This article is Part 2 in a series summarizing the concepts expounded by Śrī Chittaranjan Naik in his piece, The Realist View of Advaita. The link to the original series has been provided and provides a comprehensive explanation of Advaita doctrines.

Read Part 1 of the series here.

Ontology

Dravya (Substance) as The Ground of Being

The important points are:

- Substance, revealed in the perception of an object as the existing thing, is never experienced by itself. Immanent as the ground in the things experienced, it is the existential core of the thing and the object's substantiality. A dream horse is insubstantial, but the reality immanent in the perception of a real-world horse is the existentiality of substance.

- Substance is also a unity of all sensual and non-sensual predicates that characterise a thing. We perceive objects as possessing sensual attributes. We do not see complex colours and shapes floating; rather, we see apples, tables, and so on with these qualities. The perception of a tree is immediate and not an experience of agglomeration of sensations bundled into a unity, as some empiricists say. This is an inference that supersedes an empirical fact.

- All the attributes are coterminous with the substance. Śrī Ādi Śaṅkarācārya (Śaṅkara) refutes the duality of substance and attributes by refuting the relationship of inherence which leads to an infinite regress. Substance is the existent, and attributes are its descriptions. It is this truth embedded in language wherein identity is predicated between the substance and attribute by a subject-predicate form: 'An apple is red'.

- Substance, bare and abstracted from attributes, is indiscernible and noumenal. Every manifestation has an existential core, even the form given by the name mirage or dream horse. All these are in the noumenal ground of Existence, One and not many, because substance, qua substance, is bare and indiscernible. There cannot be a difference between indiscernible 'things', because difference is nothing but a discernible. Therefore, substance, divested of attributes, is One and indivisible.

Thus, there is nothing that is non-existent, but only Existence manifesting non-existence as a manifestation of its attributions. Experientially, things may or may not exist, but at a deeper level, they are all unreal, belonging to the chimaera of substantiality bestowed by names and forms. And yet, at the deepest level, they are ultimately all real, with their existential core being the noumenal ground of Existence. There is nothing but Existence, even in the unreal, it being only a mode of the Real.

Vivartavāda and Ontology

The world is unreal because it exists in the middle but not in the beginning and the end. When things exist in the middle, it means -

a) either that they are non-existent (because of their absence both yesterday and tomorrow), or

b) it was always there and that its coming into existence is merely a false seeming. Advaita, adhering to its tenet of satkāryavāda, affirms the second and rejects the first position.

The fundamental ground of logic in understanding creation, destruction, and change is that a thing is identical to itself. There is an unchanging principle or ‘being' of the object which stays the same despite changing attributes. This 'being of the object' is substance, as we have seen. As an example, a hypothetical circular coin made of wax can be changed to a square form. Different attributes, each of which is unchanging (the square is not a circle), were displayed in the 'change' attributed to the object.

The law of identity is not violated, and yet change is possible as the showing forth of attributes that are pre-existent in the substantial ground. Change is the manifesting dynamism of things that are each unchanging. This dynamism is real and is called 'Time' (Kāla). In truth, there is nothing born, nothing destroyed; everything is eternal in the infinite nature of Brahman.

Śaṅkara argues that the effect already exists prior to its production. Manifestation means a pre-existence that comes within a range of perception, like a jar hidden by darkness, which becomes perceptible with the falling of light. Even when the sun rises, we cannot perceive a non-existent jar. Every effect has two kinds of obstructions. A jar after manifestation from its components has darkness and walls as obstructions to perception. However, before manifestation from the clay, the obstruction consists of particles of clay remaining as some other effect, such as a lump.

‘Destroyed', 'produced', 'existence' and 'non-existence' depend on this two-fold character of manifestation and disappearance. Śaṅkara finally concludes that separable or inseparable connection is possible between two positive entities only, not between an entity and a nonentity, nor between two nonentities.

