Adieu le passé, c’est aussi adieu la postérité. (Farewell to the past is also farewell to posterity) Jules Michelet1

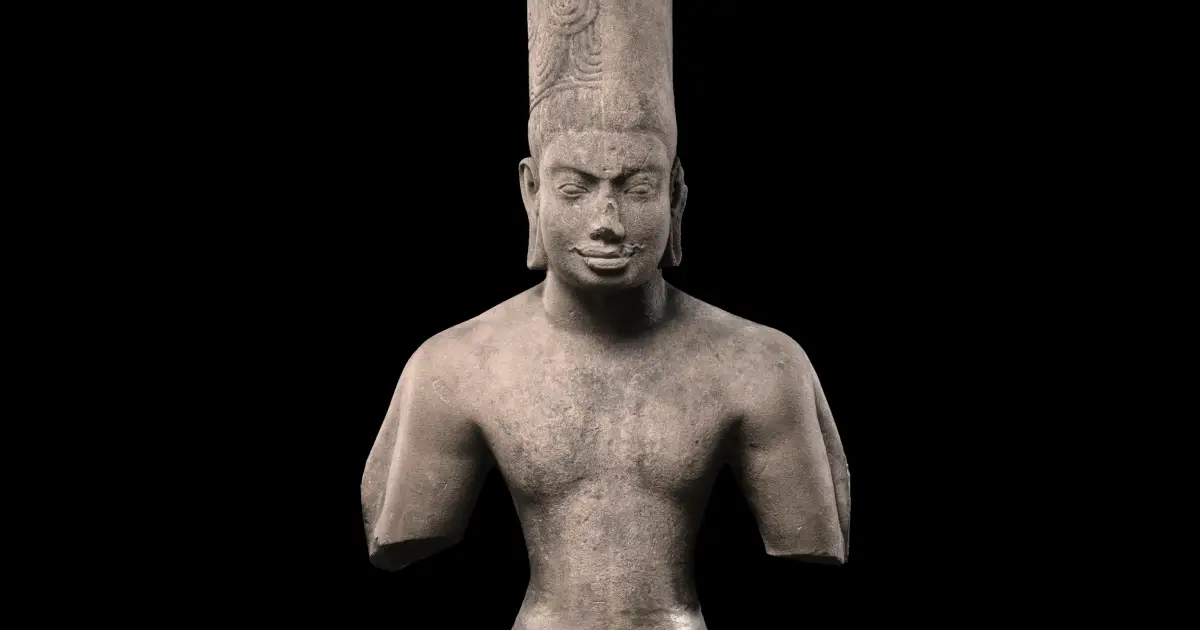

In 2023, a Cambodian dancer and educator Sophiline Cheam-Shapiro was kicked out of The Metropolitan Museum of Art (The Met) in New York for performing a traditional Cambodian dance before a Khmer sculpture of Harihara2. Sophiline is a practitioner of a nearly extinct classical dance which originated as a form of ritual prayer in ancient Cambodia. She states that “Whenever I visit museums around the world that house Khmer antiquities, I pray to the gods and ancestors that inhabit them. Sometimes I simply put my hands together and chant. Other times I move. This is my tradition. It is an essential part of my identity and my relationship to these objects.” Sophiline is a passionate advocate of the returning stolen Khmer antiquities, knowing that even if they ended up in museums in Cambodia, no Cambodian would ever stop her from worshiping her Gods. Cambodia has been demanding the return of Khmer artifacts held by The Met, eager to restore them to the temples they had been looted from, to be worshiped by locals in the manner they had been for centuries.

Calls for restitution of culturally significant artifacts taken by European nations from former colonies grow louder, and they can no longer be brushed under the carpet through institutional silence and State inaction. Traditional arguments for retaining objects acquired through colonial violence or oppression are quickly losing credibility. This paradigm shift stems from a multitude of factors: internal changes within museums, persistent resistance to colonial injustice, the enduring impact of colonial plunder on states and diaspora communities, increased public awareness, generational shifts, and the influence of “multidirectional memory," which fosters new debates on decolonization3.

In addition, the rise of social media and repositories of digital images has made it harder to obscure contested artifacts in collections, conceal violent histories, or rely on pretexts and delays. The increased transparency has also made the continuing colonial violence more apparent. Restitution and repatriation4 are crucial, as reconnecting with these objects is vital for preserving the identities and histories of the Global South while also reshaping knowledge systems and confronting colonial legacies. This article explores the history and the evolution of the idea of restitution, impediments to restitution, and discusses potential solutions to facilitate the process.

“Common Heritage of Mankind”

This idea of cultural heritage as an 'international public good' and the ‘common heritage of mankind’ in International Law, has been the basis for justifying the “protection” of culture, albeit monopolized by the West. It initially emerged from the Preamble of the Hague Convention for the Protection of Cultural Property in the Event of Armed Conflict, 1954, in which it was stated that “damage to cultural property belonging to any people whatsoever means damage to the cultural heritage of all mankind," setting the stage for eventually shaping the future policies related to cultural property. Post-war, the attention shifted to the burgeoning international art market, mainly the illegal trafficking and commercialization, the trade driven by rich collectors and museums abroad.

