This piece is Part 3 in a three-part short story series. Read Part 1 here, and Part 2 here.

The boys were whistling Ding Dong O Baby Sing A Song and there was no respite. It was Hero-worship all day long. For weeks, during intervals and during short breaks, they stuck to this tune. So when Shodashi first heard Colonel Bogey’s March it was not only a break from the monotony but also refreshing in its own right. It was more military in a way. And the nationalist in her could easily latch on to the inherent patriotism of this tune. She shook her head exasperatedly at her class boys - young, immature, caught up in their small universe, totally unaware of the world beyond their Air Force Station camp in Sulur, Tamil Nadu. At twelve the whole planet beckoned Shodashi and she was sure that one day she would be marching to this tune over the Bridge on the River Kwai. It would take her all of forty years to realize this dream.

Her father had bought them an LP of old English musical hits and apart from Pink Panther’s theme and Raindrops Keep Fallin’ On My Head, this was her favourite. So when the Officer’s Mess was showing the film ‘Bridge on the River Kwai’, she chose it over Mundhanai Mudichu, a hit Tamizh film of that year which was playing in the theatres. A cinephile from an early age, Shodashi preferred local cinema to Hollywood but this was an exception. She had liked the music and now wanted to watch what went with it. In her own imagination she had choreographed a whole routine to this tune and wanted to match the movie’s steps with her mind’s.

The core issue of this World War 2 movie was not very clear to her, the visuals showed a lot of army men in camps, ...they are POWs... said her father, she nodded knowingly not daring to ask a question. Was it pows or P.O.Ws? If the latter, what was the full form? At twelve Shodashi wanted to know the world, everything and anything in it. If you sing a tune in unison and march in step you can break a bridge, that is physics for you, her father added importantly, as though he had invented this law himself. See, see how they break their march to prevent a disaster...

This tune had haunted her all through her childhood and into teenage years and finally into adulthood too. In college, as Rajasthan’s Best Cadet for the National Cadet Corps at the Republic Day Camp, she had spent two cold wintery months in New Delhi, marching to this song along with Sare Jahan Se Accha. Birla Balika Vidyapeeth’s All Girl Band too played it as did the Maratha Light Infantry Silver Band. Everyone around her seemed to be humming it. While Shodashi barked orders to her girl contingent, leading from the front; platooooooooon daaaaaaayine deeeeekh… ek do … (salute), she pictured herself a war heroine battling enemies at the border. Her military stint did not last long, she, having failed the Service Selection Board which had opened up for women a few years later. You are not made for the military, you have to say yes sir no sir for everything, you are not cut out for this, it is for the best, Shodashi’s father was happy that she had not landed in the IAF, one was enough. Her mother meanwhile mourned the lost chance to continue her life in the Forces, which Shodashi also agreed was glamorous, adventurous, dangerous, a far cry from the staid civilian’s.

It was twenty years before she thought of that tune and that film again. In Colombo, Sri Lanka, when their tour guide had offered to take them to Mt. Lavinia and then to Kitulgala to show them where the film Bridge on the River Kwai was shot, Shodashi had jumped at the offer. Oh! Wow this is what the POWs built, is it! By now she knew the acronym meant Prisoners Of War, and that they were forced to build this bridge on the railroad in Burma. But how could there be a railroad from Sri Lanka to Burma, this seemed improbable. Sri Lanka is an island. That is when the guide sheepishly revealed that this was not the actual spot where the real incident had taken place but merely a place of filming by David Lean. The bona fide bridge was in Thailand. Thailand? Well geographically it made much more sense. One could definitely build a bridge and a railroad connecting Thailand to Burma.

And another twenty years later, her Thai tour guide disabused Shodashi of some more misinformation. “This bridge was bombed by the Allies not by the Japanese as shown in the film”, he announced to a perplexed group, indignantly. “In fact the current bridge had been rebuilt with the help of the government of Japan, a constitutional monarchy, Buddhist just like us”, he stressed the word monarchy with pride which seemed to convey a slight disdain for democracy. Or so Shodashi thought. Her gut was usually right as she spotted a smirk on the guide’s face when he looked at his audience; an Indian, four Kiwis and two Scotsmen.

Getting into the van where Shodashi and others were seated, a small eight seater, he sound tested his mike, although there was no need to use it except to look professional; You will be allowed to walk across the Bridge on the River Kwai, and take as many photos as you wish. It will be a once in a lifetime experience. We will drop you at the train station and you take the train - over the bridge, and into the hills, and beautiful forests of Kanchanaburi, on the Death Railway. Our van will pick you up at the end point after a sumptuous lunch. Please stick together. If you are lost, we are not responsible”. With that somber note, he nodded at the driver to start the van, which spluttered a bit at the beginning but picked up speed as it hit the highway. The tour guide Chakri had said all this in his thick Thai accent, while the young tourists looked at one another a bit confused, so Shodashi mouthed the words to them silently. She could comprehend him without much difficulty. Indians speak so many different types of English, each state has its own accent. It was normal for people to adapt the accent of their mother tongue when they spoke any other language.