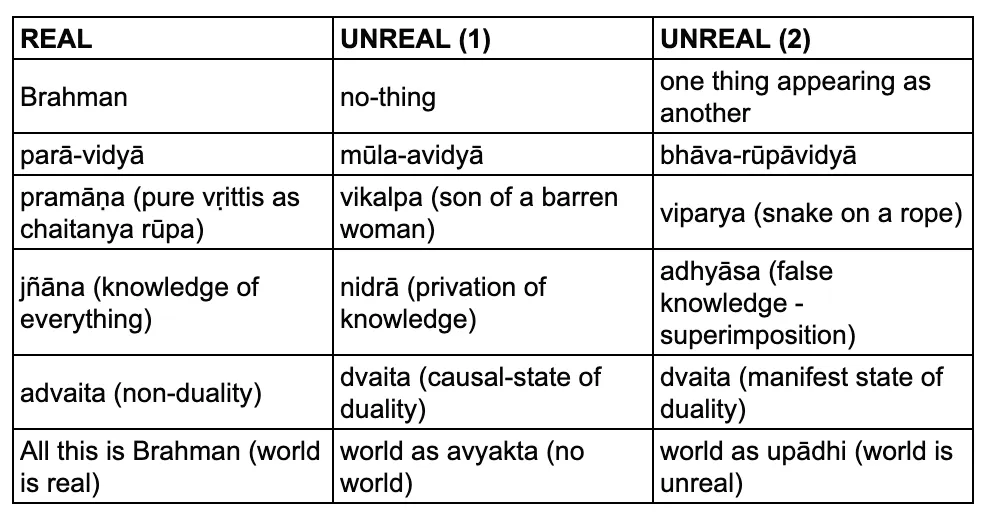

The Real and Unreal in Advaita

The absolutely unreal is the son of a barren woman — a meaningless term. The real, all that is seen and conceived, is the opposite of the unreal and hence, all that has meaning. The second meaning of unreal is adhyāsa, the mistaking of one thing for another. Our way of cognition through both the senses and mind is responsible for this superimposition.

Substance is the 'thing' perceived, and the attributes are perceived as being 'of the thing' perceived. The senses grasp the attributes, but the mind grasps the thing where the attributes inhere. Adhyasa takes place when the attributes are seen, but the substance or the ‘thing’ is falsely believed to be something else by the mind.

Vyāvaharika is the state when the sentient Substance (Brahman) of the world is concealed and the mind rushes out to grasp the insentient prakṛti (nature) as the substance. This 'world' superimposed on Brahman is false. Adhyāsa is a natural feature of the people in this world. The world in the continuum of Brahman is, however, the reality of Advaita, in which there can be no superimposition.

Advaita

Difference

If the universe of names and forms is real, then why is Brahman described as formless and nameless? The issue of distinction represents the ultimate frontier of philosophy, defining the boundaries of logic and language. Brahman, like the yarn in the cloth, is the material cause of the universe. Then how indeed does the cloth become false when the yarn is true? A mere assertion that whatever pertains to names and forms is false would amount to a dogma, and this negation would make Advaita nihilistic.

Whether the difference is in material cause or attribute distinctiveness, it is not logical. Therefore, difference is an admixture of truth and falsity. It is not possible to speak of the true nature of that which partakes of falsity — 'anirvacanīya'. The confusion between 'sameness' and 'difference' is the primordial confusion since a beginningless past. We must now approach difference from another direction.

Words and Denotation

Advaita says that a word does not point to the particular but only to the universal. Even when an object 'changes', its name remains the same. The Nayyāyikas (Logicians), the Vayyākaraṇas (Grammarians), and those from other schools of Vedānta hold that words point to both the universal and the particular. Advaita refutes this by saying that if this were the case, then it would occasion a new name every time a different attribute is seen, as the combination of universal and particular (U+P) would be a new combination. An infinite number of names for the object makes it unreasonable.

