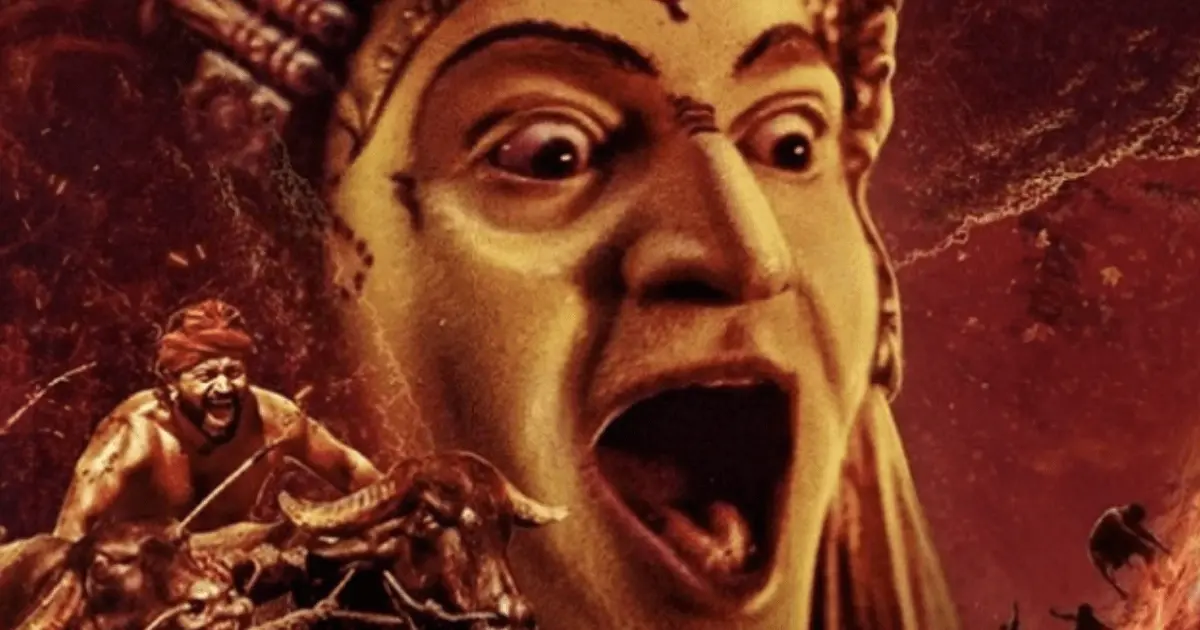

Kantara is a movie like no other, and for a reason. Kantara conjures magic at two levels: one where language plays a pivotal role in getting a grasp on the temporal aspect of the narrative. This facet of the movie transpired in the mind of its creator, Rishabh, who is a genius. Then there is the subliminal aspect, which is the undercurrent of the movie. This facet is felt and experienced because of the deity.

The Deity, whose power has unleashed this experience on us, has desired to do so.

Kantara begins with a quest of a king who is blessed abundantly with everything, material wealth and familial health. What more does one need than this in life? Yet discontentment haunts him and his quest lands him up at the threshold of Divine presence in the distant forest in what can only be termed as ‘divine discontent’. In this Divine presence the king finds fatherly and motherly warmth.

Panjurali and Guliga (kṣetrapāla) are the grāma devatās of the forest dwellers. The wealthy landlord expresses desire to take the Deity along with him. Deity speaks through the phenomenon of āveśa and asks him what will you give the villagers in return? Thus the Deity screams out loud, and commands the landlord to know until where this voice has reached and gift away that quantum of land to the forest dwellers. Landlord keeps his promise and takes the Deity home, and is blessed with peace and prosperity.

Two generations down the lane, his grandson living in a big city comes back to claim the donated land from the villagers. His father prevents him from committing this mistake, as what has been donated doesn’t belong to them anymore. But the fool doesn’t pay heed. On the occasion of a sacred ritual night of daiva ārādhane/ bhūta kolam, the arrogant heir asks the Deity to return the land, and Deity then poses the most poignant question;

“What has been offered by the human can be returned, but the peace that has been bestowed upon your family by the Deity, can you return that?”

