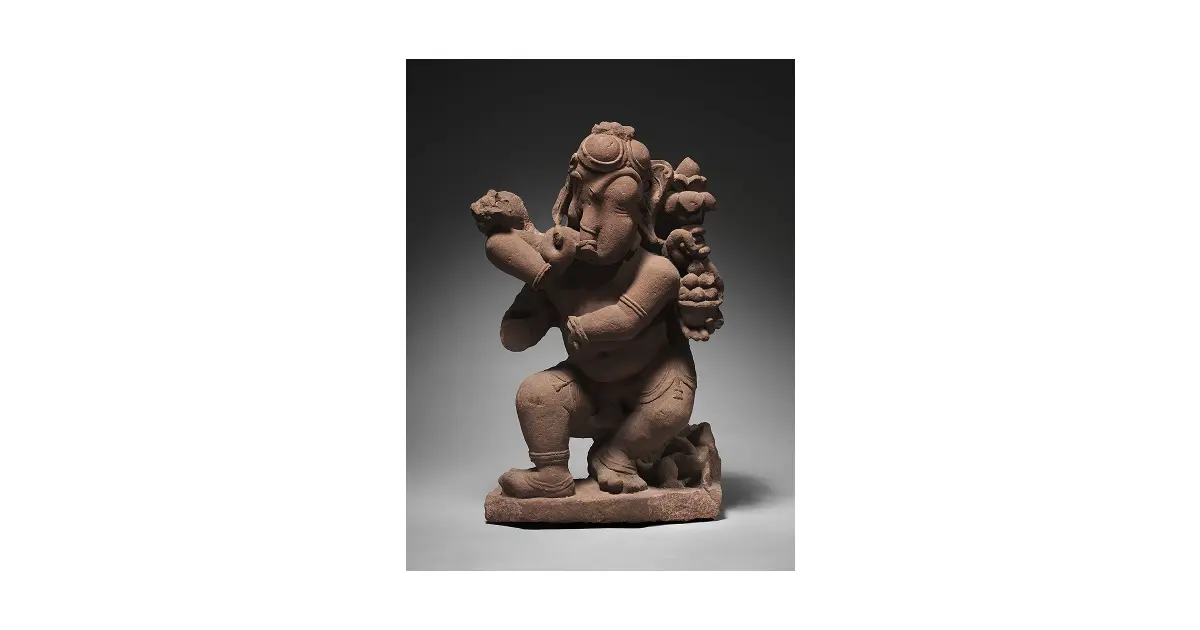

Gaṇeśa is one of the most recognizable figures of the Hindu pantheon, yet presents a striking paradox. He is both subordinate and indispensable: a pārśvadevatā, a minor or ancillary deity in ontology, yet ritually unavoidable at the threshold of every undertaking. He is vighneśvara, the Lord of obstacles, being both a vighnakartā, 'creator of obstacles' and vighnahartā, 'remover of obstacles'. His name is invoked before essentially every ceremony: before the recitation of mantras, before the start of journeys, before domestic rites of passage, and before royal or communal ceremonies. He is worshipped across sectarian divides—by Śaivas, Vaiṣṇavas, Śāktas, Buddhists, and Jains—making him not only the most popular but also the most ecumenical of the Hindu gods.

Emergence of Gaṇapati

The earliest text that foreshadows the emergence of Gaṇeśa is the Atharvaveda. Here, misfortunes, illnesses, and obstacles are caused by malevolent entities: grahas, piśācas, rakṣasas, and bhūtas. The Mānava-gṛhyasūtra (7th–5th centuries BCE) names four Vināyakas—Kūṣmāṇḍarājaputra, Śālakaṭaṅkaṭa, Usmita, and Devayajana—who obstruct prosperity, prevent childbirth, and cause mental affliction. They were propitiated with offerings of meat, wine, and other substances. By the first century CE, however, these Vināyakas had been consolidated into a single figure. In the Yājñavalkyasmṛti, the four Vināyakas become a single source of evil, of obstacles. Vināyaka also acquires the capacity to render ineffective the performance of religious rites. He acquires a new designation of gaṇādhipati, later also called gaṇapati or mahāgaṇapati, the lord or leader of gaṇas (gaṇa meaning a multitude, or hosts). Vināyaka also becomes known as the son of Ambikā (Pārvatī), appointed to his position by Brahmā, Viṣṇu, and Rudra. In the Bhāgavatapurāṇa (6th century), Vināyaka is described as vighnarāja (lord of obstacles), gaṇādhipa (lord of gaṇas). His evil nature is established by their association with rākṣasas, piśacas, bhūtas, and pretas.