Gautama (the founder of Nyāya) objects and says that this is not right because the manifestation of a universal depends on individuality and configuration. The Advaita response is that there is no difference between the sāmānya (universal) and viśeṣa (particular). If disparate and non-conjunct, then a viśeṣa could never belong to a species. Again, according to the Śruti, the truth is revealed when we withdraw from the world of sense objects. Śruti would not be misleading here in its objective. Then, how is it that by knowing the Self, everything comes to be known?

Sāmānya (Universal) and Viśeṣa (Particular)

Words denote only universals; the latter are objects themselves; otherwise, words cannot point to objects. Universals necessarily exist, and without them, there cannot be recognition. For cognition of 'this' (a cow, for example), it requires a recognition of a universal ‘thisness’ (cowness). A universal is unthinkable because the very act of thinking particularises it. Failure to see universals as unthinkable and that thinking is always particularised has caused much befuddlement in modern philosophy.

A universal, formless, and non- spatio-temporal entity is yet the essence of form. There are no unspecified particulars into which universals enter or 'participate'. The term 'participate' is metaphorical. There can be nothing except amorphousness without universals. A universal makes a thing what it is. It is not possible for the particular to be more than the universal. Thus, so far as the universal to become a particular is concerned, there is no difference between the universal and the particular. But the other way around — a particular is not the universal itself. It is possible for a particular cow to be absent from another instance where the universal is present, i.e., in another cow. Thus, universals are present wherever there is a particular, but the reverse is not true. However, a particular is wholly nothing but a universal, albeit a partial vision.

The universal is the complete infinitude of attributes of the thing, of say 'cow', and it pervades all particulars. A universal can manifest simultaneously in all instances of its particulars because it has no form and is not spatio-temporal. Words denote universals. Therefore, the world of forms that is denoted by names is the “sameness” of universals. The latter is the formless whole of all its particulars — the very knowledge of things in the omniscience of Brahman. The formless Brahman therefore contains the infinitude of all that was, is, and will be. It is the intelligence that carries infinite universals in Its ineffable formlessness and undisturbed sameness.

Avacchedavāda

The world of sense is the world of 'concrete' particulars, of the limitedness of the unlimited. This is avacchedavāda, the doctrine of the falseness of the seeming limitedness of the unlimited. Therefore, the negation that the entire world is false is a negation of the limited as the true form of the unlimited. This is ābhāsavāda, and yet, in a perfectly logical manner, there is nothing excluded from Reality in the negation. Reality is full (pūrṇam).

In the Bhāṣya to the Māṇḍūkya Upaniṣad, Śaṅkara elucidates the four quarters, or pādas, that Brahman possesses.The first three – Viśva, Taijasa and Prājña – are successively merged into the fourth, or Turīya. Thus, the elimination of both name and form, that is different than Brahman, is the limitedness of the names and forms of the world of sense; and what is attained is the unlimited world, in which all the previous three gain identity. The smaller units lose their individuality in the bigger ones. Hence, Viśva merges in Taijasa, Taijasa in Prājña, and Prājña in Turīya.

Brahman, being different from both name and form, is its transcendence from them. The word 'transcend' does not mean a spatial or temporal separation but a distinction of the subsuming principle. A metaphor might be Einsteinian physics subsuming Newtonian physics without rejecting it. There is nothing negated here — a blade of grass, a speck of light, a mite in the moonbeam, a thought. The nirguna Brahman is also gunapoorna.

The Mystical Reality

Reality is mystical, where the magic of words plays upon non-duality and binds us to plurality. A word is essentially one with Brahman as parā vāk. It gives rise to the paśyantī — the causal seed. In its middling state, madhyamā presents the forms in ideality. Finally, the created world manifests as vaikharī. The mystery is that the word points to the same object in all its stages. Difference arises through Vāk. It is the heart of the mystical (Māyā), the inexplicable power of the Lord to make many out of One while still remaining immutably One. The eye of a mystic in Sahaja samādhi sees the One in All and the All in One.

