Firecrackers have been banned or restricted in seven states this year — Delhi, Punjab, Haryana, Bihar, Maharashtra, West Bengal, and Tamil Nadu —the Supreme Court of India having deemed that bursting crackers is not an ‘essential practice’ to Hinduism, and cannot be offered the protection of religious freedom under the constitution. This debate about whether firecrackers are, in fact, a Hindu practice has raged on for years now. The multiple literary and historical references to fireworks will be covered briefly in this piece, in an attempt to establish the antiquity and significance of the practice for Hindus. However, this evidence must not be taken to mean that if the tradition of firecrackers was a more recent practice (a few centuries later than claimed), that it is not of equal religious sanction or significance.

Customs of Dīpāvalī

The whole season leading up to Dīpāvalī was, in the past, a season of joyous celebrations, culminating in a grand moonlight festival known as the Kaumudi-mahotsava. Dīpāvalī has the observances of many festivals incorporated into it — for instance, the custom of consuming a medicinal preparation of ginger and molasses is a remnant of Dhanvantari Jayanti, that occurs on the preceding day. The day prior to Dīpāvalī-caturdaśī is Dhana-trayodaśī, when women worship Lakṣmi and drive out Alakṣmi with winnowing baskets. Dīpāvalī then begins with a sacred oil bath at sunrise, wearing new clothes, partaking in a feast with family, and bursting crackers. The oil bath itself is said to cast off Alakṣmi, as Lakṣmi is said to reside in the oil.

Crackers are by no means a new tradition, but rather among the oldest, most essential features of Dīpāvalī. Firecrackers are not part of the merry-making and festivities, but an integral religious belief, due to the association of departed ancestors with the holy month of kārtika. Our pitṛ or manes come down during Mahālaya pakṣa and in order to find their way back to their world, we light up their path — lamps are set out on pillars and on top of houses and poles, crackers are made to burst mid-air. In Bengal, lamps are floated on water for this purpose. In the Skanda Purāṇa the term for this is ulka-dāna, where it is stated that “When the sun is in Libra, on the nights of Caturdaśī and new-moon day, men should celebrate the festival of “showing the path unto the pitṛs” with firebrands in their hands”. In a Saṃskṛta text called Dīpāvalī-kṛtya (on the things to be done on Dīpāvalī), it is prescribed that that after an oil bath in the early hours of the morning, Lakṣmi, Kubera and Indra are worshiped, and a ritual called Dīpa-śrāddhā — worship of ancestors with lamps — must be performed. The pitṛ are to be offered ulka-dāna, and mantras are to be recited to the lamps for lighting their path to the other world. One of the ślokas in the text reads: *Leaving the realm of Yama, they who came down during the Mahālaya, let they, the ancestors, depart making their way with the help of these brilliant illuminations.* The second day after Dīpāvalī is called Yama-dvitīya and water-libation offered to Yama is enjoined by the texts.

Literary and Historical Sources

The Kārtika Māhātmya urges one to light up the skies and pray for the fortune of being able to attain Viṣṇuloka. Sparklers, flaming torches and rockets (called bāṇa) have existed since the ancient times. Gustav Oppert, in his book On the Weapons, Army Organisation, and Political Maxims of The Ancient Hindus, With Special Reference to Gunpowder and Firearms states that the oldest mentions describing gunpowder and its applications — for both weapons and for entertainment — are found in the Śukranīti, the use of missiles and firearms being a well-known fact in ancient India. The preparation of different types of explosive powders such as gunpowder were kept secret, restricted to certain jātis. Oppert writes:

India is the land of fireworks; no festival is complete without them, and as the materials for their manufacture are all indigenous, and of easy access, there is no difficulty in gratifying such desires.