UNESCO’s Cultural Heritage Conventions, especially the 1970 Convention on the Means of Prohibiting and Preventing the Illicit Import, Export and Transfer of Ownership of Cultural Property5 and international criminal law consolidated public concern and attempted to formulate international legal controls aimed at preventing trafficking and illicit trade but have not been effective at preventing colonial exploitation and loot.

A resolution adopted by the UN General Assembly in 1973 on the ‘Restitution of Works of Arts to Countries Victims of Expropriation’ addressed the “removal” without payment of works of art through the exploitation of imperial power stemming from colonial or foreign occupation and called for the ‘prompt restitution to a country of its objects of art, monuments, museum pieces, manuscripts and documents by another country, without charge6. However, despite mountains of evidence of “removals” — especially from colonized nations — such resolutions have had little effect on initiating repatriation in good faith.

Anthropologist, art historian and museum curator Dan Hicks in his Brutish Museums says that museums are spaces of knowledge, curated to enchant, and reconstruct the world from the perspective of the colonizer7. He recounts the audacious manner in which American and European museum directors issued a “Declaration on the Importance and Value of Universal Museums” wherein demands for restitution and return were framed as narrow, nationalistic self-interest of the indigenous peoples of the Global South, projecting Anglo-American museums as arbiters of the heritage of the whole of humankind8 — though situated in the Global North and catering to audiences there.

The Case for Restitution

And what of the museums, of which Europe is so proud? It would have been better, all things considered, if it had never been necessary to open them. Better if the Europeans had allowed the civilisations beyond the Continent of Europe to live alongside them, dynamic and prosperous, whole and unmutilated. Better if they had let those civilisations develop and flourish rather than offering up scattered limbs, these dead limbs, duly labeled, for us to admire. Aimé Césaire, Discours sur le colonialisme, 1955 (translated by Dan Hicks)

Cultural property is inextricably tied to identity and self-image, and for indigenous peoples, history and culture are central to decolonization, self-actualization and self-determination. Cultural losses suffered by indigenous peoples were fuelled by the “free trade agenda of Anglo-American States, and their promotion of an unfettered art market”9 that benefitted both State institutions and private parties. More often than not, the cultures and communities that experienced the loss are still alive and flourishing, and probably still make use of the objects displaced for ceremonial rites and ritual purposes.

For instance, the Afo-A-Kom sculpture which was stolen from the Kom people of Cameroon, and exported to the United States was stated to be “beyond value” by the First Secretary of the Cameroon Embassy in the United States, who passionately declared that the sculpture was “the heart of the Kom, what unifies the tribe, the spirit of the nation, what holds us together. It is not an object of art for sale and could not be”.10

The nation and culture which is the fount of the cultural property in question is certainly better-equipped to be enriched by the heritage, to maximize the feeling of pride and belonging in its peoples. The economic and commercial benefits — whether through profits via museum sales, increased tourism, or auction — of another culture’s civilizational inheritance and intellectual property by Western museums cannot be ignored. It is undeniable that preserved cultural heritage consolidates cultural and historical continuity for the nation.

Vrdoljak in International Law, Museums, and the Return of Cultural Objects11 proposes a framework for the purpose of restitution being rooted in three distinct rationales:

- Cultural Objects as ‘sacred property’: territoriality and establishing the link between people, land and cultural property.

- Righting Historical International Wrongs: redressal for discriminatory, colonial or genocidal practices of the Anglo-American world.

- Enabling Self-Determination and Reconciliation of Indigenous people across the world.

In his plea for the “Return of an Irreplaceable Cultural Heritage to those who Created It”12, former Director-General of UNESCO, Amadou-Mahtar M'Bow poignantly stated that the “vicissitudes of history have nevertheless robbed many peoples of a priceless portion of this inheritance in which their enduring identity finds its embodiment” and called for the return of cultural assets to their country of origin, appealing to member States, media organizations, academia, institutions, scholars, and activists to throw their weight behind the process of restitution in order to enable people to re-discover their heritage and cultural memory and identify with their civilizational past.

Preservation in situ

The purpose of restitution is to restore the state of affairs as it was prior to the displacement of cultural heritage restitutio in integrum13. After all, the historical and epistemological value of the artifacts are maximized by its continued presence within their specific geographical and cultural context. The notion can be distinguished from the concept of ‘repatriation’, i.e., restoration of cultural property within a State, and ‘return’, when the cultural heritage in question was taken from the territory during a period of occupation or in the context of illegal export, without necessarily involving the breach of any international norms or obligations (Kowalski, 1998). Moreover, the return of cultural artifacts need not necessarily be to a State or State entity but may also benefit an ethnic or indigenous group, or religious community to which it may hold an exalted or special significance in order to replace the object in its original cultural context.