Īśvara

The Origin

Who is there who truly knows, and who can say, Whence this unfathomed world, and from what cause? Nay, even the gods were not! Who, then, can know? The source from which this universe hath sprung, that source and that alone, which bears it up – none else: THAT, THAT alone, Lord of the worlds, in its own self-contained, immaculate,As are the heavens above, THAT alone knows The truth of what Itself hath made – none else! The Ṛg-Veda Hymn of Creation

The Śruti attributes the origin of the universe to Īśvara. Śaṅkara explains in Brahma Sūtra Bhāṣya:

Brahman is the yoni… It goes without saying that that great Being has absolute omniscience and omnipotence, since from Him emerge the Ṛg-Veda, etc. – divided into many branches and constituting the source of classification into gods, animals, men, castes, stages of life, etc., and the source of all kinds of knowledge… Those that are called the Rg-Veda, are but the exhalation of this great Being.

On The Meaningful Use Of Words

Entropy postulates a tendency to chaos and disorder in the universe. The probability of parts of a clock spontaneously arranging themselves is near zero. Yet, entropy is continuously violated, astonishingly unnoticed, in the form of endless ordered structures (beehives, gathering of honey, anthills, seeds growing into trees, car productions, microchip productions, aeroplanes flying). The loci of these tendencies to order are living beings. Life, or intelligence, brings order to the chaotic inanimate matter.

Discussions on efficient causality have often been obscured by improper language use. Omniscience is understood as a manifestation of avidyā. This is unreasonable. Beauty is not a manifestation of ugliness. Words must be employed in consideration of their meanings, or there would be universal confusion. By definition, avidyā is lack of knowledge. Driving and cooking, when undertaken with knowledge, lead to the intended goals. Intelligent, goal-orientated actions are disruptive of the closed systems within which the principle of entropy operates.

A rare spontaneous assembling of one clock from its parts might happen, but a repeated assembly would need an extraneous factor, the directedness of intelligence. Only vidyā with these connotations — intelligence, design, and goal-orientation — can bring about order and regularity. Avidyā, with neither intelligence nor directedness, may contribute only to chaos. Therefore, it is intelligence rather than avidyā that is the efficient cause of the universe. We should understand Māyā as the power that Brahman uses to create this universe. Māyā is not avidyā.

Īśvara, Māyā, and Avidyā

The confusion between avidyā and Māyā arises from a misinterpretation of the Bhāṣya, wherein it is stated that the omniscience (all-knowing) and omnipotence (unlimited power) of God are contingent upon the nescience of the jīva. The word 'contingent' here implies a condition upon which something else happens. Avidyā is the condition, and what happens is the response of Reality to that condition. The response springs from its innate power, given the contingency of avidyā and the accumulation of karma caused by it.

Avidyā is not the cause but is the contingent factor, like the wall of obstacles breaking to let waters flow, upon which the very nature of Brahman 'acts'. Because Brahman acts by nature, He lacks agency in His actions, as they stem from His own immovable nature. Māyā is Īśvara's incomprehensible power of creation in response to avidyā. The bringing forth is done by a power of projection, or vikṣepa śakti. Particularisation hides the infinitude of the universal. This is āvaraṇa (hiding) śakti.

The knowing eye (the third eye) knows the infinity even in the particular. Avidyā takes the finite for the infinite. Īśvara has no avidyā. Vikṣepa and Āvaraṇa are the capacities of his infinite power — the power of Māyā. Existence and the magical power of Existence are not two. They are Īśvara and His Māyā; Śiva and Śakti; or Puruṣa and Prakṛti.

A yogi, through the eight siddhis, attains a fractional power. However, the power of creation remains with Īśvara alone. The weft and weave of the cloth cannot negate it. How can the jīvas with their minds, identified with so many sheaths of Reality, deny the world when it cannot see the wellsprings of the world, the Brahman holding it aloft?

Summarizing Reconciliation and Non-Contradiction

Samanvaya (Reconciliation)

Advaita is absolute non-duality, and our interpretation should not make it a disguised duality. We must seamlessly reconcile the two statements that represent the final vision of Advaita:

- Brahman alone is real; all else is unreal.

