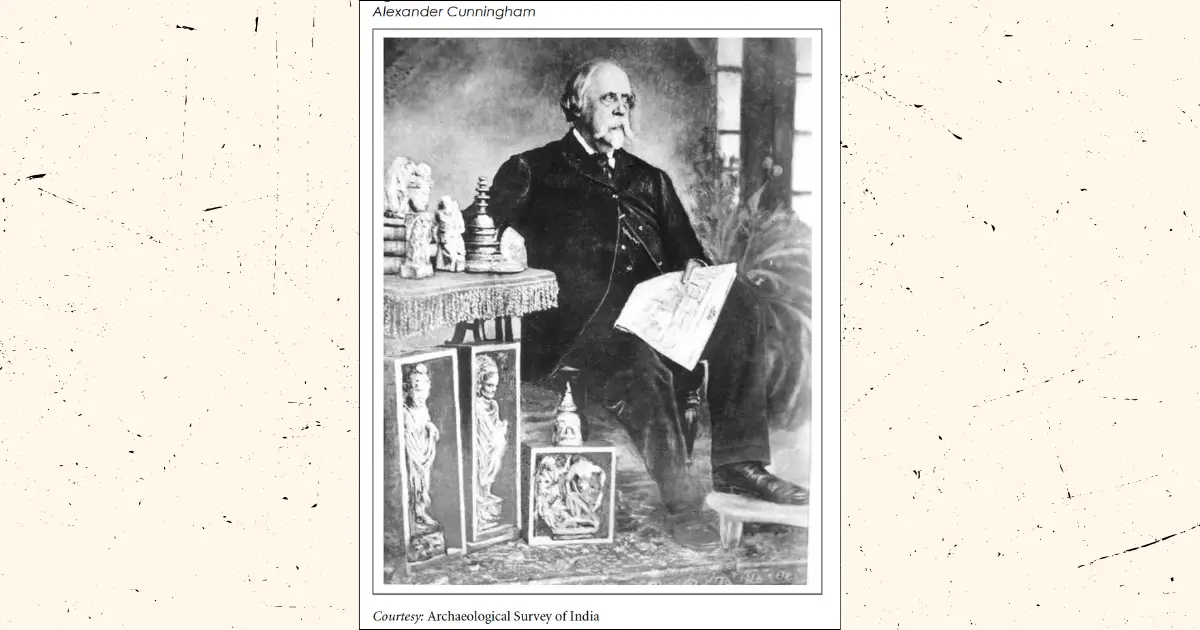

The history of the Archaeological Survey of India (ASI) is that of the regulation and institutionalization of the discipline of archaeology by the imperial government. This article delves into the reasons for the emergence of institutions such as the ASI, and aspects of the early history of the ASI such as its institution, paying special attention to the role of Alexander Cunningham, a man glorified today as the ‘Father of Archaeology in India’, but was little more than a plunderer and despoiler of priceless archeological sites in India. An understanding of the structure, origins and operation of the ASI offers critical insight into not only the contemporary issues within the institution, but can also aid in policy-making and institutional reform relating to India’s heritage and culture.

Colonial Context for the Emergence of Institutions

In India, the late 18th to early 19th century was a time of reorganization of the East India Company, when Company officials began to see themselves as bureaucrats furthering British imperialist motivations. Contemporaneously, the nature of knowledge production itself was also undergoing evolution, with the British attempting to consolidate political power through the production of knowledge.

The establishment and maintenance of England's colonies was contingent upon the processes of ascertaining, codifying, controlling, and representing historical narratives. The commission, compilation, storage, and publication of data on every possible subject necessitated significant exegetical and hermeneutical expertise and use of resources to generate and interpret. Following that, their capacity to document, organize, and interpret these vast amounts of information was critical to England's effective governance. In other words, Britain attempted to comprehend and govern India using their own forms of knowing and thinking. Indian society was reconstituted as a collection of facts, which were then assumed to be self-evident, and the belief was that administrative power stemmed from the efficient use of these facts.

