As debates on the direction that public policy must take rage on, Bṛhat’s flagship course on Civilizational Public Policy, Nītividhāna, is geared up for another iteration. It is a genuine effort towards cultivating a dharma-centric, culture-compatible public policy for an emergent new Bhārata.

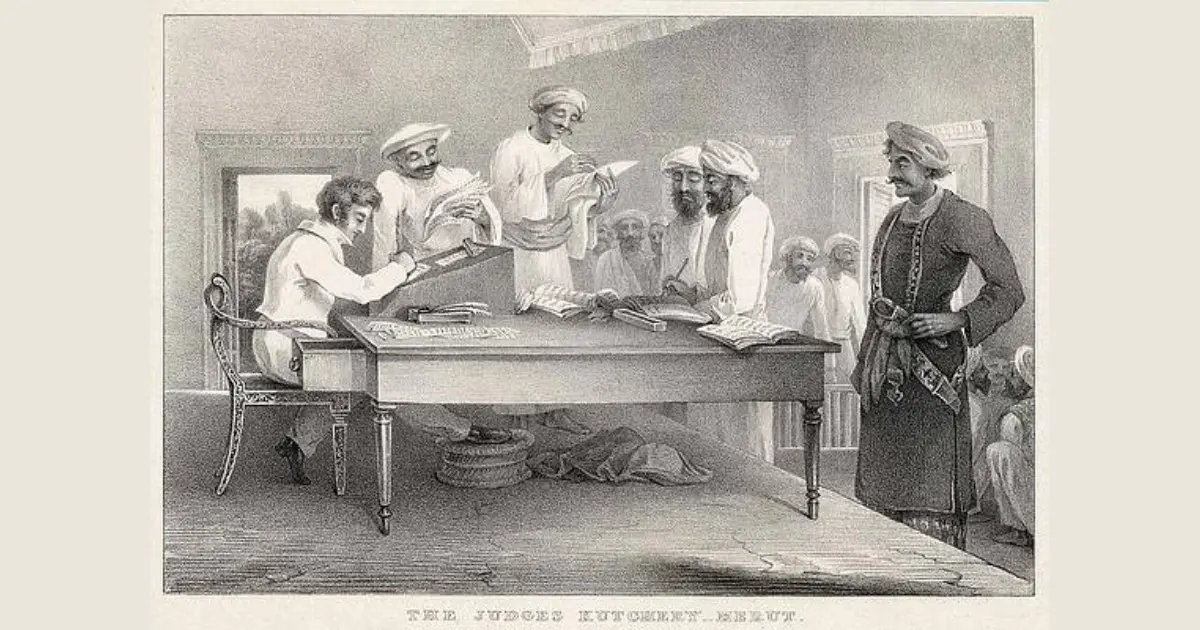

For centuries prior to European arrival, Bhārata developed and sustained sophisticated and grounded political systems based on dharma and ṛta. The British-European political system asserted political jurisdiction through force dispossession. The ensuing forms of public administration and governance have been derived almost entirely from foreign British-European liberal ideas and prescriptions. The major institutions, the theory of state (including the grundnorm or legal basis of the power of the state) and governance mechanisms have been derived from Western ideas and philosophies. In contrast, the notion of a civilization-state attempts to mobilize civilization-state ideology to counter liberal Western values and Western dominance, working within the confines of the political and democratic system already in place. ‘Civilization’ — based on religious and cultural belief systems — is viewed as a unifying force, providing a foundational identity for a people and superseding considerations such as region, language, race, and other characteristics.