- Brahman is That by knowing which all this is known.

How can we achieve samanvaya (reconciliation) and not virodha (contradiction) between them?

The dialectic, which does not deny the ALL, but denies the condition in which the ALL appears to be ELSE, provides the answer. For the ALL to be ELSE, it must stand in OTHERNESS from Brahman. The core of the negation lies in this otherness from Brahman. There is only Brahman and nothing else, and still there is no-thing that is actually denied, because the All that is denied as standing in otherness from Brahman is subsumed in the Oneness of Brahman.

Śaṅkara says in the commentary of the Chāndogya Upaniṣad: words and all things that are spoken of with THE IDEA OF THEIR BEING DIFFERENT FROM EXISTENCE are Existence only. Śaṅkara equates the false idea “that it is a snake” to the false idea “of the world being different from Existence”. The universe as Brahman is real; the idea that the universe stands independent of Brahman and is self-subsisting is unreal.

The Dialectic Of Material Causality

The locution where the unreality of the world arises cannot be considered in isolation from the Advaitika dialectic. For example, guṇa (attribute) is separate from dravya (substance) only through falsity and arises only through articulation of speech. Logically inexplicable, speech allows the false to be spoken. It is anirvacanīya because it arises through the self-referencing nature of Māyā. Neurosis of saṃsāra is the schism of being separate from the Self when in truth there is no separation. TThis explains why some schools refer to realization as 'union', while others refer to it as 'healing'.

Advaitika dialectic both affirms and negates the world. The effect (the world) is not different from the cause (Brahman). The seeming separateness has 'vācārambhaṇam' – speech for its origin. The truth is the identity of the effect with the cause, and the falsity is their separateness. The falseness is 'vikaraḥ', transformation, that is 'nāmadheyam', having its origin in name only. The effect, always pre-existent in the cause, undergoes no real transformation. It is the mystery of speech that generates the illusion of a changing generative world. Therefore, 'jaganmithyā' relates to the speech-generated pole of falsity. But the pole of truth is that the world, non-different from Brahman, is real only. It is due to this non-difference that the All is known when Brahman is known.

The Mystery of Vāk

Most (contemporary) interpretations ignore Advaita's philosophy of language to understand its dialectic. Śaṅkara mentions three important tenets:

- A word is eternal and is eternally connected to its object.

- A word denotes the sāmānya and not the viśeṣa.

- A particular (viśeṣa) is non-different from the universal (sāmānya).

These three in combination conclude that the difference of the effect from the cause arises due to the mystical difference in the conditions of speech. The evolution of names and forms (vivarta) is what the Vākyakāras call the staging of speech. The stages are parā-vāk, pashyantī-vāk, madhyamā-vāk, and vaikharī-vāk. They are the different stages of speech, and yet in each stage, the word and object of the word remain the same. A form is not a non-form because it is unmanifest. In the unmanifest state too, it is the same form that is manifest.

Difference is seen in the world of particulars. But a particular is the universal instantiated as a particular. The sāmānya is the fullness of the viśeṣa. Therefore, avidyā, the lack of knowledge, is the showing forth of the limitedness of the unlimited. This is Avacchedavāda (Bhāmati School of Advaita). Abhinavagupta, the great exponent of Advaita -Tantra in Kashmir Shaivism, uses the term 'apūrṇakhyāti' to express the same idea.

Vivartavāda and Non-Creation

Creation proceeds out of the ‘evolution’ (vivarta) of names and forms. ‘Creation’ is only the pre-existent in Brahman. Therefore, there is in truth no creation. What is always already born cannot be born again. This is Vivartavāda — the doctrine of non-creation. Only when we habitually attribute existence to an object's mere manifestation does it become transitory. In truth the existence of an object is eternal, and the predications of 'existence' and 'non-existence' point to the world of vyavahāra. False is the transitory nature of things rather than the things themselves.

