorified undeservingly, as it incubated a culture resistant to innovation: specifically, he claims that Saṃskṛta bred stagnation in the fields of mathematics and astronomy. Kanisetti begins by condescendingly stating that Saṃskṛta being a language suited to programming is a silly claim that has been doing the rounds along with pseudoscientific achievements of ancient Indians such as flying machines and cloning.

This facile lumping together of serious linguistic research with fringe fabrications is not only intellectually dishonest, but also deliberately malicious. It betrays a willful refusal to distinguish between the rigorous scholarly tradition of Saṃskṛta grammar — which predates many Western linguistic systems by centuries — and other, more outlandish claims.

It is also extraordinarily disingenuous of Kanisetti, — who seems to have no ethical boundaries when it comes to the disparagement of Saṃskṛta to rubbish the linguistic potential of Saṃskṛta in computation by mockingly placing NASA scientists in quotes in his own article. It is an underhanded move that casts doubt on legitimate research: the study in question, titled ‘Knowledge Representation in Sanskrit and Artificial Intelligence’, was authored by Rick Briggs, from NASA’s Ames Research Center in California and published in AI Magazine, a reputable, peer-reviewed journal in the field of artificial intelligence. The study posits that Saṃskṛta, particularly in its classical grammatical tradition, offers a naturally evolved linguistic framework that mirrors the structure and logic of modern AI semantic representation systems. Its case-based syntactic system and verb-centered sentence analysis allow for unambiguous mapping of meaning, akin to semantic nets and triples used in AI. This precision enables robust inference, abstraction, and decomposition of actions, which is essential for machine understanding of language. Briggs concludes that Saṃskṛta anticipates many of the principles now central to computational linguistics and knowledge representation, suggesting its untapped potential in advancing AI. Kanisetti dismisses Saṃskṛta’s alignment with and suitability to formal logic and syntactic precision, demonstrated in comparative studies with modern AI systems, as just another nationalist fantasy. This arrogant dismissal by Kanisetti only reveals more about his own ideological biases and does not reflect on Saṃskṛta’s potential as a language.