A great many measures were undertaken to improve the colonial understanding of the various aspects of the social, religious and political landscape, including the documentation of culture and traditions, albeit flawed. The imperative to gather data was an element of the larger colonial project, which particularly shaped the investigative modalities devised by the British to generate knowledge. According to Cohn:

(a)n investigative modality includes the definition of a body of information that is needed, the procedures by which appropriate knowledge is gathered, its ordering and classification, and then how it is transformed into usable forms such as published reports, statistical returns, histories, gazetteers, legal codes, and encyclopedias.

This coincided broadly with creation of disciplines such as archaeology, museology, sociology, ethnology and ethnography, anthropology, etc. and sciences such as economics, ethnology, tropical medicine, comparative law, cartography, etc. as new areas of study that facilitated further representation, reference, and organization of the society being governed. This was the birth of institutions that were highly defined and related to administrative pursuits or fields of expertise. The singular purpose was the weaponization of information as a channel of imperial control. In the words of Dirks, “(t)he very Orientalist imagination that led to brilliant antiquarian collections, archaeological finds, and photographic forays were in fact forms of constructing an India that could be better packaged, subsumed, and ruled.”1 Given India’s paucity of written historical records, material remains of past and specimens of flora, fauna and geology were of crucial importance in the reconstruction of the past by the colonizer with the intention to aggrandize his rule.

Surveying India

The word ‘survey’ evokes a multitude of meanings: to examine; to measure land for the purpose of establishing boundaries; to inspect; and to supervise or keep a watch over persons or places; to establish the monetary value of goods or objects. For the British in India surveying meant the exploration of the natural and social landscape, from the mapping of India to collecting botanical specimens, to recording architectural and archaeological sites. Therefore, the concept of the survey came to cover any systematic and/or official investigation into and the documentation of the natural and social features of the Indian empire2.

In the early 1800s, the identification and mapping of several archaeological sites was incidental to the carrying out of revenue surveys. The first Surveyor General of India, Colin Mackenzie carried out non-archaeological surveys which also recorded monuments and sites. He visited “nearly every place of interest south of the Krishna river, and prepared over 2,000 measured drawings of antiquities, carefully drawn to scale, besides facsimiles of 100 inscriptions, with copies of 8,000 others in 77 volumes”.3 From the 1830s onwards, archaeological research received significant impetus, spurred by the deciphering of the brahmi and kharosthi scripts which made archaeological discoveries appreciable and more significant.

The Beginnings of the ASI

The need for the government to undertake a methodical survey of archaeological sites was expressed by Alexander Cunningham (1848) who successfully lobbied Lord Canning in 1859 to establish the Archaeological Survey of India. Formerly an army engineer, Cunningham became the first director of the ASI. He showed a great enthusiasm for Buddhist relics, and proposed that the survey be geographically guided by the accounts of the two Chinese Buddhist pilgrims, Faxian in the 5th c. AD and Xuanzang in the 7th century AD. He believed that a search for Buddhist ruins would demonstrate that Brahmanism was not the paramount religion in India and this knowledge would facilitate the propagation of Christianity. Therefore, the systematic archaeological exploration of India was first advocated in order to make the acceptance of Christianity easier, and aid the political advancement of the British.

Cunningham headed the Archaeological Survey for two terms, from 1861-5 and 1871-85. Over the course of nineteen years he covered a surprisingly large territory, including the entire Gangetic valley, Panjab and the Northwest Frontier Province, central India and Rajputana. The results of surveys done by him or by his assistants were published from 1862-87, in 23 volumes of Reports. Along with his basic field reports they also feature his analytical writings on historical geography, numismatics, inscriptions, architecture and sculpture.

Although the body of work is impressive, for Cunningham, excavations were never a planned and meticulous effort with a definitive aim, but rather, simply a matter of haphazard probing. They were not thorough explorations but hurried visits from site to site, scarcely doing justice to them. As Abu Imam writes, “Very often his explorations would degenerate into mere object hunting expeditions: he would visit the site, clear the jungle around, and employ a gang of laborers to search for coins, inscriptions and sculptures, often offering rewards ‘for even a single letter'. Then he would himself scour the countryside, gardens, bushes and the homes of the people. He collected a large number of inscriptions and sculptures by this means, particularly in Bhārhut, Kauśāmbī and Mathurā.”4

The ASI was responsible for not only recording but also the preservation of historical sites. However, very often, the fate of artifacts and antiquities and the question of preservation of what was recorded was of little concern to the authorities. Restoration and preservation of sites was not part of the scope of the first survey: Lord Canning had specifically stated that to restore ancient monuments, or even arrest their further deterioration would require an expenditure far beyond what the government was prepared to accept.

