This article is Part 8 of a series of articles on Eastern Philosophy. Read the previous installments here:

The individual articles in this series are written so that they are self contained; but, occasionally may refer to older articles for some details.

Last time in Part 7, we saw the Hindu dualist school of Sāṅkhya. We also saw a brief overview of Buddhism, its early history, and the Mādhyamaka school of Mahāyāna Buddhism. In this article, we will look at a detailed picture of the intellectual history of early Indian Buddhism; and then proceed to learn about a peculiar Buddhist school of philosophy called the Sarvāstivāda Vaibhāṣika school which subscribes to a notion of permanence to explain the impermanence of the observed reality! It also shares some similarity to the Sāṅkhya school that we saw in Part 7, which is why we cover it here. In this school too, there is some eternality in causation, as you will see.

The Proliferation of Early Buddhist Schools and Texts

A few months after the Buddha’s death around 483 BCE, his followers who constituted the Saṅgha convened at Rājagṛha and had the First Buddhist Council. It was here that the Buddha’s disciple Ānanda recited the orally memorized teachings of the Buddha and another disciple Upāli recited the orally memorized rules for the monks. Eventually, these orally transmitted messages would crystallize into two of the three types of Buddhist texts (called the tripiṭaka) after being written down:

- Vinaya - the collections of monastic rules of conduct.

- Sūtra - the collection of the Buddha’s teachings.

- Abhidharma - expansion and philosophical systematization around Buddha’s teachings, of which these literature came around later.

But as time went by, very soon, disagreements began to emerge within the Saṅgha. Around a century after the Buddha’s death (around 383 BCE), when the Second Buddhist Council convened at Vaiśālī, the Saṅgha had its first schism. This was not so much due to doctrinal differences but due to differences in the rules of conduct. During this first schism, a group constituting the majority of the Saṅgha members split up to form a splinter group named the Mahāsaṅghika. The conservative elders of the Saṅgha who constituted the minority, split to form a separate group that came to be known as the Sthaviras which literally means elders in Saṃskṛta. The Emperor Aśoka convened the Third Buddhist Council around 250 BCE which was held at Pāṭaliputra under his supervision during which he decided to bestow his favor on the Sthavira sect (the way of the elders). Aśoka’s missionaries spread this school, one branch of which would soon develop into the Theravāda school that is now dominant in Sri Lanka. But as time went further, only more schisms happened within the Saṅgha. Note that these later schisms did not happen so much due to differences in doctrine but because of the fact that the Saṅgha was becoming too large in numerical strength and too widely distributed across geography so that homogeneity was no longer possible to maintain. Thus, different interpretations of the Buddha’s teachings came to develop at different places. We get from a source text that Buddhism split into 18 schools as time went by. Out of them, the tripiṭaka canon of only two schools survive in full. One is of course the Theravāda school, whose canon written originally in Pali survives as the collection of sacred texts of the Theravāda school. The full canon of another school named Sarvāstivāda school (the focus of this article) does not survive in its Saṃskṛta original in its entirety, but is fully preserved in Chinese and Tibetan translations. From the other schools, we either have no surviving texts at all or just a subset of the texts surviving in either Saṃskṛta, Chinese or Tibetan languages.

Eventually, around the 1st centuries BCE-CE, a group of anonymous sūtras of mysterious origins in Saṃskṛta attributed to the Buddha started circulating in India which offered a different view of the Buddha and Buddhism. Some monks began to accept these teachings, and eventually their overall acceptance increased. In these texts, the Buddha was not merely seen as a great man who found the path to enlightenment - but he became a god to whom one could pray to and worship as well. There arose the concept of a Bodhisattva - a being who attained enlightenment but out of compassion, did not go to nirvāṇa but stayed on in the universe until all souls would be freed from saṃsāra. In this path, enlightenment in this life could be accessible to everyone - not just monks. This was possible due to the compassion of the Bodhisattvas. Hence the schools of Buddhism based on these texts came to be known as Mahāyāna (Saṃskṛta: Greater Vehicle) Buddhism - the vehicle that can carry a greater number of peoples across the ocean of saṃsāra.