The raw material for gunpowder referred to here is saltpeter, which is widely available and known to have been used in the making of rockets and other fireworks in China and India. Saltpeter is known as sauvarcala and yavakṣāra in the Śukranīti and Rasārṇava. In the 7th century text Daśakumāracaritra by Daṇḍi, there is mention of yogavartikā (a magic wick) and yogacūrṇa (magic powder), of which saltpeter was probably the basis.

Primitive firework mixtures were known and used by the Hindus for many centuries, and took forms known as gola, paṭāka, vengaguedi, koroo, adirvedi etc. Hindu pyrotechnists also used a substance called “Chinese fire" burnt in paper, bamboo containers and earthenware pots, called tubri. Other fireworks used in India are abusavanani (rockets), anar, phuljari, burusu, chandrajota etc.

The Śukranīti, a text said to be from the 4th century B.C. of the Vaidika era (dated by modern historians to the 4th century) authored by Śukrācārya contains the recipe for firecrackers:

By varying the proportions of the ingredients, viz., charcoal, sulfur, saltpeter, realgar, orpiment, calx of lead, asafoetida, iron powder, camphor, lac, indigo and the resin of Shorea robusta, different kinds of fires are devised by the pyrotechnists giving forth flashes of starlight.

Explicit references to fireworks are scant prior to the 1400s, although there is plenty of circumstantial evidence for the same. Starting from the 15th century to the 18th, however, literary and historical references are plentiful. Abdur Razzaq, the ambassador from the Court of Sultan Shah Rukh, who stayed in Vijayanagar in 1443 during the reign of Devarāya II, mentions the use of pyrotechny in the Mahānavamī festival. *One cannot without entering into great detail mention all the various kinds of pyrotechny and squibs and various other amusements which were exhibited.* It can be inferred that various kinds of fireworks were used at Vijayanagara in 1443 A.D. and possibly many years earlier for purposes of entertainment at festivals. Ludovico di Varthema, a 15th century traveler also described the city of Vijayanagara:

But if at any time they (elephants) are bent on flight it is impossible to restrain them; for this race of people are great masters of the art of making fireworks and these animals have a great dread of fire, and through this means they sometimes take to flight.

This account confirms the use of fireworks in warfare to scare horses and elephants and cause casualties. Duarte Barbosa (also 15th century) in his travels wrote of the use of rockets at a Brahmin wedding in Gujarat: *During this time they [the bride and the bridegroom] are entertained by the people with dances and songs, firing of bombs and rockets in plenty, for their pleasure.* It is evident from this reference that fireworks were manufactured in India on a large scale by at least the 16th century, being so available in plenty in Gujarat for use during weddings and for other festivities.

Panguni Uttaram festival: The image of Gaṇeśa is taken in procession, preceded by a dancing girl performing at the accompaniment of musicians and fireworks. Wall painting at the Tyagaraja Temple, Tiruvarur, 17th century

Panguni Uttaram festival: The image of Gaṇeśa is taken in procession, preceded by a dancing girl performing at the accompaniment of musicians and fireworks. Wall painting at the Tyagaraja Temple, Tiruvarur, 17th century

As for Indian sources, a Sanskrit work called the Kautukacintāmaṇi by Gajapati Pratāparudradeva of Orissa (1497-1539 A.D.) mentions the manufacture of specific fireworks. The folio contains detailed chemical constituents and formulae for the preparation of different fireworks. The list of chemical ingredients for pyrotechnic mixtures including sulfur, saltpeter, charcoal, iron powder, etc. in the text speaks for itself, as they are the very basis of pyrotechny, and available in India from early times.