The arrogant heir tells his father that when he gets back the land via a court dispute, their material prosperity would multiply and peace and contentment would inevitably follow thereafter. The Deity laughs at this irredeemable ignorance, and tells this arrogant fellow:

“I will decide the outcome of this case on the stairs of the court, this shall not be decided by humans sitting in the courtroom”.

The grandson then arrogantly questions the authenticity of the whole ritual process and insultingly asks “are these words being spoken by the Deity or by the one who has adorned the costume of the Deity?” The Deity smiles at this ignorant question and turns to the flame and utters “if it is the one who is wearing the costume of the Deity who speaks these words, then you will find that person, if these words come from Deity, may you never find the Deity.” Saying this, the Deity holds the flame in his hands and runs into the jungle and simply vanishes in the forest. Appearance and disappearance of the flame/ light set the tone for the mystical nature of the forest. Word Kantara has the word kāntī in it which means “mystical flame in the forest”. This now becomes the archetypal truth.

This sets forth the momentum of Karma. Just as humans would have kārmic connection not only with other individuals, or a collective of humans, we have kārmic connection with our ancestors and deities too.

The arrogant heir meets his death on the stairs of the courtroom, as decided by the Deity. Now, the father of the hero is the ritual performer who runs into the forest as the Deity and vanishes. His mother is now a widow. After personally witnessing this disappearance, the protagonist is scarred for life and refuses to take up the role of a ritual performer. He doesn’t have any animosity towards the Deity, he is simply afraid.

Here, let me address a question that I came across, “Why would Deity leave its devotees widowed?” Death is inevitable. One may die due to old age, disease, accident and countless other ways. Of those countless ways, there could be departures caused by the Deity. That is simply karma and this option of departure is not available for all, but only to those who serve the Deity. So if we were to pose this question to those who serve this Deity incessantly, “Oh brother, what sort of death do you prefer? Do you want to depart due to disease, accident etc., or by the will of Deity? “What is the likelihood of choosing to depart with the will of the Deity? Isn’t that the most meaningful departure for the one who has served the Deity all their life!

Many people seemed to have thought that this film is nothing but a good ritual opening scene and splendid ritual climax. But the whole story when closely observed is nothing but the Deity’s will in shaping the circumstances that lead to the climax.

The character of the protagonist, Shiva, is a superbly conceptualized one. It is his destiny to take his father’s position eventually as the Bhūta Kola performer. Something in him very well knows the ramifications of this responsibility. The Deity transpires all circumstances to lead to this eventuality. His repeated nightmares can be explained in simple terms as calls of his destiny.

His character has two key facets: a reckless and fearless vagabond but one who is deeply invested in protecting his community, the aspect of kṣetrapāla (Guliga). It is this context that draws out numerous scenes of him protecting his village from antagonists. He comes across as alcoholic, but those who understand the Bhairava upāsanā, will have no problem with this. For numerous scenes where alcohol is involved one can observe, it sharpens his awareness and he starts sensing things which are otherwise inaccessible to the normal consciousness. This by the way is not the same outcome for his actual alcoholic friends. There is even what appears like a casual scene where the villain says, “this guy needs stronger alcohol, imported brands will not cause any intoxication to this fellow”. Add to this is his element of smoking pot. That completes the picture of him as a Bhairava figure.

The climax scene is the possession of the hero by Guliga (kṣetrapāla). For the possession to be complete two things need to happen. Firstly, a balī is a must for the invocation of kṣetrapāla. That happens when he is thrown onto the sacred stone of Guliga and blood of the hero splatters on the stone. Thus the need for balī is achieved. Second aspect is more nuanced. Though the protagonist is blessed to inherit the place of the ritual performer, he has to overcome fears he has cultivated from his childhood. So he needs to die, rather the Self which experiences fear needs to die, thus he experiences near death. And when the main deity resuscitates him, the one who wakes up is not the same person anymore, now he has the āveśa of Guliga (kṣetrapāla), who beheads the villain and closes the karmic cycle with the landlord family. Thus we never get to see the character of the Shiva anymore.