Shockingly, Cunningham's terms of employment stipulated that he be allowed to take for himself a substantial portion of artifacts that were unearthed during the course of excavations and surveys. He accumulated a massive collection of art and artifacts for himself, and, on the disbanding of the first survey in 1865, he returned to England for five years, and carried out a profitable business in coin selling, particularly to the British Museum. He had also “amassed a unique and unrivaled collection of coins, seals, stone implements and other objects including smaller statues and relic caskets.”5

Alan Trevithick describes how idols, fragments, manuscripts, coins and other artifacts continued to be carried off by British excavators and other European gentlemen as they wished, and by others, even after the establishment of the Archaeological Survey. It was as if the practice of loot was designed into the survey. “The haphazard looting of the past had achieved some degree of organization, no doubt, but the destruction of the archaeological value of sites, as we currently recognize such value, continued apace”.6

Conclusion

The contemporary relevance of this exploration into the past of the ASI is crucial for multiple reasons. First, an understanding of the epistemology (method and theory of the production of knowledge) of archeology as established by the ASI serves as an exemplar for the politicization of knowledge itself to entrench the British stronghold in India. The discussion also speaks to the manner and purpose for which other colonial fields of study operate. Second, delving into the structure and functioning of the ASI, considering it as a model for contemporary India’s cultural institutions can generate deep insights for policy-making and bureaucratic reform for the modern nation state. Arguably, one the reasons that archaeology in modern India is sub-par and inadequate and is not on par with Western scholarship is that it does not demand rigor in scientific planning and analysis. Moreover, restoration and preservation are more often than not, shoddily and carelessly executed, despite being an age where state-of-the-art preservation techniques are available. Bureaucratic reform of the ASI and the upgradation of its resources and output must involve breaking away from its origins as a system of loot in disguise as a second-rate colonial institution.

References and Footnotes

- Chakrabarti, Dilip K. The Development of Archaeology in the Indian Subcontinent. World Archaeology 13, no. 3 (1982): 326–44.

- Cohn, Bernard S. Colonialism and Its Forms of Knowledge: The British in India. Princeton University Press, 1996.

- Guha-Thakurta, Tapati. Monuments, Objects, Histories: Institutions of Art in Colonial and Post-Colonial India (Cultures of History). United Kingdom: Columbia University Press, 2004.

- Imam, Abu. 1966. Sir Alexander Cunningham and the Beginnings of Indian Archaeology. Dacca: Asiatic Society of Pakistan

- Trevithick, A. (1999). British Archaeologists, Hindu Abbots, and Burmese Buddhists: The Mahabodhi Temple at Bodh Gaya, 1811-1877. Modern Asian Studies, 33(3), 635–656.

- Dirks, Nicholas B., and Bernard S. Cohn. “FOREWORD.” In Colonialism and Its Forms of Knowledge: The British in India, x. Princeton University Press, 1996.

- Cohn, Bernard S. “INTRODUCTION.” In Colonialism and Its Forms of Knowledge: The British in India, p. 7. Princeton University Press, 1996.

- Imam, Abu. 1966. Sir Alexander Cunningham and the Beginnings of Indian Archaeology. Dacca: Asiatic Society of Pakistan. p. 17

- Imam, Abu. “Sir Alexander Cunningham (1814-1893): The First Phase of Indian Archaeology.” Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland, no. 3/4 (1963): 200.

- Sir Alexander Cunningham and the Beginning of Indian Archaeology. by Abu Imam. Asiatic Society of Pakistan Publication Number 19. Dacca: the Society. 1966. pp. 232, cited in Trevithick, Alan. “British Archaeologists, Hindu Abbots, and Burmese Buddhists: The Mahabodhi Temple at Bodh Gaya, 1811-1877.” Modern Asian Studies 33, no. 3 (1999): 647.

- Trevithick, Alan. “British Archaeologists, Hindu Abbots, and Burmese Buddhists: The Mahabodhi Temple at Bodh Gaya, 1811-1877.” Modern Asian Studies 33, no. 3 (1999): 647.