And how could these newer sūtras claim to be authoritative? Its followers claimed that these teachings were the higher secret teachings of the Buddha given to his innermost group of disciples while the ordinary monks got the Theravāda teachings. The secret teachings were claimed to be hidden (in caves or heavens or underwater palaces - depending on the text!) for centuries, till the present age when they could be revealed. It was also claimed that while the ordinary teachings were heard and preserved by the disciple Ānanda, these secret higher teachings were heard and preserved by celestial beings and Bodhisattvas who were now revealing that again. The Buddha in some of these texts is said to have achieved enlightenment eons ago, but due to infinite compassion, he incarnated as a prince in the sixth century BCE and pretended to be in illusion, and finally pretended to have achieved enlightenment for the first time for the sake of benefit of others. This Mahāyānis began to call all the Buddhist schools that came before them as Hīnayāna(Saṃskṛta: The Lesser Vehicle) as they provided enlightenment only to monks. Lots of Mahāyāna sūtras proliferated over the centuries; and hence, the entire body of scriptures did not form a perfectly coherent doctrine, and even had contradictory teachings. So, each Mahāyāna school began to focus on a particular sūtra and build its philosophy by commenting on it - this would happen in India as well as in China, Japan, and Tibet.

Dharma & Conventional vs Absolute Truths in Buddhism

Many schools of Buddhism (excepting Theravāda) distinguish two types of being/existence/truth. Note that although the Saṃskṛta words sat/satya literally derive from the present participle of the verb “as = to be”, they also have a connotation of truth because Indian philosophy equates truth to existence in a metaphysical context. Hence, the translation of sat or satya as being, existence, truth, or reality. The two types of sat in non-Theravāda Buddhist school are:

- dravya sat / paramārtha sat (substantive / transcendental / absolute sat)

- saṃvṛti sat / prajñāpti sat (conventional sat)

What is the difference between these two levels of existence or being? Entities that exist substantively or absolutely (paramārtha satya) possess what in Saṃskṛta is called as svabhāva. This Saṃskṛta word can’t be translated exactly into English, and hence deserves an elucidation. A difficulty is the fact that the concept of svabhāva does not have any straightforward equivalent among the concepts discussed in Western philosophy. This is not to say that it is a fundamentally alien concept to the West, but merely that the Indian term svabhāva combines a number of notions which are regarded as distinct in the Western philosophical tradition. Thus, I will never translate this word and will simply use it in its Saṃskṛta original.

Literally at an etymological level, the word splits up into two parts - sva (self/own) + bhāva (existence). It has been translated into English as “essence”, “inherent/independent existence”, “own being”, “intrinsic nature” or “substance” depending on the context, because it indeed actually can mean all of the above notions. The underlying idea is that something has existence (bhāva) all on its own - independent of anything else. On the other hand, if an entity has only conventional being, it means that it depends on other entities for its existence and hence lacks independent existence (svabhāva).

One way in which an entity can lack svabhāva is by being spatially extant; i.e. being composite and made up of parts.

A chariot lacks svabhāva because its existence depends on the existence of its parts. So, a chariot cannot exist on its own - independent of anything else. It is divisible into its parts; and hence, it is only its parts that can have svabhāva. The chariot is only conventionally real - a conventional name given to an aggregate of a certain combination of its parts. Now we can also keep dividing each part of the chariot further; and we will ultimately end up with entities that are indivisible further - if we are to avoid an infinite regress, which Buddhism wants to. The ancients did not know of the fundamental indivisible particles of modern physics like quarks, leptons, and gluons. Hence they followed the four element model - that all material substances are combinations of four kinds of indivisible elements - earth, water, fire, air. So, instead of quarks or leptons, they use fire-atom or water-atom as examples of the fundamental indivisible elements that constitute all material reality. Do these fundamental particles at least have substantive independent existence (while their aggregates that we perceive have only conventional existence)?

Yes. But there is an extra twist:

According to Buddhism, an entity can also lack svabhāva by existing for an extended duration of time.

One can split a chariot into its parts and end up with quarks or gluons. But Buddhism goes one step further, about which we already saw in Part 5.

