Many younger Hindu intellectuals, faced with the convert-or-die choice that Western modernity has brought to our doorsteps, have come to the conclusion that the idea of defining ourselves through limits is, well… limiting. No doubt, putting limits on oneself when your rivals do not, is a recipe for defeat; but to be unable to see that the ideal of an existence without limits is a recipe for all kinds of immorality, is equally problematic.

The idea of limits is a fundamental idea in all societies, both Traditional and Abrahamic. The limits themselves may be different for different cultures, but all self-definition is engineered through the embrace of limits and the drawing of red-lines. Yama and Niyama. How much to eat? What to eat? What not to eat? How much to drink? What to drink? What not to drink? How much pleasure is to be pursued? How many spouses to have? How many children? How many clothes, vehicles, houses? How many genders? How many Gods? How much to talk? How to talk? How much to keep? How much to share? With whom to share? When accepted limits around these (and many other) questions are breached, societal judgement falls upon us.

The idea that life can be lived without limits is a peculiar and very recent innovation in human thought, and it has been made possible by the availability of enormous surplus to some of us. Children, from a young age, are no longer taught to curb their desires, but to indulge them… to ‘dream’. And when some of those dreams do come true, that approach stands vindicated.

The vision is that we will invent/discover our way out of the need to follow those pesky limits - new energy sources will be tapped, new efficient technologies created, and new sources of mineral wealth will be opened up, either here or on Mars. Hell, the last three hundred years are proof that this way of thinking about the world is legitimate, even in the eyes of the Gods. Look, how they’ve rewarded us for our audacity! If the techno-optimists do indeed figure this stuff out, then Manifest Destiny is indeed their birthright; and the traditionalists with their limits and lines were wrong all along - dinosaurs from an age when those limiting ideas were useful to maintain quaint anachronisms like community and identity.

BUT, what if those problems are never solved? What if we are living off the future, subsidized by the world and resources that our children were destined to inherit? And I mean that not just from a resource and pollution point of view, but also from a culture and well-being point of view.

We’re blowing the accumulated cultural and knowledge capital of a thousand generations of ancestors in a mere hundred years, all in order to underwrite a bet placed in the future.

When individuals do that and succeed, they are heroes, and when they fail, they are fools.

At the very least, we must enquire into the alternate point of view.