The real persists in all the past, present and future eternally. The individual jīva in the world of ordinary affairs, however, does not perceive the world like this. As a concession to common sense, the universe is said to be non-existent before being evolved through name and form. The “no non-existence of anything anywhere" and “all is Brahman” are the unbroken visions of paramarthika-satya that are true for a Jñāni. Time (Māyā) is the agent that imbues objects with its own attribute of change. The Jñāni sees truly that nothing is born, and nothing dies.

The Nature of Brahman as Nirguṇa

Brahman is the formless Pure Knowledge. A form is not of its Knower, but the form that the Knower knows. The object of knowledge is not descriptive of knowledge itself. Brahman does not have the svarūpa (form) or guṇa (attribute) of anything It knows. Brahman is nirguṇa. Brahman is Pure Knowledge in which all forms are eternally present. Therefore the highest truth is that Brahman is nirguṇa, which is also purṇa (full) with knowledge. That is His omniscience. Nirguṇa Brahman is the sole reality. The All does not contradict the perfect formlessness, the perfect immutability, the perfect Oneness, and the sole reality of Brahman. This Brahman of the Vedas has to be known through the Divine Third Eye, or the Eye of Śiva. He who opens it is Śiva.

Avidyā and Adhyāsa

The unmanifest avidyā, or a lack of knowledge, and the manifest adhyāsa are two facets of the same non-thing. Adhyāsa is the superimposition that is contingent upon avidyā. Āvidyā is the unmanifest root from which false bhavas rise as many branches. The most primary is that all this is 'other' than Brahman. The 'otherness' of the world is superimposition, or adhyāsa. The avidyā known as mula-avidyā refers to concealment or lack of knowledge, while the bhava-rupas of avidyā are false notions. The latter is adhyāsa.

The object is known because we see it. Yet the object is not known because we have questions about it. This characteristic of worldly people generates questions and the sciences. But scientific explanations are untrue if they do not conform to the intrinsic natures of things. Any explanation that fixates us in the artefacts of our explanations as being the truth is false. When Advaita says that avidyā colours the world, it is not saying that the world itself is false. The eye of knowledge opens to see that the world is Brahman. The closure of the third eye is the sleep of saṃsāra.

The Real and The Unreal

The unreal is meaningless and cannot be pointed out like 'the son of a barren woman.' In Advaita, everything that has a name is real. There is a second type of 'unreality' characterised by loss of genuineness.It is a kind of sleep, the causal state of 'privation of knowledge', which carries the potency for superimposing false notions to things. It is this second meaning of the word 'unreal' that we find in the context of adhyāsa. The chart below makes it clearer.

In recent years, there has been an attempt to 'show' that bhāva-rūpa-avidyā is an aberration of Śāṅkara Advaita. The main worry is that allowing bhāva-rūpa-avidyā would mean allowing a real avidyā, and that a real avidyā would make moksha impossible and make the Advaita position impossible to defend.

Such an apprehension is ill-founded. Mūla-avidyā and bhāva-rūpa-avidyā are nothing but suṣupti and adhyāsa. While the attempt to purify Śāṅkara Advaita is commendable, the cleansing process unfortunately discards a significant portion of Śāṅkara Bhāṣya. Bhāva-rūpa-avidyā does not make Advaita vulnerable to the attacks of the Pūrvapakṣa because its very manifestation is parasitic upon Mūla-avidyā, which is no-thing.

In the vision of Truth, there is no privation of knowledge (avidyā), and hence there is no scope for superimposition. The pūrvapakṣa loses the weapon of a 'real' avidyā with which to attack Advaita because the causal state of avidyā is no-thing and bhāva-rūpa-avidyā too is not a thing but a wrinkle that cannot exist without this no-thing.

Avirodha (Non-Contradiction)

The Māyā Vada is a main objection against Advaita based on the premise that Advaita equates adhyāsa with the world. This objection collapses when it is seen that Advaita's world is real and that world-unreality is only the superimposition of Brahman's otherness.