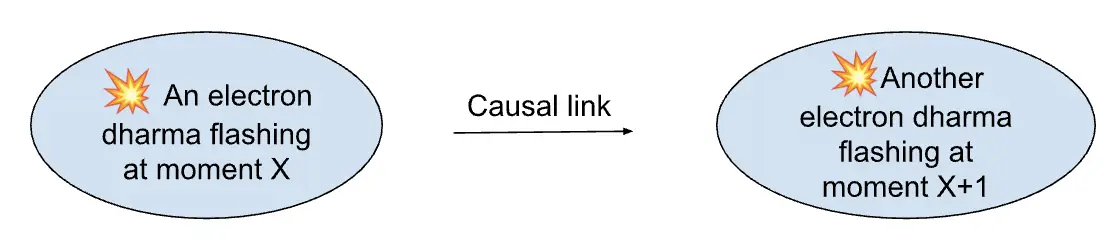

In case you haven’t read Part 5 or don’t recall: We split the chariot into its constituent indivisible particles in the previous exercise above. These particles too, according to Buddhism, can be divided across time into their constituent moments. A single photon living from 1:00 pm to 1:15 pm can be further split into “photon at 1:00pm”, “photon at 1:01 pm”, “photon at 1:02 pm” ,... and so on at every moment of time. So, it is not just the elementary particles but the elementary particles at each moment of time that are considered indivisible according to Buddhism. Such an indivisible momentarily existing unit is what are called as dharmas in Buddhism. This follows directly from the anti-substance metaphysics that is shared by all schools of Buddhism. Ordinary metaphysics is based on enduring substances undergoing change. We think of fundamental particles, for example, as enduring across time and existing in extended time. But in Buddhism, an apple or an electron at the previous instant is not the same thing as the apple or electron at this instant. They are causally connected but not identical. It is the mind that imposes the notion of identity between the apple/electron at the previous instant and the apple/electron at this instant due to causal connection. It is the mind that says something along the lines of -

H*ey, this is the same apple/electron at different times…*

It is the mind that imposes an identity of substance over what is in reality, only a causal flux. According to Buddhism, “the electron at moment X” and “the electron at the next moment X+1” are not the same, but only causally connected - the former electron at moment X disappears to produce another electron at X+1. There is no such thing as a single apple or a single electron that exists across an extended duration of time. There is only a red blob at one instant giving rise to a red blob at the next instant. Similarly, there is no such thing as an electron that exists across an extended duration of time. There is only a lump of charge “-e” and mass “m_e” at one instant giving rise to a lump of the same charge “-e” and mass “m_e” at the next following instant. That these red blobs, at all these different instants correspond to a single same substance, (called “apple”) is simply our hypothesis. Similarly, these lump of negative charges of charge “-e” and mass “m_e” at all these different instants correspond to a single electron enduring in time is also our hypothesis! This is the concept of Buddhist impermanence (anitya). Just as a chariot is denied independent existence by splitting it into its parts, an indivisible particle too is split across time into its individual instantiations and only has momentary existence. Everything that is observed composite in both space and time are split into their constituent spatial parts or their temporal parts. Only the momentary indivisible units have svabhāva. Such momentary elementary units of reality are what are referred to as dharmas in Buddhism.

So, dharmas in Buddhism are not like atoms but more like atomic events. But since dharmas also encompass mental phenomena, they can be said to be psycho-physical elementary events like an electron at a given instant or a momentary flash of intention. What we commonly think of as a single electron (or a fire atom) existing for an extended duration is decomposed into a series of sequentially following causally linked flashes of electron events (events of fire-ness). The electron event at moment X+1 is not identical to the one at X although the latter derives from the former by being the effect of the former which serves as its cause.

Since ancient Indians did not know about modern particle physics, they proposed that material matter was made up of just four types of momentary dharmas - earth, water, fire, air. But there are other types of non-physical dharmas. Some of them are mental and some of them are structural. For example, about 75 such types of dharmas are mentioned in a text called Abhidharmakośa. For the complete list, refer to the appendix at the end of this article. For example, one such dharma is form (rūpa). Anything is an aggregate of its parts but it is not a mere aggregate of its parts. For example, two isolated atoms of oxygen are different from a molecule of oxygen even though both have the same two atoms of oxygen as its constituents. The difference is the internal structure (in this case, covalent bonding between atoms) that is captured by a dharma like rūpa. Of course, a particular structure or concept like the covalent bond can’t be independently perceived, without any material basis (in this case, atoms), but the abstract idea of a form (rūpa) is an indivisible and irreducible aspect of reality. See the full list of dharmas in the appendix to know more. The exact number and constituents of the dharma list varies in different texts, but what is important is the underlying motivation and logic of the list.