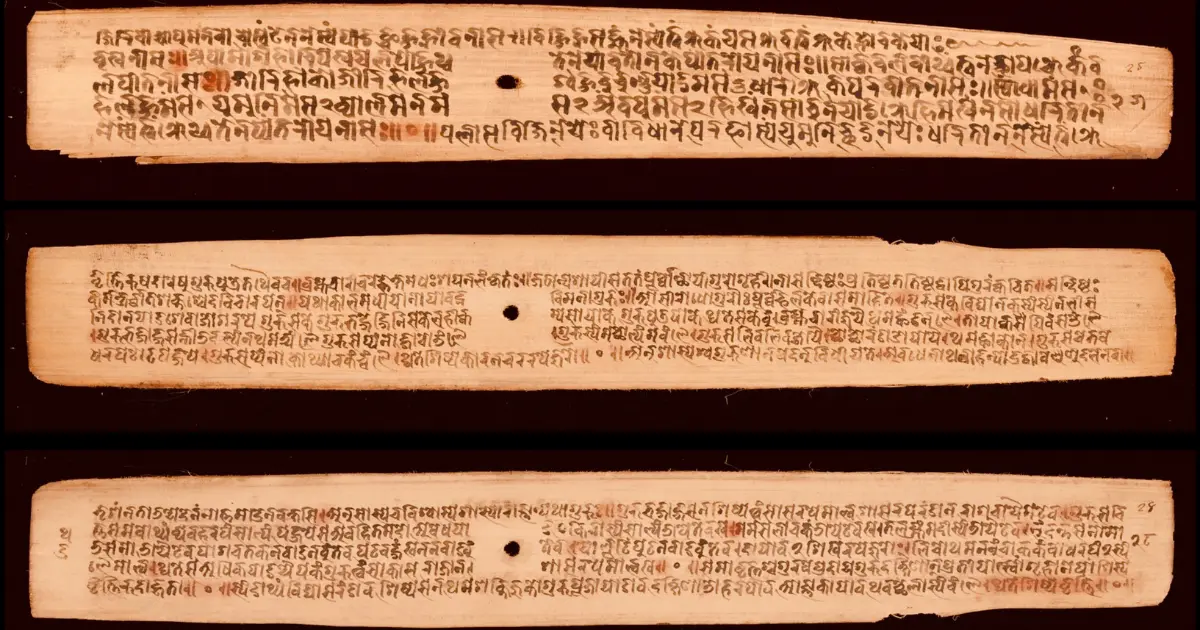

In tracing the history of Indian mathematics, Kanisetti downplays contributions such as the invention of the decimal number system, the formalization of zero as a numerical entity, early advancements in algebra, geometry, and trigonometry, and the sophisticated combinatorics of Piṅgala and Pāṇini which laid the groundwork for numerous global developments in mathematics. He concludes that Saṃskṛta arrested development, innovation, and scientific inquiry. The grammatical tradition of Saṃskṛta — especially the works of Pāṇini, Bhartṛhari, and later scholars — cannot be trivialized as Kanisetti has done, as it is these principles that laid the foundation for disciplines as diverse as logic, mathematics, philosophy, law, astronomy, and poetics. In stating that innovation in India was mostly practical and not dependent on Saṃskṛta, he conveniently ignores the reality that most of the advanced scientific, philosophical, and mathematical discourse in India, for over a millennium, was conducted in Saṃskṛta.

The language of inquiry is inseparable from the conceptual framework it enables.

Kanisetti frames the Purāṇas and Siddhāntas as dialectic entities-

Puranic authors insisted that the Earth was a flat disc surrounded by oceans, supported by elephants, turtles and serpents; the planets, stars, Sun and Moon were held to revolve in wheels above. But another set of authors, composing treatises called Siddhantas, absorbed Mediterranean conceptions such as a spherical Earth and elliptical orbits.

This is a comical assertion, especially to anyone familiar with the content and purpose of the Purāṇas and śāstras, which are both meant to serve the same purpose: to interpret Vedic wisdom, except that the Purāṇas have the additional objective of propagation of Vedic truths through storytelling. Besides, Kanisetti’s cherry-picking is lazy, as several contradictory verses can easily be cited to counter his reductive characterization of a vast and non-uniform corpus of Purāṇas. For example, the Bhāgavata Purāṇa refers to the earth as a globe in several places: bhū-golaṃ, bhū-golakaṃ (5.16.4, 5.25.12), though Kanisetti asserts otherwise.

Overall, Kanisetti’s characterization of Saṃskṛta intellectual traditions as inherently conservative and detached from observation or evidence is reductive, misleading, and frankly, outlandish. The claim that Saṃskṛta scholars prioritized theory over empirical observation ignores a vast body of evidence from texts such as the Āryabhaṭīya, Sūrya Siddhānta, and Brahmasphuṭasiddhānta, which include sophisticated methods for calculating planetary motions, eclipses, and celestial coordinates. The formulae and methods found in these texts are grounded not merely in metaphysical speculation, but in centuries of cumulative observational astronomy. Aryabhata’s proposal that eclipses are caused by the shadows of the Earth and Moon, not by Rāhu and Ketu, directly contradicts Kanisetti’s claim that 12th-century astronomers still accepted Puranic cosmology at face value. Bhāskara II, in fact, explicitly corrected such notions, while also advancing methods in calculus, spherical trigonometry, and astronomical instrumentation. Further, Kanisetti uses the occasional computational error or lack of preserved instruments to undermine the legitimacy of the entire Saṃskṛta astronomical tradition. This is not only selective butand ahistorical, especially when even European astronomy prior to Tycho Brahe and Kepler was riddled with far greater inaccuracies.

Kanisetti’s critique, then, reflects an ideological bias against India’s civilizational legacy than a balanced reading of the historical record.