Again, the allegation that Advaita injects an extra-Vaidika notion of superimposition or adhyāsa into the Vedānta sutras has no base. This is because adhyāsa is nothing but the no-thing of avidyā. An avidyā that is not equated to the world is common to all Vedantika schools. Therefore, the argument that Advaita is non-Vaidika in character is groundless. When the confusion regarding 'Māyā vāda' clears up, what remains are the real differences between Advaita and other schools of Vedānta. These differences ultimately reduce to the difference of 'difference'. Any difference between the world and its substratum is not sustainable and is false. The pratibimba (reflection) is always one with the bimba (object being reflected).

The samanvaya of Advaita is a perfect and immaculate non-duality of Brahman without necessitating anything being euphemistically called non-existent. There is no contradiction between statements of jaganmithyā and statements about the world being real because the former speaks about the falseness of adhyāsa and the latter about the truth of the identity of the world with Brahman. Again, there is no contradiction between the Advaita position that the world is “mithyā” (illusory) and the Advaita argument against the Buddhists that the world is real.

Advaita says that Brahman is the Self of the world. It is the sat (existence) giving to the world its reality. The Buddhists denying a substratum to the world regard the latter as a void, like the illusion of a firebrand. Śaṅkara argues that the world is not void but has a real substratum (Self) and is therefore not unreal. Regarding the argument for jaganamithyā, Śaṅkara says that the jīva, characterised by avidyā, affirms the world but sees the world bereft of its Self. Such a world (that is bereft of the Self) is unreal, and hence arises the expression of 'jaganmithyā'.

Samanvaya, or reconciliation, is that each of the above two is made conditional to a stated position. But unconditionally, the world is real because it has Brahman as its substratum. To an opponent’s doubt that the Self might be a product of something else, Śaṅkara explains in his Brahma Sutra Bhāṣyam:

Now, if even the Self be a product, then since nothing higher than the Self is heard of, all the products counting from space will be without a Self, just because the Self is itself a product. And this will give rise to nihilism.

Brahman and The World

In Viśiṣṭādvaita, the relationship between Brahman and the world is that of substance-attribute, and hence the world is the body of Brahman. In Dvaita, the relationship between Brahman and the world is that of independent-dependent existences. Brahman is the independently existing Bestower of dependent existence in the world. Another school of Vedānta expresses the relationship as acintya-bhedābheda (unthinkable-identity-and-difference).

Advaita does not subscribe to any of these doctrines. The world is one with Brahman, and no relationship can describe it. Śaṅkara says:

Brahman's relationship with anything cannot be grasped, It being outside the range of sense perception.

The mind cannot grasp the relationship between Brahman and the world, as it is not a relation. Nothing can fully express this wonder because it is already the relation-less unity in the expression of the world. This mystical nature is neither opposed to reason nor is it fully expressible by reason.

Concluding Remarks

Śrī Aurobindo, one of the most ignored intellectuals of modern India, and who arguably had the best grip on Indian culture, its traditions, and its philosophies, wrote in ‘The Life Divine’ -

The two are one: Spirit is the soul and reality of that which we sense as Matter; Matter is a form and body of that which we realise as Spirit… Matter also is Brahman and it is nothing other than or different from Brahman.

Advaita is indeed a razor’s edge. One may believe they have grasped the philosophy, but it can quickly elude them. As a metaphor (not to be taken too strictly), Advaita is to Nyāya-Vaiśeṣika what quantum physics is to Newtonian physics. In the solid world in front of us, it is Newtonian physics that rules, just as Nyāya-Vaiśeṣika explains the world around us. Nyāya is the basis of all our knowledge-seeking, debates, reasoning, logical systems, dharmaśāstras (the guides to living a proper life), and upavedas (the branches that discuss arts, music, sciences, engineering, and architecture).