Note: In Hinduism, the word dharma has many meanings, as is well known. To only add to this confusion, Buddhism gives us two more additional senses of meaning. Initially, the word dharma in Buddhism referred to any teachings of the Buddha. Later, as the abhidharmas proliferated as a result of Buddhist philosophers analyzing reductively the types of indivisible elements of reality, the word dharma came to stand for a type of such an irreducible element of reality - like a fire-dharma, or water-dharma (reminder again that dharmas have momentary existence in Buddhism).

From ‘An Introduction to Indian Philosophy’ by Bina Gupta -

Reality is a series of instantaneous events; there is no permanent substance, just as there is no universal (sāmānya) instantiated in a class of particulars. There is only similarity between momentary events, but—mistaking similarity for identity—we regard similar particulars as possessing an identical feature in common. The illusion is sustained when we give particulars the same name (“jar,” “tree,” “river”). The identity of a name together with the resemblance among particulars creates the illusion of real universals.

Buddhist Abhidharma Texts

We saw that the sūtras and the vinayas grew out of orally preserved teachings of the Buddha. We saw in Part 2 that the Buddha refused to answer abstract metaphysical questions; as he thought that attempting to answer them will only make one’s clinging more, and only sink us further into saṃsāra - and that the only important thing for nirvāṇa was right ethical conduct and detachment by meditation. The Buddha wanted his disciples to be completely pragmatic, and do what they should to attain enlightenment rather than discussing abstract theories that have no relevance in life. But, the very same reluctance and silence of the Buddha with regards to metaphysical questions came to be interpreted in different ways by his later disciples. These disciples thought that the Buddha was silent on these metaphysical questions only because the state of nirvāṇa which was attained by cessation of the activities of senses, could hence not be described by any categories which could be put in words. Hence, the disciples eventually began to think that upon attaining nirvāṇa, the Buddha entered a new state of reality that was mystical and transcendental (since it was beyond the senses and indescribable by any sense experiences that are encoded by language). Ironically, these grounds led many followers of Buddha to a development of systematic philosophical thoughts about a transcendental reality.

It is funny that the primarily ethical and anti-philosophical teachings of the Buddha, through his mere silence on philosophical matters, led to dozens of philosophical schools of Buddhism after his time. This development is what began in the third part of the Buddhist canon - the abhidharma.

From around the third century BCE onwards, a new group of texts called the abhidharma (Saṃskṛta: abhi= about) texts began to circulate. They originally began as lists of entities that would serve as memory aids for remembering Buddhist teachings which are referred to as mātṛkās (matrices). You might have noticed already that Buddhism loves putting up lists (the 4 Noble Truths, the 8-fold way, the 12-fold cycle of dependent origination, which we saw in Part 2). Then, commentaries began to build around these matrices which eventually became systematic philosophies built around the analysis of the dharmas. It is in this abhidharma collection where different Buddhist sects differ the most.

The Sarvāstivāda Abhidharma School

The name Sarvāstivāda is derived from Saṃskṛta, with **sarva** meaning everything and “astimeaningexists,translating tothe doctrine that everything exists. This reflects its central tenet that **the momentary dharmas**, the fundamental elements of existence, exist in the past, present, and future. An alternative name, **Hetuvāda**, meaning “school which expounds on causality which reflects its emphasis on analyzing causal relationships which we will see soon. The Sarvāstivāda school split into two sects eventually - the Vaibhāṣika and the Sautrāntika.

In this article, we will focus on the Vaibhāṣika sect first and then mention the points where the Sautrāntika differs.

- The Vaibhāṣika school is named so because it follows the large commentary (mahāvibhāṣa) on an important abhidharma text named Jñānaprasthāna attributed to Kātyāyanīputra and probably composed during the first to third century after the Buddha’s death. Originally from Kashmir, some of the important teachers of this school were Dharmatrāta, Ghoṣaka, Vasumitra, and Buddhadeva.

- The Sautrāntika school is called so because they accept the authority of only the sūtras and traditionally is said to be founded by Kumāralāta of Takṣaśilā. The main literature of this school seems to have been lost, and our knowledge of it mostly comes from its opponents trying to refute them. A main source of information about this school is from the text named Abhidharmakośa written by a monk named Vasubandhu who was a Sautrāntika initially, but converted to a Mahāyāna school later in his life, writing the book to refute his previously held positions.