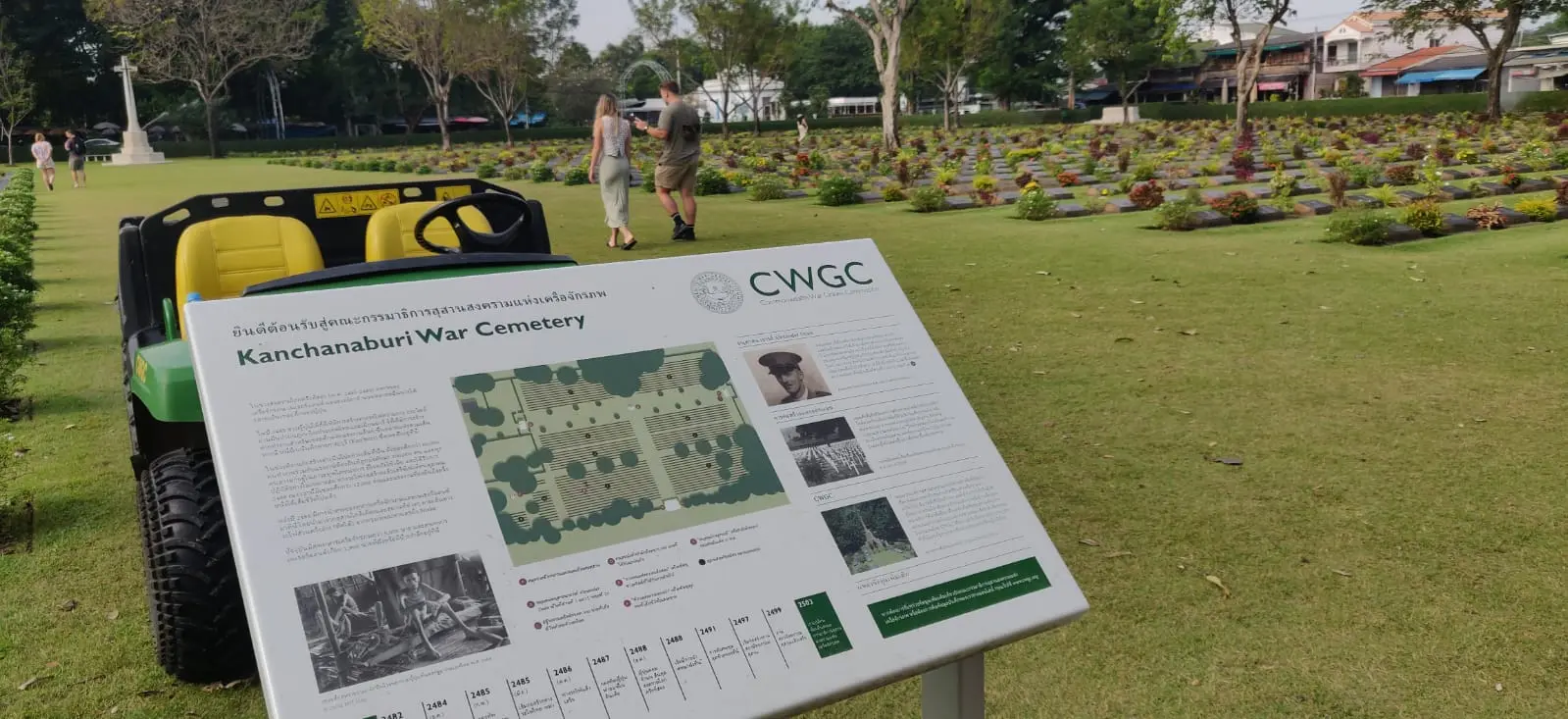

Chakri did not have to sell the tour to Kanchanaburi so much. Shodashi had sought this trip out, wanting to make real her promise to herself from forty years ago. The city itself was a charming town with lampposts and trees flanking the central boulevards. Bus loads of tourists were either alighting to take a peak at history or leaving after being sombered by the tragedy that was the Death Railway. School children were on a field trip to the Kanchanaburi War Cemetery situated adjacent to Saeng Chuto Road, to write an essay on their learnings. They wandered about listlessly without any interest, why would they be keen on something that took place so long ago in history. What do I care, they seemed to be saying mutely, under the close watch of their minders.