Quantum mechanics gives a higher-order explanation of the world but without rejecting Newton. It subsumes the latter into a larger framework where the subsumed is not false. Advaita’s relation to Nyāya-Vaiśeṣika is something similar. The former subsumes the latter into a larger framework. Though both quantum physics and Advaita have a grander scale of explanatory power, it is also true that both are not understood properly even by their proponents fully. Feynman famously said, “I think I can safely say that nobody understands quantum mechanics.” Anyway, Advaita is the pinnacle of Indian philosophical systems, which have been enthusiastically taken up by people across India and the world, especially the new-age gurus, and yet it has been consistently misinterpreted.

As Śrī Chittaranjan Naik jī rues, the multiplicity of Advaitika traditions and their consistent disagreements on the interpretation of Śaṅkarācārya’s writings have abetted the confusion regarding some of its important ideas. In Nyāya-Vaiśeṣika, the perceiver (Ātman) and the perceived (world) exist as real entities. The point that Naik jī makes in the article is that, for Advaita, the world exists as a superimposition on the real Brahman. Brahman is ‘all’, and in this all, the world is also real. To say that the world is either completely non-existent or exists as an independent entity without a substratum is a falsity. It is this falsity which Advaita rejects.

Anyway, spiritual giants like Ramana Maharṣi or Śrī Aurobindo always insisted that reason and intellect are limited faculties when trying to gain Advaitika insights. Are the gods real? Ramana Maharṣi says in one of his talks that a vision of God is only a vision of Self objectified as the God of a particular faith. The Vedantika vision of Advaita does not dissolve the world of men or divine beings into nothing. It goes into the essence of all the experience and perceptions to realise that everything is Brahman only. Śrī Ramakrishna once said that an Advaitika seeker discovers first that the world is unreal and then later sees it as real. The real and yet unreal world is indeed perplexing.

In the Advaitika vision, the world never disappears. Ādi Śaṅkarācārya explains in his Brahma Sūtra Bhāṣya that the world is not annihilated like ghee with fire. The annihilation of the existing universe of manifestation is an impossible task for any man, and hence the instruction about its extirpation is meaningless. Even if it were possible, the first man to achieve liberation would have annihilated the universe. The first liberated person would have ensured that the present universe was devoid of any manifestation.

Hence, the realism of the world and its attributes is very much intact in Advaita. The negation is of the idea that the attributes of the world have an independent existence without a substratum of Brahman or the Self. As Śrī Chittaranjan Naik explains in his first book, ‘Natural Realism’, the oft-repeated criticism that Advaita’s position is that ‘nothing is real’ is a profound misunderstanding. The complete expression is brahma-satya, jagan-mithyā. The subject matter of Advaita is Brahman and not the world, and thus, jagan-mithyā is never an isolated proposition. The locution of jagan-mithyā (world illusion) is always with the locution of Brahma-satya (Brahman Reality).

A discussion of the world, excluding Brahman, however, makes it satya, or real. Denying the reality of the world, which excludes Brahman, reduces it to an unacceptable nihilism. Ādi Śaṅkarācārya takes the position that the world is real, refuting Vijñānavāda and other idealist schools of Buddhism that deny Brahman. Modern proponents of Advaita Vedānta overlook this vital point.

Naik jī further explains that the relation between Brahman and the world is the relation of Bimba-Pratibimba, the object and its reflection. There is a common misconception arising about the ontological (reality) status of the reflection seen in the mirror. The reflection, say of a flower, is unreal, but the object called ‘image of a flower’ is real. In other words, the object is not true to the name ‘flower’, but it is true to the name ‘image of a flower’. Each object in this world may be a reflection (pratibimbas) of Brahman, but they are true to their names. Hence, they are real. Their existences are entirely dependent on the Bimba, which is Brahman, the Supreme and Sole Independent Existence.

However, this vision is available to the highest of seekers. For the teeming ordinary mass of people, reason and intellect can only reach a certain height. The leap to the highest insights can only happen in the deepest contemplation when the mind dissolves and only the Witness remains and the insight happens intuitively that all is Brahman. The world, being nothing but Brahman, however, remains intact.

The original article series upon which this two-part summary series is based, can be found here.

li margin-bottom: 8px