The Vaibhāṣika Metaphysics: Reality and Temporal Causation

The Vaibhāṣika school fundamentally agrees with the momentary nature of dharmas. But somewhat unintuitively, it postulates that the momentary dharmas at all moments - past, present, and future - exist. Hence, the name sarva (everything) + asti (exist) vāda. So, a dharma existing at this present moment, does not vanish out of existence, after this moment becomes past. Also, a dharma that will exist at the next moment (in future), does not suddenly come into existence at the next moment, after this present moment passes by and its next moment becomes present. So, all dharmas at all moments are always real!

There is an important philosophical problem with the above position because the Vaibhāṣikas are trying to combine two seemingly incompatible positions: On the one hand, they accept the standard Buddhist doctrine that nothing is eternal, that all reality (dharmas) is momentary; on the other hand, they make every moment eternal; inasmuch as each dharma, the past and the future, like the present, is or exists. If all dharmas exist, then what is the difference between the dharmas of present moments and the dharmas of past and future moments? There must indeed be a crucial difference - because only the present glass of water can quench thirst and not future or past water.

The Sarvāstivāda accounts for this by the theory of ‘efficacy’ (kāritrā). Even though past and future dharmas all exist, only the present dharmas possess efficacy, and for this reason they are able to perform functions that past and future dharmas cannot. The electron dharma that we happen to see at this present moment is just basically that eternally existent electron dharma (that was destined for this moment) exhibiting momentary activity or efficacy (kāritra) at the present moment. A dharma is present because it is manifesting its causal efficiency or activity (kāritra) for that single brief moment (in an appropriate context of other flashes of other dharmas). After the moment passes, its activity ceases and it returns to its original inert condition. We may think of the dharmas as they are in themselves as occupying another dimension of reality, from which they briefly migrate into our world, flash for a moment with activity, and to which homeland they return. That actualization or activity, the temporal presence of the dharmas in and as our world, is the exercise of their efficacy in a causal complex unfolding moment by moment. Intrinsic natures of dharmas are fixed (dharma-svabhāva is nitya), but the exercise of their efficacy or activity (kāritra) is momentary (anitya) and circumstantial (kādācitka). The Vaibhāṣikas think that it was to these momentary discharges of energy in the world of conditioned phenomena that the Buddha was referring when he spoke of universal impermanence.

The exercise of efficacy when a dharma enters a causal complex is not a change in that dharma, but just its manifesting what it permanently is. Each case of momentary actualization or activity lasts just long enough to bring about its own following moment. A dharma normally attracts the manifestation of another token of its own type. This explains the perceived stability and continuity. An electron dharma flashing at one moment at one place normally attracts the flash of another electron dharma at the next moment at a nearby place, which we perceive conventionally as “the same electron existing at both the moments which has moved from one place to another nearby place”. The sequence of what dharma has to be active at what moment has already been determined and is just actualized when the activities of dharmas play out in real time. A dharma is said to be conditioned (saṃskṛta) when it participates in this causal complex. ‘Conditioned’ means having the four characteristics of origination, duration, decline and impermanence.

The moment of manifestation is what is called the present time. Future dharmas are those that have not manifested their proper function. Past dharmas are those that have. The dharmas do not just exist at those times but rather constitute them – time means the actualization of dharmas. They actualize into worldly existence “as” those times. Time is understood in terms of the exercise of efficacy. Time is not a substantial reality independent of subjects, objects and events. The dharmas do not ‘pass through’ time as though time were a separate reality. Our experience of temporal flow is in fact the replacement of dharmic efficacies. A moment of time is simply characterized by the set of all dharmas that are active. There is no real change on the level of the primary realities - the dharmas though destined to be active at a given moment, exist timelessly and immutably.

It is these dharmas as they are in themselves that are held to exist in the ‘three times’: future, present and past. The impermanence taught by the Buddha refers not to the dharmas or their nature (they are timeless essences) but to their actualizations in causal complexes of this world. It refers to the momentary exercise of efficacy, here and now. The insubstantiality taught by the Buddha refers to complexes, aggregates and processes, and not to the dharmic elements themselves. The Sarvāstivādins thus taught that the impermanence taught by the Buddha more precisely refers to the functioning, and not to the essential natures of the basic dharmas.