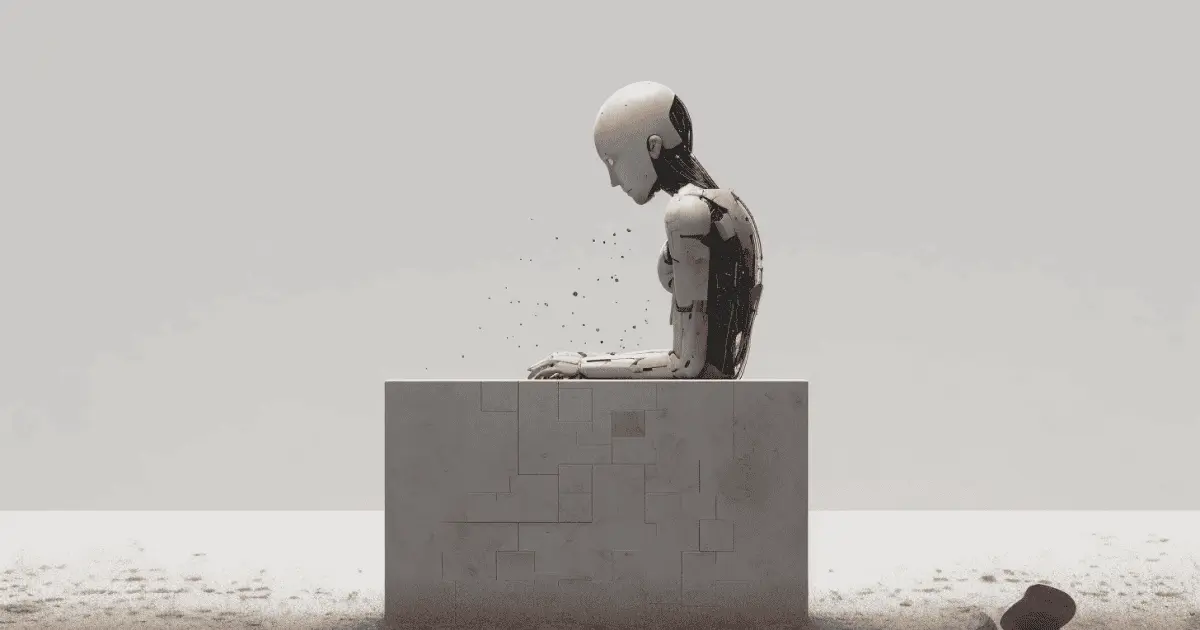

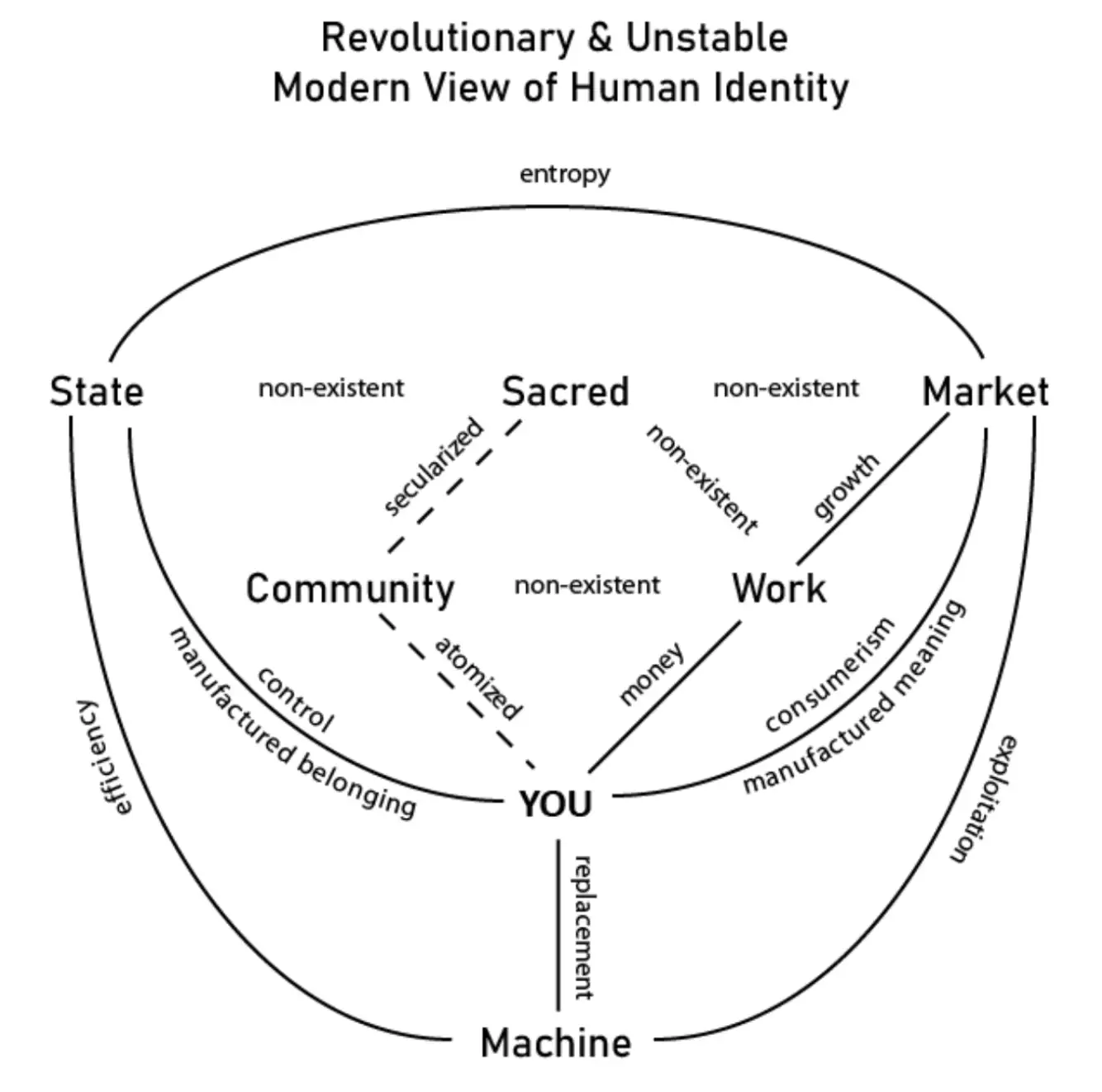

The ideal of Limitless-ness, like its sister ideals of Liberty and Equality, can only be pursued when subsidized by extreme surplus, which itself can only be produced by extreme mechanization of all aspects of human society. In such a society, any “inefficient” process must be replaced with a more efficient process. This is the only way that limitless-ness can be approached in the material world. So, the sequence is clear - initially machines help get a job done, then as their sophistication grows, they start to do the work of people, until eventually, they replace people altogether. The complex, high-efficiency world that this level of mechanization creates still finds a place for people, but the nature of work that a vast majority of people get to do has changed in four significant ways.

- It is no longer communal.

- It is no longer sacred.

- It is no longer connected to identity, and

- The person no longer has a sense of ownership over the work.

These losses are huge losses, the psychological effects of which we no longer comprehend because we simply don’t know any better.

So, we’re seeing two major shifts – one, traditional human work starts to be done by machines; and two, people are herded more and more into working ‘arid jobs’. Now, because of the higher efficiency of the system as a whole, surplus is generated which gets distributed among some people as higher and higher salaries. This may appear to be a win (to some), but by the standards of the old world (community, sacredness, identity, and ownership), it is clear that we are all spiritually impoverished when we accept this Faustian bargain - not to mention that very many of us do not even see the economic benefits of this move. It may be possible to reach a sweet spot with regard to mechanization of society – a compromise between the ease of the new model and the soul of the old model. This is what I call the ‘small is beautiful dream’. For this to happen organically, people who have lived their entire lives within a mechanized world have to be re-introduced to the old-world ideal of work not merely as an activity to earn money, but as a self-definitional activity that simultaneously connects one to both community and the sacred.