Issues

Former colonies and disadvantaged nations attempt to trace illegally or unethically acquired art and artifacts to museums worldwide and present a case for their return from states whose public or private institutions have acquired them for monetary gain. However, even in cases where there exists clear documentary evidence of illegal provenance, restitution remains a herculean task to accomplish. There are multiple issues that serve as obstacles to the creation of effective channels for return and repatriation. First, there exists a massive market for stolen art and cultural property globally, which is a clear impediment to restitution efforts. Customs and border control and the enforcement of domestic law also tend to be less stringent in poorer nations, where the looting of archeological or historical sites is driven by the readiness of purchasers abroad. Museums and private collectors, to conceal provenances, often label objects as “gifts” in order to subvert and effectively escape legal scrutiny. The drivers and stakeholders of this market are not only concentrated in rich first world nations, but also form the social, economic and political elite of these nations ̶ capable of exerting considerable influence and power in order to legitimize and conduct business and sales legally14. There may also arise the possibility of conflict between domestic and international law and jurisdiction on questions of legality and ownership. The hope is that museums and collectors alike work towards the righting of historical wrongs, and the art community must self-reflect and find methods of creating taboos around the possession of tainted cultural artifacts.

The Way Forward

The reliance placed on international law and museum policy has proven to be ineffective at addressing restitution claims, and has been a failure on the part of the global community. International law is paradoxically built on imperial notions and power relations, while simultaneously being couched in contemporary discussions and attempts to decolonize it ̶ “law is both the culprit and the potential remedy”15. The destruction of the sacred connection between land, people, and their cultural heritage is an established colonial agenda and central to its policies of discrimination, forced assimilation, and genocide.

Accordingly, throughout the colonial period, the various international and domestic laws that were formulated unilaterally benefited western archaeologists and collectors rather than deterring illegal export and enabling cultural preservation due to the lax provisions enabling the acquisition and export of antiquities. Moreover, theories of justice fail to address ongoing colonial asymmetries born of historical realities. Revisiting international laws relating to restitution that are designed to benefit, perpetuate or wholly exonerate imperial-colonial exploitation and profiteering is only one of the many actions that must be taken going forward. There is also a strong case to be made for the strengthening of international cooperation and bilateral agreements for the return, restitution, and/or forfeiture of cultural property acquired from the third world/source nations.

For a subjugated people, the alienation of cultural artifacts epitomizes a profound disenfranchisement—the forfeiture of their sovereignty over their land, resources, and most of all, their identity.

Footnotes

- Quoted in Manfred Lachs (1985) ‘The defences of culture’, Museum International, 37:3, 167-168, DOI: 10.1111/j.1468-0033.1985.tb00577.

- Cheam-Shapiro, S. (2023, March 22). Met museum kicked me out for praying to my ancestral gods. Hyperallergic.

- Stahn, Carsten, 'Acknowledging the Past, Righting the Future: Changing Ethical and Legal Frames', Confronting Colonial Objects: Histories, Legalities, and Access to Culture, Cultural Heritage Law and Policy (Oxford, 2023; online edn, Oxford Academic, 19 Oct. 2023), accessed 22 Nov. 2024. p. 414-415

- The terms restitution and repatriation are often used interchangeably, however, there is a distinction between the two. Repatriation refers to the legal, administrative and logistical matters of returning across national borders at the request of the government. Restitution is the return of cultural objects to individuals, communities or institutions.

- Convention on the Means of Prohibiting and Preventing the Illicit Import, Export and Transfer of Ownership of Cultural Property, The General Conference of the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization, meeting in Paris from 12 October to 14 November 1970

- UN Doc. A/Res/3187 (XXVIII)

- Hicks, Dan. The Brutish Museums: The Benin Bronzes, Colonial Violence and Cultural Restitution. United Kingdom, Pluto Press, 2021.

- Ibid.

- Vrdoljak, Ana Filipa. International Law, Museums and the Return of Cultural Objects. United Kingdom, Cambridge University Press, 2006

- Forrest, C. (2012). International Law and the Protection of Cultural Heritage. United Kingdom: Taylor & Francis

- Vrdoljak, Ana Filipa. International Law, Museums and the Return of Cultural Objects. United Kingdom, Cambridge University Press, 2006

- A Plea for the Return of an Irreplaceable Cultural Heritage to those who Created It, 7 June 1978, Amadou-Mahtar M’Bow, Director-General, UNESCO

- W.W. Kowalski, Art Treasures and War, Leicester: Institute of Art and Law, 1998

- Graham, Gael M. “Protection and Reversion of Cultural Property: Issues of Definition and Justification.” The International Lawyer 21, no. 3 (1987): 755‒93.

- Stahn, C. (2020). Reckoning with colonial injustice: International law as culprit and as remedy? Leiden Journal of International Law, 33(4), 823-835. doi:10.1017/S0922156520000370