But wait a minute! Does this look substantial - especially with eternal existence of dharmas with fixed svabhāvas being the permanent ground or source for all the dharmic-flashes occurring in the universe? Yes! That was the complaint of the other Buddhist schools to the Vaibhāṣikas.

Hence, to this school, time is not a separate reality by itself. The sequence of changing manifestations of kāritra is what gives us the feeling of time passing. Time is not a substantial reality independent of subject, object, and events. This is remarkably consistent with the theory of relativity.

The Laser Show Analogy

To give an analogy - consider all the momentary dharmas as an interconnected electronic circuit of laser bulbs, with their flashing ON as their activity and their colors as their svabhāvas. Also, for an accurate analogy with the dharmas, imagine that a light bulb, after being switched ON and glowing for a moment, switches itself OFF after the moment passes due to overheating its fuse so that a bulb once gotten a chance to glow at one moment, can never glow at any other moment (this is because a dharma is always momentary by definition and always belongs to a single particular moment only).

Now, consider a laser show that involves flashing of various lights from this circuit of bulbs serially in a fixed pattern so that the mixing of the lights from all the bulbs that are ON, create various shapes which when shifting moment by moment, creates a continuous video show. Somebody has already hard wired and hard coded into the circuit, the sequence of the switching ON of the bulbs that is to be followed for the entire show. Someone has already designed the circuit such that at the first moment, the following light bulbs should be ON, and that the switching ON of those light bulbs at the first moment automatically triggers the switching ON of some other selected bulbs near to them at the second moment, after their own switching OFF from their fuse overloads, and so on.

According to the Vaibhāṣika school, all of reality is a laser show of dharmas. The dharmas exist at all times in the same way that the bulb exists at all times. The inherent svabhāva of a dharma is fixed in the same way that the color of light that any given bulb will give when glowing, is fixed. It is only the causal activity of the dharma that is momentary in the same way that the glow of a bulb in this laser show is designed to be momentary. The activity of a given dharma at a given moment automatically triggers the activity of another set of dharmas at the next moment due to causal efficacy (in the natural laws of causation) in the way that the glow of a given bulb at a given moment is hardcoded in the circuit to automatically trigger the glow of another set of bulbs at its next moment (through the hardware of the circuit). The present moment is characterized by the set of all bulbs glowing or the set of all dharmas that are causally efficacious. The changing patterns of glow successively is what creates the flow of time.

A reality that is past has ceased to function due to impermanence. A reality that is future has not yet exercised its function. A reality that is present has originated and not yet ceased. When basic realities (dharmas) exercise efficacy, this is called the present. If dharmas do not yet exercise it, this is called the future. If efficacy has gone, this is called the past. Abhidharmakośa-bhāṣya 1.20

So the Vaibhāṣika picture is one of a giant causal flux, but with no real explanation of the intrinsic natures of the entities related in the flux.

We shall return to this point in a future installment of this series.

Epistemological and Ethical Motivation

Why propose such a counter-intuitive theory that the past, present, and future dharmas too exist? This is because of the ethical and epistemological convictions of the school. Ironically, the two reasons that the school gives for an intuitive notion of existence of past and future dharmas, are actually very common sensical notions.

Realism: The Vaibhāṣikas believe that all perceptions should correspond directly to objects of reality. This school does not allow any sort of representationalism in perception where the cognizance of a past object is just a stored representation of the past object in present memory. We directly perceive external objects as they are. This is like the direct, common-sense realism in Western philosophy, according to which - the book that I see, is itself, the book which is an object that is in front of me. My mind directly knows the external world. How about cases where we indirectly infer the presence of external objects - like when we infer fire from seeing the smoke? We infer fire upon seeing the smoke because in the past we have perceived smoke and fire together. One who has never perceived a fire would not be able to infer fire upon seeing smoke coming out of a building. The world is real; it exists independently of our knowledge and perception of it. There is no distinction between the world as it is and as it appears to us. Since all objects of perception ultimately must correspond to really existent external objects, and since we can think about past objects and have expectations about future objects, they must exist too.