As for his reading of the Arab world, it is well established by scholars including George Saliba and David Pingree himself that much of the early scientific flourishing in the region was built upon translations of Indian works. Moreover, if Arabic sources appear more advanced in instrumentation like astrolabes, it is also due in part to the geo-political stability and state patronage under the Abbasid Caliphate. Such conditions were lacking in parts of India due to waves of Muslim invasions and the consequent turmoil that they caused. The absence of more advanced instruments in India thus cannot be attributed solely to intellectual stagnation, as Kanisetti implies.

Kanisetti’s assertions grow more and more dubious as the article progresses. His claim that “the idea of scientific innovation for its own sake, to profitably harness natural principles, did not exist as it does today” is a sweeping one, made without any historical grounding or cultural nuance. Nowhere does he engage with the foundational epistemology of Hindu knowledge systems, which did not view nature as an object to be exploited, but as sacred and interconnected. Kanisetti’s idea of “harnessing” or “profiting” from nature is rooted in a Western, mechanistic worldview — especially post-Enlightenment — where nature is externalized as a raw material for extraction, contrary to the Hindu metaphysical worldview.

Kanisetti’s next claim is that Saṃskṛta was inaccessible and thus “limiting” to innovation. This characterization reflects a gross misunderstanding of the nature of intellectual transmission in ancient India. The Saṃskṛta śāstric traditions were (and are) not elitist relics, simply because they demand untold discipline and dedication to acquire expertise. The fact that rigorous training was required, not only to master the language, but also to acquire a command over the existing texts in the field in order to contribute meaningfully is not a flaw, but a testament to the traditions’ depth and conscientiousness. Frankly, this is no different from how the modern education system mandates years of formal training and study.

Kanisetti goes on to write-

Bigger changes, though, came only gradually: the Sanskrit tradition, unfortunately, had become more interested in preserving its prestige and age-old conventions, and only rarely engaged with new, ‘alien’ (and hence less prestigious) ideas.

Kanisetti’s narrative here is a textbook example of agenda-driven, colonial historiography masquerading as balanced commentary. The output of the Kerala School of Mathematics is perniciously overlooked by Kanisetti, which, between the 14th and 16th centuries, developed infinite series expansions for sine, cosine, and arc tangent functions — centuries before Newton or Leibniz — effectively laying the early foundations of calculus. It cannot be understated that the vigor of the Saṃskṛta mathematical tradition was extinguished not due to intellectual stagnation, Hindu ‘religious dogma’, or nostalgic preservation of tradition, but rather, systematically dismantled by waves of invasions followed by colonial policies that decoupled Indians from their civilizational memory. The decline was not an organic implosion due to native traditions, but a consequence of deliberate erasure and devaluation of native knowledge systems. It was a tragic interruption of one of the world's most profound intellectual traditions.