Elements of the Ritual

The rituals used in the movie are very accurate and stay true to their original form. Bhūta arādhane rituals are similar to Theyyam, Mudiyettu etc. They need a little in-depth analysis. Immense amount of time is taken in preparing the ritual performer. The ritual performer undertakes a specific diet or no diet, before the ritual. In general they have to live a life which is codified in a specific way. The costume and ornaments play a pivotal role. That’s why in Kantara ornaments and āyudhas emerge at various points in slowly developing the story line thus announcing the return of the Deity. Of the ornaments the title of Kantara is adorned by a special anklet. The anklet and the sound associated with it have a most special place in the story. That is why we can see the ritual performer walking before the ritual with the anklet in his hands and people offering their salutations to the Deity by paying their respects to the anklet.

These small moments were deeply powerful moments for me, as they create a complete psychological ambience. Yet another important moment of gradual build up of Deity into the body of ritual performer is when the makeup is completed, the performer is made to sit, eyes closed, and made to open the eyes in front of a mirror. Something of the Deity enters him at that very moment. The more the Deity takes over the abode of the human body, the more the self effacement it causes of the ordinary persona. One can observe a neutral yet powerful face. The smile that adorns this face seems other worldly. Accompanying music, which has specific drum beats, is an ancient method that cuts across diverse cultures where this ritual plays a central role. Rhythms literally start opening up the lower chakras of the performer and allows for the buildup of the śakti. The Deity then latches on to this śakti. Handing over the flame/ fire torch to the performer brings in an element of unfathomable power to the Deity. In this peak mood of the Deity, bhoga/ ritual food needs to be offered. In the climax fight scene, this facet is made adequately clear. When Guliga holds the torch and waves it for himself, it is followed by the partaking of the puffed rice.

Those who know these rituals, and are familiar with the visceral energy that operates during this āveśa, can easily spot what an impossible feat has been achieved by the creators of Kantara. It is one thing to make this happen on the ritual platform and almost impossible to recreate that on the screen. This can be done only when there is consent of the Deity. The universal effect for most sections of the audience seems to be silence. The audience is stunned into silence.

The reach that the movie has achieved is only due to the Deity’s will. There are many fascinating interviews of the crew members of the film with interesting experiences, even to those who are otherwise agnostic of this experience and world view. It is a clear indicator of the divine will behind the movie.

You will have no doubt about this when you watch it, what will remain is one of the greatest climactic moments for a long time to come on the Indian cinema screen. For the Deity transmits śakti into us, through surreal acting of the protagonist, thus binding us in raptures. The character of the protagonist simply evaporates and transmutes into the Deity.

Every frame of this movie is throbbing with life, full of matchless vernacular wit. It is true that the Kannada speaking audience is at a distinct advantage. Even in the middle of the most poignant moments in the narrative, the writing hurls us into realms of unexpected humor.

Frame one starts in this mystical forest and the narrative never leaves its ambience even for one moment for almost three hours.

Thus this forest, where the Deity resides, is itself personified as a being.

State vs. class vs. caste vs. rooted cultures, all conflicts are addressed with such dexterity. However they are not central to the narrative. But what is central right from the beginning till the end is the Deity. The movie talks about people who believe in the wisdom of this Deity. About the people whose body becomes an abode for the Deity to communicate the saṇkalpa. We feel totally nourished to partake in this offering, and at times we are humbled about the fact that we are somehow connected to this culture, this land, these relationships with our guarding forces. The ultimate gift that Kantara hands over to us, is the sublime reminder about our connections to our deities.

Have no doubt; the deities are waking us up to their presence like never before. They are willing to travel from their forests, kśetras onto the screen and talk to us, to tell us: “Oh children, don’t remain blind anymore to our presence. Take refuge in us. We are here with you every moment.”