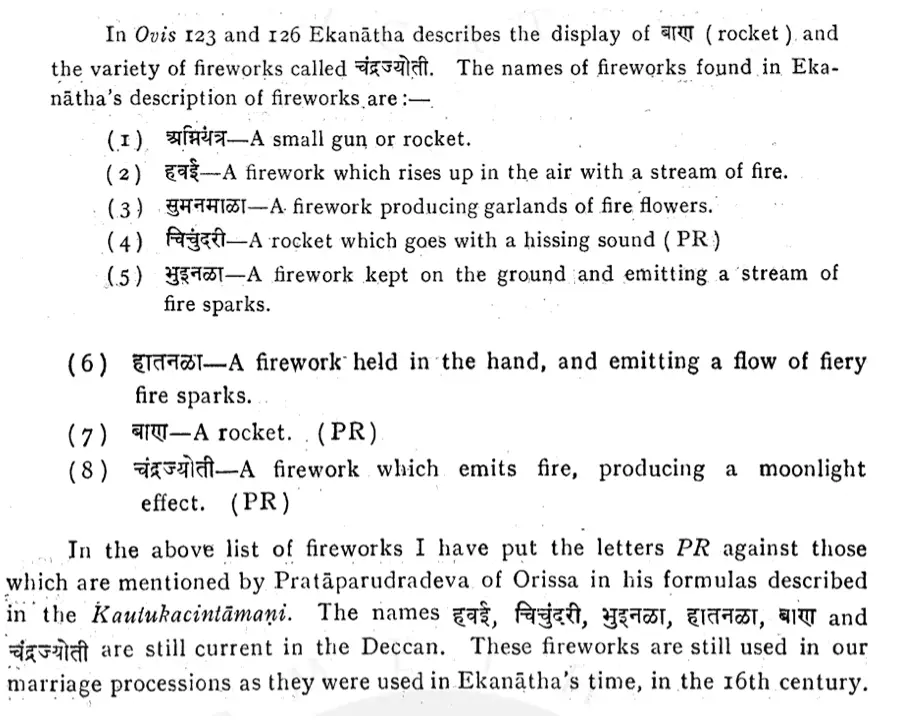

Another text called the Ākāśabhairava Kalpa (1500 A.D.) contains references to guns and fireworks — describing the pyrotechnic display of fireworks witnessed by the king on Dīpāvalī festival. It contains details of structures on which bāṇas or rockets were fired off of (bāṇavṛkṣān), and how the display appeared like a fly-whisk or a chowrie. Sant Ekanātha’s Marathi poem Rukmiṇī-Svayaṁvara (1570 A.D.) names and describes a multitude of fireworks (image 2).

From Gode, P. K. The History of Fireworks in India between A.D. 1400 and 1900. Transactions of the Indian Institute of Culture, vol. 17. Bangalore: Indian Institute of Culture, 1953. p. 16-17

From Gode, P. K. The History of Fireworks in India between A.D. 1400 and 1900. Transactions of the Indian Institute of Culture, vol. 17. Bangalore: Indian Institute of Culture, 1953. p. 16-17

Another Marathi poet, Sant Ramadāsa (1608-1682 A.D.) refers to guns and fireworks while describing a bhajana accompanied by the display of fireworks. He also describes a firework display before King Rāma at night. To conclude, it is amply evident that the practice of the use of fireworks for festivities was commonplace by 1600 A.D. in Gujarat, Maharashtra, Orissa, Vijayanagara etc. Clearly regarded as both a cultural and religious practice, it is imperative that we understand not only their religious significance but also the pre-eminent position of fireworks in Hindu processions, celebrations and festivities. This article is a plea asking that Hindus rediscover joy in their festivals, and do not allow stifling media narratives, NGO guilt-tripping and governmental suppression to succeed in dampening this year’s Dīpāvalī festivities. Śubha Dīpāvalī.

References

- A History Of Hindu Chemistry Vol. I by Praphulla Chandra Ray

- Festivals, Sports and Pastimes Of India, V Raghavan 1979

- Gustav Oppert, ‘On the Weapons, Army Organisation, and Political Maxims of The Ancient Hindus, With Special Reference to Gunpowder and Firearms’

- Gode, P. K. The History of Fireworks in India between A.D. 1400 and 1900

- Transactions of the Indian Institute of Culture, vol. 17. Bangalore: Indian Institute of Culture, 1953