The Accusation of Drudgery

The Public Relations arms of the mechanized world paint low-tech work as “drudgery”, but anyone who has worked in a paddy-line singing harvest songs with her comrades, or on the roof of a house stitching thatch with his neighbours, knows that it is far from true. In any case, I am not calling for the establishment of a nation-wide Gandhigram. What I am calling for is a conscious appraisal of machines and their place in our lives.

Beauty and Perfection

Ontologically speaking, the greatest loss that we face with greater mechanization, is the loss of ownership over Beauty and the Pursuit of Perfection. Both these activities are now firmly in the grasp of the Machine. With the coming AI revolution, even the formerly lionized artists, designers and musicians will find their world devastated. We have relinquished control over the very well-springs of daily spirituality. In the old-world, our pursuit of perfection was in fact a prayer, and the result of that pursuit was a product of beauty that was literally an offering to the Gods, a naivedyam.

Prosperity

True that the old world had less surplus. Nevertheless, the real human question is not how much surplus, but what does that surplus get us in terms of well-being? To get a sense of what that question means, we can ask a few questions – “Why is it that we can no longer afford to keep cows?”, “Why is it that bulls have to be killed?”, “Why is it that we can’t afford to maintain a thatched roof?”, “Why is it no longer possible for us to build traditional temples without busting the bank?”, “Why can’t we afford to maintain our water bodies (kuḷams or kalyaṇis)?”, “Why are the costs of performing a yajña today astronomical?”