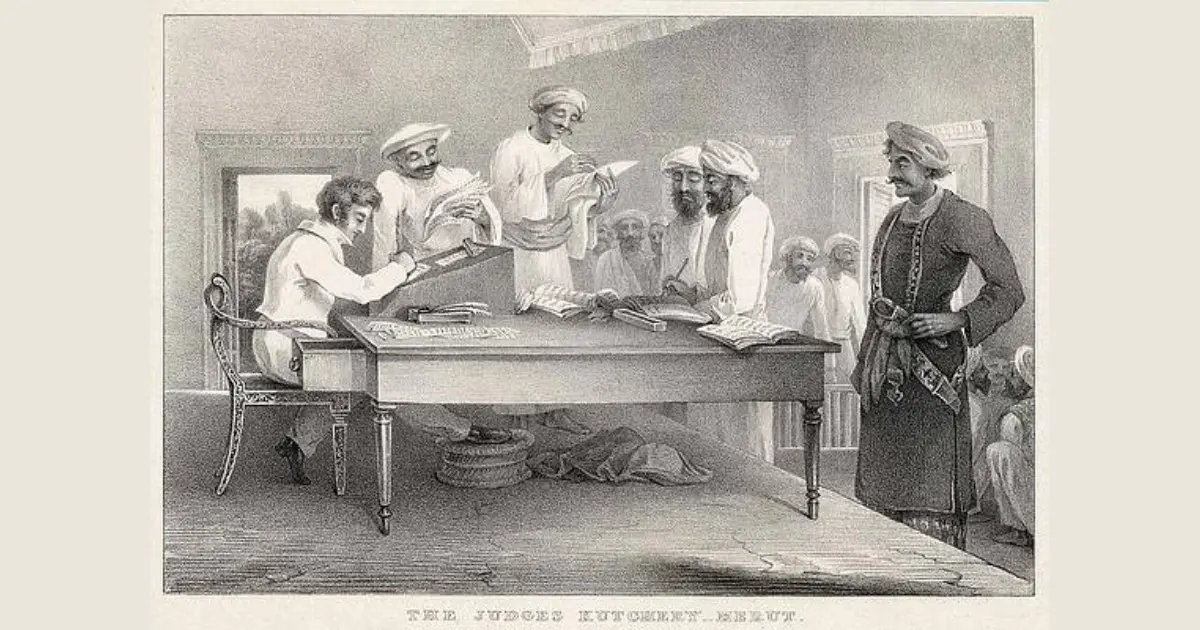

Next, Kanisetti downplays the revolutionary achievements of Indian knowledge systems by burying them under the generalization that Saṃskṛta scholars had become obsessed with prestige and resistance to innovation. This caricature ignores the vibrant commentarial traditions, empirical studies, and rigorous logic embedded in Saṃskṛta scientific thought. Worse, the depiction of British administrators like Lancelot Wilkinson as catalysts for ‘Indian scientific awakening’ rehashes the idea of a colonial “civilizing mission,” suggesting that rationality and observation were alien to the Saṃskṛta tradition. Kanisetti’s framing blatantly ignores the very nature of Nyāya, Vaiśeṣika, Jyotiṣa śāstras. Rather than acknowledging the robust, self-critical, and internally evolving nature of Indian sciences, Kanisetti projects stagnation and dependency. By reframing assimilation under colonial pressure as salvation, he reduces a rich civilizational legacy to a simplistic narrative of native decline which was then rescued by outsiders. Despite Kanisetti’s petulant whingeing, Saṃskṛta is the root of all Indian languages, and, regardless of its (supposed) stagnation or capacity for innovation, there is nothing inherently wrong with the incorporation of the mother language into school curricula.

Kanisetti finally brings his warped and wholly inaccurate rant against Saṃskṛta to an end through his closing paragraph, where, he cloaks his shallow, nonsensical universalism in the garb of humility. However, the irony is glaring: he warns against linguistic chauvinism while simultaneously dismissing Saṃskṛta outright, despite its demonstrable merits. Kanisetti engages in a crude conflation by stating that because Saṃskṛta is revered in religious tradition as divine, any effort to highlight its scientific value is necessarily driven by religious fanaticism. To then invoke “mathematics, reason, and evidence” as some neutral, disembodied global ideal, while erasing one of the key civilizations that shaped these fields long before Europe enlightenment, reeks of intellectual dishonesty. Saṃskṛta was not merely a medium of religion and ritual: it was the vehicle for some of the most advanced mathematical, astronomical, and philosophical insights in human history. If Kanisetti truly valued the “heritage of all humanity,” then he should begin by acknowledging the depth, rigor, and influence of Saṃskṛta as part of that heritage. Instead, he dismisses it with patronizing platitudes that veil cultural amnesia as progressive thinking. Kanisetti’s piece ultimately reads less like a critique grounded in linguistic or historical understanding and more like a reactionary harangue against anything that might reflect positively on India’s intellectual past.

Note: We reached out to The Print regarding the publication of (a prior version of) this rebuttal. They declined, making clear their unwillingness to platform alternative viewpoints or encourage genuine intellectual debate.