Past and future dharmas exist because cognitions need real objects. When there is an object, there arises a cognition. When there is no object, there arises no cognition. If past and future dharmas did not exist, there would be cognitions whose objective grounds (ālambana) would be unreal things. Therefore there would be no cognition of the past and future because of the absence of objective grounds. If the past were non-existent, how could there be future effects of good and bad actions? For at the time when the effect arises, the efficient cause of its actualisation (vipāka-hetu) would no longer exist. That is why the Vaibhāṣikas hold that past and future exist. Abhidharmakośa-bhāṣya 5.25ab

Another motivation for assuming their metaphysical position is ethical. Some dharmas do not yield their effects immediately. For example, stealing does not necessarily instantly lead to a bad future state according to the notion of karma. So, if the stealing dharma no longer exists by the time its effects come to fruition, then how can it cause its fruit in the remote future?

Summary of the Vaibhāṣika School

- Everything (every dharma) exists - mental and physical; this includes the past, present, and the future as well.

- We directly perceive the external world.

- Reality is a series of instantaneous events (to exist is to be causally efficacious).

- The inner self too consists of a series of changing particulars.

- There is no permanent substance that persists with time; there is no universal (sāmānya) that is instantiated through its particulars.

- Basic substantial constituents called “dharmas” are real and eternal. But their exercise of causal efficacy is momentary (anitya) and circumstantial (kadācitka). A dharma is present if it is active (possess kāritra).

- Seventy five dharmas as per Abhidharmakośa - 72 phenomenal dharmas conditioned by ignorance and 3 unconditioned dharmas that are not defiled by ignorance.

- There is a real transformation of the conditioned into the unconditioned through insight.

Appendix

List of 75 Non-material Dharma Types

72 Conditioned (Saṃskṛta) Dharmas

Senses

- Eye - cakṣu

- Ear - śrotra

- Nose - ghrāṇa

- Tongue - jihvā

- Body - kāya

Sense objects

- Form - rūpa

- Sound - śabda

- Odors - gandha

- Taste - rasa

- Touch - sparṣṭvaya

- A sense object with no manifestation - avjiñāpti rūpa

- Mind - citta

Concomitant Mental Faculties - General Functions

- Feeling - vedanā

- Discrimination - samjñā

- Intention - cetana

- Contact - sparśa

- Aspiration - chanda

- Intellect - prajñā/ mati

- Memory - smṛti

- Attention - manasikāra

- Decision - abhimokṣa

- Concentration - samādhi

Concomitant Mental Faculties - General Functions of Good

- Faith - śraddhā

- Diligence - vīrya

- Equanimity - upekṣā

- Humility - hrī

- Heedfulness - apatrāpya

- Non craving - alobha

- Non violence - ahiṃsā

- Absence of hatred - adveṣa

- Mental dexterity - praśrabdhi

- Exertion - arpamada

Concomitant Mental Faculties - General Functions of Defilement

- Ignorance - moha

- Non diligence - pramāda

- Idleness - kausīdya

- Non belief - aśraddhya

- Torpor - styana

- Restlessness - *auddhatya

Concomitant Mental Faculties - General Functions of Evil

- Lack of self respect - āhrīkya

- Shamelessness - anapatrāpya

Concomitant Mental Faculties - Minor Functions of Defilement

- Anger - krodha

- Hypocrisy - mrakṣa

- Parsimony - mātsarya

- Envy - īrṣyā

- Affliction - pradāśa

- Violence - vihiṃsā

- Enmity - upanāha

- Deceit - māyā

- Fraudulence - chatya

- Arrogance - mada

Concomitant Mental Faculties - Indeterminate Functions

- Repentance - kaukṛtya

- Drowsiness - middha

- Reflection - vitarka

- Investigation - vicāra

- Passion - rāga

- Hatred - pratigha

- Pride - māna

- Doubt - vicikitsā

Neither Substantial Forms Nor Mental Functions

- Acquisition - prāpti

- Non acquisition - aprāpti

- Communionship - nikāyasabhagata

- Thoughtlessness - asaṃjñika

- Thoughtless ecstasy - asaṃjnika samāpatti

- Annihilation trance - nirodha samāpatti

- Life - jīvita

- Birth - jāti

- Stability - sthiti

- Decay - jarā

- Impermanence - anityatā

- Name - nāma kāya

- Sentence - pada kāya

- Phoneme - vyañjana kāya

Three Unconditioned Dharmas

- Space - ākāśa

- Extinction through intellectual power - pratisaṃkhya nirodha

- Extinction due to lack of a productive cause - apratisaṃkhya nirodha