This is not entirely a question of priorities. Even people with the right priorities find that doing any of these things is prohibitively expensive. So then how come our “dirt-poor”, subsistence farming ancestors were able to do all of these things without batting an eyelid? How did they bring up six, seven, eight children when we struggle to put one through school? No doubt, our expectations around life have changed, but there is a kind of prosperity here that we have entirely lost track of today - a quiet prosperity. And it wasn’t all at the micro scale. Even the macro could manifest this sensibility. Between the 11th and 12th centuries CE, the Choḻa rulers and their subjects built upwards of fifty grand temples in a 50 km radius around just one town, Kumbakonam. If the modern Indian state was to embark upon such a project over a similar timeline, it would go bankrupt. Even attempting to maintain these temples in pristine condition today would be a recipe for bankruptcy. So, who is richer – the Choḻa Empire or the Modern Indian State? Europeans acknowledge this reality too. The Notre Dame could not be built today. Neither the skills nor the wealth exist.

Treadmill

What we are unwilling to acknowledge is that what goes by the name of development today is not a destination, but the first step in the embrace of an extremely expensive annual maintenance contract - and that too, a contract that we pay in perpetuity. Add to that the requirement of the ‘growth-based economy’, and we have a recipe for disaster. It is not only a treadmill by definition, but a treadmill that is supposed to go faster and faster every year, to maintain what is known as ‘growth’. How such a thing would even be possible without the greater and greater utilization of limited resources or outright robbery in the short term, remains a mystery. War, therefore, becomes the inevitable end-game in this model of development. America, for example, has entered into twelve overt wars and nine covert wars in the mere seventy-five years since WW2. That’s how it maintains its resource flow. The roads and services that the American taxpayers think they pay for, are also funded by the blood-stained oil and lithium from these twenty-one wars.