Reclaiming Indigeneity: Recognizing the Need for ‘Civilizational’ Public Policy

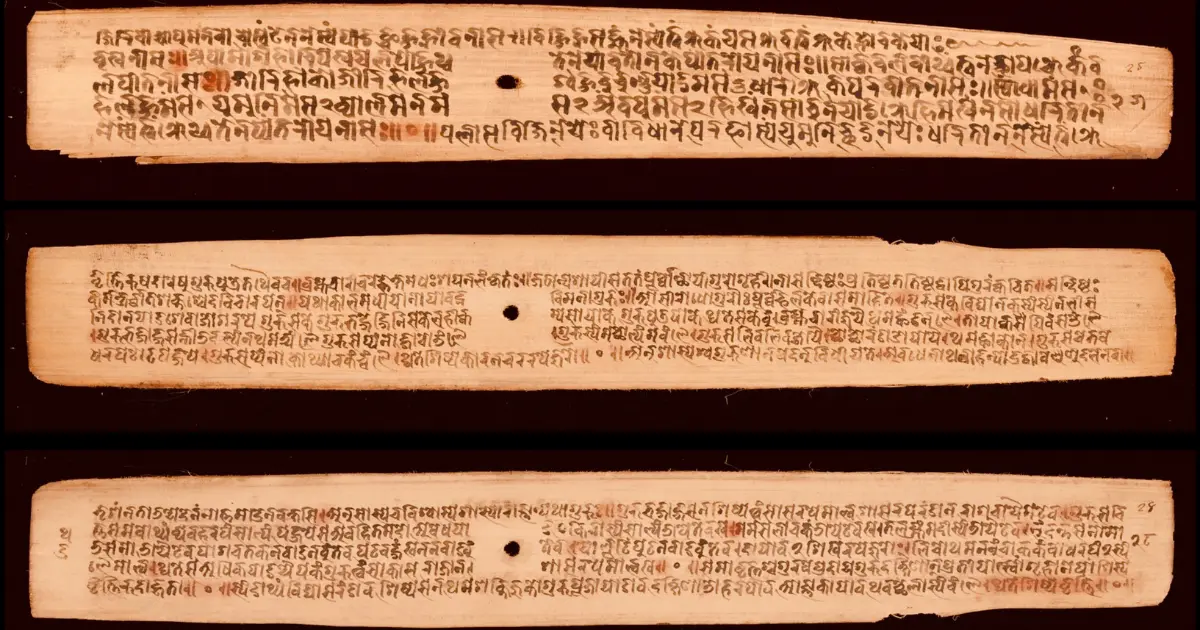

Ancient civilizations have always had their own distinct institutions, governance systems and governance philosophies that provided structure to the life of people, society and the nation, and these structures can be revived to form the basis for indigenous-inspired governance now and in the future. Colonization disrupted indigenous political and governance systems, and undermined the sovereignty of civilizations and the legitimacy of their institutions. Since then, colonized nations have been grappling with the issue of how to best govern their own people, preserve land, sovereignty and culture; and respond to the demands of their citizens, all the while creating a surplus of wealth. The importance of cultural compatibility in policy making and institutional development is key to the adoption of good governance practices. Indigenous institutional design and functioning, especially in the realms of education, environment and economic development looks beyond the narrow and failed pathways initiated by Western models.

In contemporary Bhārata, policy making is fraught with the issues of not only a dreadful lack of literature and research informing public policy, but also the lack of a long-term, unifying vision. Policy must not move with the whims of the political tides — rather, regardless of superficial rhetoric, policy must be firmly rooted and adhere to a unified direction based on decolonization, national unity and economic development. The need of the hour is to indigenize policy in order to diverge from the dominant British-European political framework that continues to assert jurisdiction through force.

Modernization as an Agenda in Public Policy

Modernization is a mega force for the trajectory of public policy in the country that has curtailed the incorporation of knowledge from traditional and historical sources into what is seen as a ‘rational’ and ‘progressive’ growth. Western theories of development were evolved in the Cold War era as Western ideologies of dominance, with the intent to strengthen the foothold of colonial rule across the globe by European powers. Modernization and current development models are exclusionary, yet have the backing of Western governments through international lobbying forces, and have been universalized. These factors determine the prominence of public policies that undermine the chances of Indian Knowledge Systems (IKS)-based crafting of policy and law. It is important to highlight the distinctive identity of Bhārata as a civilization-state in contrast with a more narrowly grounded twentieth century entity of a ‘nation-state’ that imposes predetermined notions of progress and development by default. The government and its arms, even in the 21st century, exhibit the need to ‘civilize’ the people in order that they leave behind their ‘backwardness’ and aggressively adopt modernity in all its forms.

Nation-building and Institutionalism

Institutionalism defines institutions as enduring and resilient collections of rules and practices that prescribe appropriate behavior between actors to engage in political and economic activity. Institutions in the modern day are valued for their ability to stabilize the political order and power relationships within society. Institutions ‘set the rules’, especially but not limited to formal rules such as constitutions and laws and informal rules and norms that are codes of conduct. Institutionalization as per the Western system of government, therefore, has been a crucial tool for colonization to reinforce Eurocentrism.

From a nation-building perspective, the development of enduring institutions is a necessary step in the political and economic development of society. At its root, nation-building emerges from a policy trajectory of social evolution in which a universalizing, totalizing attitude of Western nations sought to set ‘backward’ countries on a path towards democracy, capitalism and the international rule of law. Therefore, though nation-building cannot be the sole policy consideration to orient towards, it is a helpful analytical framework to understand patterns of development. Conceptions of nations and nationalism may be cast into two rival frameworks: constructivism and primordialism. Constructivist views of a nation situate state development and group attachments as socially constructed, invented or imagined, while primordialists view nations as perennial, historically constituted entities in which group attachments are shaped by birth and kinship. From the primordial perspective, modern nations emerge from pre-existing affiliations and become more durable with time. The collective idea of a nation, therefore, is critical in developing countries such as Bhārata in order to accurately ascertain policy interventions and to build constructive national identities and nationalism. In contrast, theories of new institutionalism require a form of bureaucratic development, which emphasizes the creation of a meritocratic bureaucracy—a system in which social organization is based on the rule of law, and property and individual rights — rather than kinship and community bonds.

Formalizing Indigenous Institutions

The indigenous or traditional notion of an institution is radically different and more expansive than its Western counterpart. Traditional institutions are not centered merely around creating a favorable environment for transactions or setting the rules for politicking and interaction, but rather, have a deeper meaning, and set wide rules and norms for behavior and societal relationships. Indigenous institutions acknowledge phenomena beyond the natural world — they engage on personal, social, political, and even spiritual plane, relying on wisdom and knowledge systems that existed prior to the creation of Western idea of democracy. Indigenous institutions seek to achieve balance and harmony and reinforce values, lifestyles and ways of being. For policy considerations, legitimizing and recognising indigenous institutions and knowledge to be on par with Western is crucial to the creation of policy and development tailored to the populace and national interest.

This is where Nītividhāna, the public-policy program offered by Bṛhat aims to root policy in the bedrock of the civilization — a Dharma-based society and political philosophy.