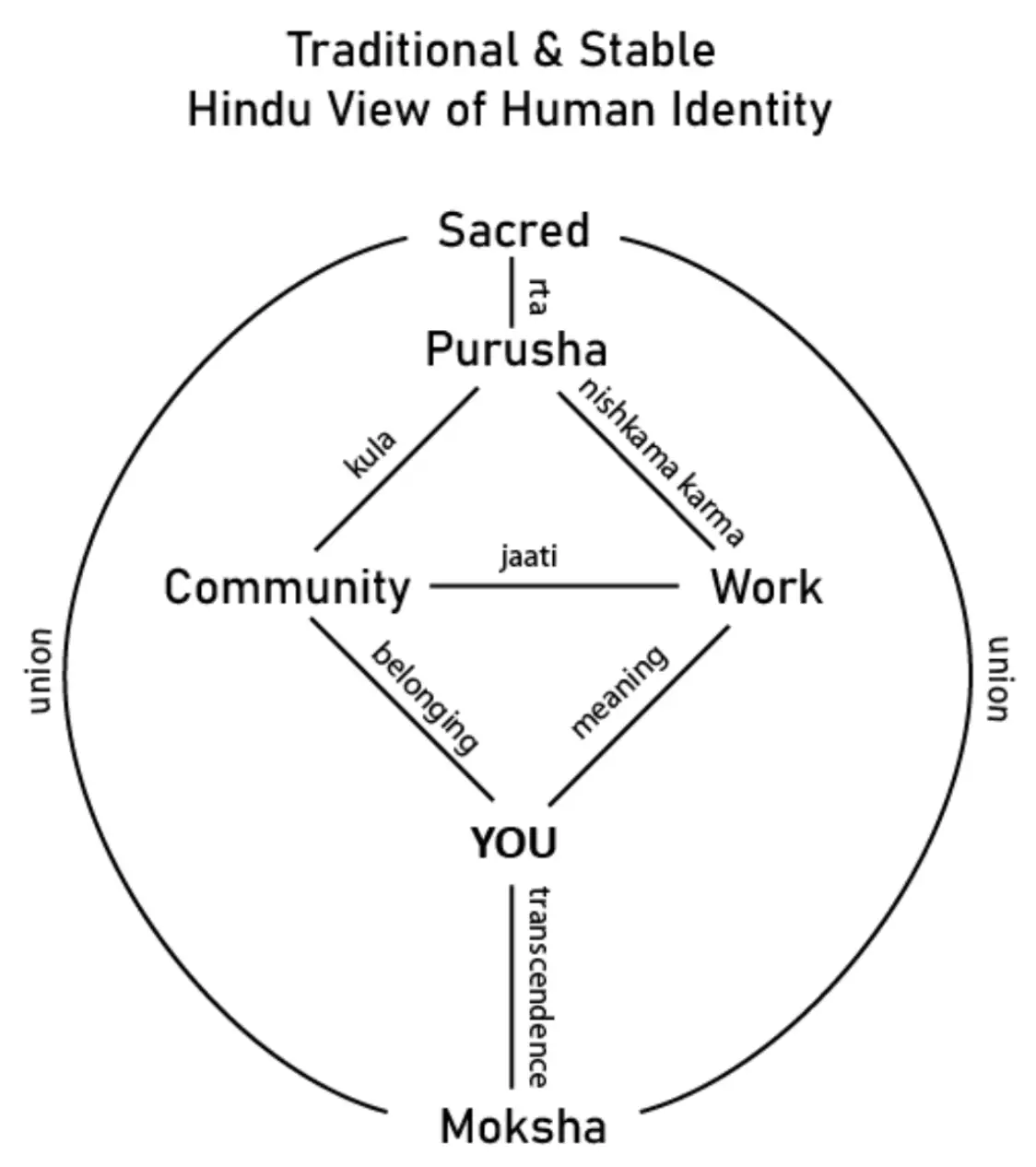

Security to Insecurity

What the Old Way provided, at least in Bhārata, was direct access to the sacred, to identity, belonging, and puruṣārtha. Every individual was guaranteed family, community, tradition, daily work, and if they were willing, a spiritual path. The fundamental psychological fruit of this system was to bestow upon the individual, an inviolate sense of stability, and therefore security. One can still see this in people from remote villages, their utter lack of anxiety. The modern person, on the other hand, is marked out by anxiety, a high frequency nervousness, a whirring neurosis, a need to perform, and the charade of presenting a mask to manipulate emotional outcomes in inter-relationships. You can tell a city guy from a villager simply from the way they stand or sit. You can tell an American from an Indian simply from the self-consciousness inherent in the way they talk. You can tell your grandma from your mother simply from the look in her eyes. The neurotic vibration induced in us by modern living is a thing of everyday experience for most of us. We just choose to ignore it. The autistic spectrum today claims one in every twenty American children. We can’t be far behind. Civilizational insecurity resonates.

Claustrophobia

The fall of the Old Way and its replacement with a foreign system brought material riches, but also psychological hell. The foreign system that’s now imbibed into our operating systems hinges on individuals having to constantly prove supremacy over colleagues, on a treadmill owned by someone else, who also happens to believe that said individuals are dispensable. Not only are all the old identities considered passe; but all the new identities are ephemeral and explicitly profane. The psychological cost of this is still being measured in KPIs of stressful lives, broken families, suicide, depression, inverted population pyramids, drug abuse, autism and lost childhoods.

Regardless, this model is today so ingrained in the minds and lives of modern people that we can’t imagine that any other way could possibly fulfil our needs. Add to this, the constant barrage of propaganda that the media arms of modernity spew out; in order to keep us all convinced that this journey is essential, the destination is vital, and all other ways are too painful to contemplate. Imagine a world without internet, they say. Well, some of us don’t have to imagine such a world, it was reality a mere heartbeat ago, and life then was perfectly fine. Anyway, that’s just to illustrate how fear is bred into us. The “past” has been cast as a cage, and any thought of it designed to evoke claustrophobia.

The irony of course is that no person who actually lives in the “past” feels claustrophobic, it’s the people who live in the future (in their heads), who do.

Escape from Claustrophobia, the Western Way

The Western way of dealing with this largely self-imposed insecurity and claustrophobia is to project all human emotions into the future. The future becomes a sanctuary, a place of escape, where the limitations of the “past” can be overcome, where the tight feeling in our chests will find release. The “future” comes to be imbued with religious overtones. The idea of “Progress” is deeply connected to this imagination of the future.

“Progress Theology” is a virtual credo now among all the peoples of the world. The almost feverish need to be involved in anything “Progressive” is now a global phenomenon, only resisted by the most recalcitrant of cults. The fear of being “left behind” is a visceral entity that exists in the pits of all our stomachs.

The “Future” and its inevitable Marriage with the idea of Material Sophistication

Inevitably then, this imagination of the “future” as “progress” comes to be inextricably linked with an ever-upwards sloping trajectory of material sophistication. After all, what else could possibly be a visibly manifest representation of our progress? It has to be something physical. Something more complex than what existed before. Something that visibly and experientially manifests a quantitative improvement from what existed yesterday – faster, stronger, bigger, more efficient… simply more.

The Hindu View

The Hindu view, on the other hand, does not anchor on time or on material sophistication, but on Dharma. Any era that is more dhārmika is aspirational. Any era that is less dhārmika is less aspirational. Whether that era lies in the past or the future is irrelevant. Whether that era has more machines or less is irrelevant.

Anybody who buys into the idea that the present is always better than the past, must per force also buy into the idea that the future will always be better than the present. This is Progress-Theology and it’s a very pernicious religion. It excuses every depravity of history as a mere aberration that must be ignored because it was a step on the ladder to the “future”. For a true Hindu, what is better or worse can never be determined by the impartial flow time, nor by its proxy – increasing material sophistication, but by the widespread establishment of Dharma. If Dharma was more widely established in the 9th century, than today, then certainly the 9th century is more aspirational than today. The same logic would apply for say, 3000 BCE or 2400 CE.

Mortality and Novelty

The reason for this deep psychological need to hang our hopes on something other than what we currently have, seems to have something to do with our sense of personal mortality. The fact that we start dying from the moment we are born seems to be embedded deep in our kośas. Sure, we look back at the past as a time when we were younger and more vital; but the paradoxical corollary of this is that we also look to the future as a domain where we can be young again, where we can resist the passage of time by doing something new and re-inventing ourselves, thereby manifesting a psychological rebirth. Of course, it’s not real and it’s ephemeral, but that’s the reason why we have to go looking for this feeling again and again. The very ephemerality of every invention is the engine that drives the next cycle of re-invention. Boom and Bust. It’s the same reason why individuals pursue new lovers, new travel destinations, new clothes, new restaurants, new jobs etc. It’s the same reason that Western civilization pursues “Progress”. Every re-invention, or new location, or relationship is a piece of space-time that is temporarily carved out of the inexorable march of our mortality towards its pessimistic end, where we can pretend that we are young again. That’s why the Novelty-Treadmill is so important in the Western self-imagination (that we have all now bought into). The Novelty-Treadmill is the modern stand-in for immortality, a crutch of the utmost psychological importance. It can’t be let go of, lest we are “left behind”.

Magic and Tragic

For example, let’s take an institution or even a place, like a house. If it is associated with new-ness or growth and youth, we feel alive when we are part of it – it is Magic. When the exact same place is associated with old-ness, stasis, and age, we feel depressed when we are part of it – it becomes Tragic. Like, I would never go back to my college again, it is just too anachronistic an experience to subject myself to - the buildings are decayed, the people that made up that place in my imagination are all gone, and I no longer find aspirational the ideals that it represented. In other words, it feels like death. And I do understand that this is how most people feel about the “past”.

Some part of it is connected to the wrestling match that each of us is involved in with our mortality, but another part of it is how our minds have been conditioned: from once holding an essentially Hindu darśana (to the problem of mortality) to what is essentially now a Western perspective – Progress Theology.

Renewal of Eternity as Rebirth

So, how did traditional Hindus tackle this problem of mortality? For one, they did not believe that the creation of temporary distractions to help us ignore the problem, was a viable solution. The problem was much too serious for this kind of ad-hoc and shallow response.

All traditional communities looked at time quite differently from Abrahamics (and Modernists). The passage of time is seen as a play of divinity. Our role here is to align ourselves with archetypes. Our sense of immortality comes then, not from generating novelty, but from the Renewal of Eternity that happens when we play our parts. Just as our communities are fractal fragments of the whole, so too are the fractal fragments of Time the reflections of divine time. Every moment is not one in a line of moments stretching unto the horizon of some dystopian Einsteinian shore, but a flash of divine possibility, representing all of Time in the Here and Now. We, Hindus, are alive now, not in the hereafter. We are connected to the Now because the Now is a fragment of Eternity, not merely a step on the way there. This is the reason why our heroic ancestors were never fixated on death - they had already tasted Eternity in the Now.

Consciousness Theory and Eternity in the Here and Now

This brings us to the doorstep of Consciousness Theory which sees every moment as brand-new, born from the fire of eternity, and pregnant with life. The more conscious we are, the more we are able to exist in the Here and Now in full awareness. Of course, wise Hindu men and women in every era have embodied this phenomenon in the traditional way; including more recently, a sage like Śrī Ramana Maharshi. Modern sages like Śrī Aurobindo, too, shone light on this phenomenon, generating an entire metaphysics around it. His optimistic vision posits consciousness as the light that will defeat time and therefore, death. When we are fully aware, we are alive in the Here and Now, and we drink straight from the fount of Eternity. Every passing moment carries within it the possibility of rebirth and therefore, of eternal youth. All that we need, to unlock this mystery, is the key of consciousness. The more awareness one is capable of bringing to bear on a moment, whatever is that moment’s nature, the more immortality that moment carries. Hindus have been granted four access codes as keys to the Now; jñana, dhyāna, niṣkāma karma, and bhakti. Now-Consciousness is the panacea for the claustrophobia induced by mortality and time-consciousness.

Of course, all of us have to live in the world at large. We have to remember the past and plan for the future, but we can see life as a series of Nows. The more we are able to do this, the more we free ourselves from the anxiety of the Future-Mind and its child, the Novelty-Treadmill. This was done at the community level, in Bhārata, through the traditions. The traditions are mechanisms for communities to renew Eternity year after year, thereby tying themselves to the grand movements of nature and stepping outside of their own fleeting egoistic emotions. The Western model, on the other hand, takes those fleeting egoic emotions very seriously, and puts the entire weight of a centralized structure behind physically manifesting those emotions. Unfortunately, the emotions are never satisfied, and more and more has to be generated every year on that imaginary ladder to self-fulfilment. So much so, that contentment has come to be seen as a cop-out, and the restless pain of modern living painted over with a brush of romanticism.

Take the recurring celebration of festivals or even daily cooking for instance. These are activities that have been performed since the dawn of cultural time, but we never tire of them (until recently in some circles). Why? Because they are acts of consciousness harnessed towards honouring the love we have for our families and the Gods. So, it is possible that the same activity can escape the shroud of Time when the conditions are right (that is, in the presence of Consciousness and Connection). And it is those conditions that Hindu metaphysics seeks to create within Hindu society, so that all Hindus and Hindu communities may forever have the keys to Forever.

Note

Saṃskṛta words in this article follow IAST standard diacritics, the Tamiḷ words follow ISO 15919 standard diacritics.