Shodashi too wandered about with this very thought in mind: Why do we wage wars? Even while reading, she was someone who had skipped the War sections and gobbled up the Peace parts of Tolstoy. Her father, a true soldier through and through, would not brook such nonsensical romanticism taking root in his own house: “...who will protect you when someone attacks your house, your shop, your neighbourhood, your elders, women, children, your country and your borders?...” This was his favourite topic in Air Force Station, Jaisalmer, Rajasthan. Convincing Shodashi and her rag-tag group of high school friends, all boys, woolly eyed teenagers, that war was necessary to root out evil. Remember how much Krishna begged and begged Duryodhana to let the Pandavas be… did he listen? Did he listen? DID HE? NO SIR! Shodashi’s classmates came home most evenings to listen to her dad and not really for her, this angered her somewhat but she was also a bit pleased, especially when they hung onto her father’s every word and answered in unison, mesmerized. No Sir!

All of them watched Mahabharata by B.R.Chopra on Doordarshan diligently. Shodashi of course could not be bothered. She had her NTR nee Krishna from the Telugu mythologicals, the sets and costumes of which were far superior, and the language closer home. She knew all the plots and subplots from the Krishnavatara series by K.M.Munshi that her father had gifted her for 10th standard board results, and was exasperated when her classmates did not know the nitty gritties from the itihasas; you mean to say you do know who Shaibya is? Or even Uddhava? ...aur gaayo ek do teen...tcha!

The road to Kanchanaburi, or the land of gold, Kanchanapuri, was not too far from Bangkok. The reception desk was offering various day trips, and Shodashi decided to take one up, chucking her driver who had taken her to Ayutthaya the previous day. It would be good to have some company for such a trip, it was not of spiritual or religious value as such, on the face of it. She wanted to break the mould and do something different and this was long pending, forty years in the making. Historical tours also attracted very few Indians for some reason and here she was with unknown faces snaking through green mountain ranges and deep dark valleys, chugging along great rivers, and crossing mountain passes. This is where work began in 1942 on June 22nd, in Kanchanaburi, which is about 140 kms from Bangkok, to the West, towards Burma, all the way to Thanbyuzayat in the south of Burma. All of 415 kms with about 60,000 pows of the Allied Forces being commissioned to work on this Siam–Burma railway line. So much has changed since, those two countries do not exist anymore, now we have Thailand and Myanmar.

The van as promised had come to pick her up from her hotel at 6.00am in the morning, the lady chef at the cafeteria had made sure she had a packed breakfast ready, and Shodashi got herself ready by not researching anything today. She wanted to go at it spontaneously, let me see how this decades long dream will come to fruition. How will it unfold for me? The next day she would be returning to Hyderabad. Her van mates were two couples from New Zealand and one gay couple from Scotland. Before long everyone was chatting with one another, getting to know the lay of the land, cracking jokes, sharing touristy information. The advantage of travelling with non-Indians is anonymity. One need not reveal everything to strangers and there is no fear of them figuring you out with standard cultural clues - you are free to be anyone, or no one.

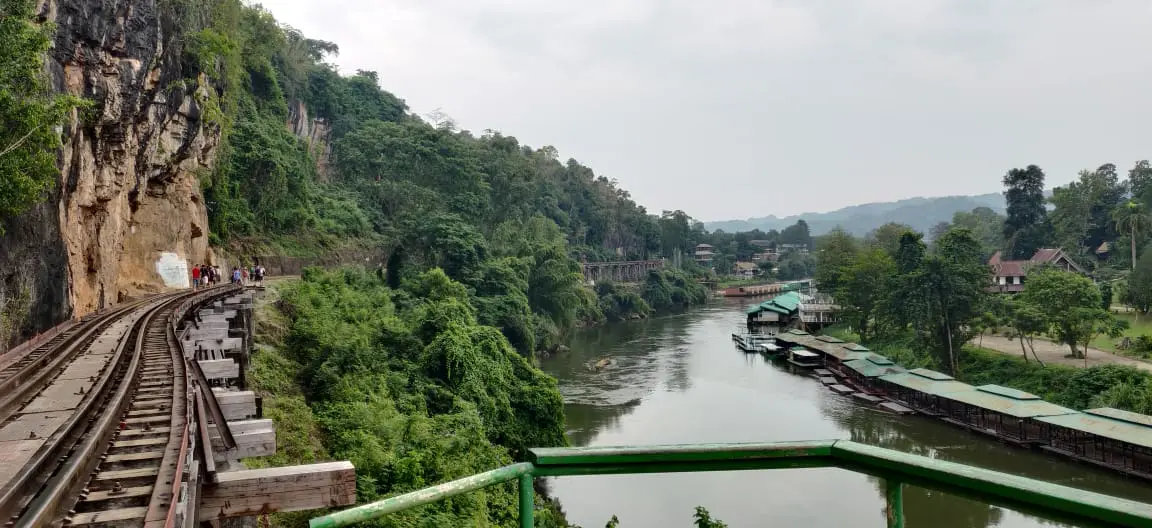

It was indeed an unforgettable experience. Shodashi sat dangling her feet into the valley, in front of her lay the Khwae Noi, gurgling gently and curving its way to the Gulf of Thailand. The restaurant which catered to the railway day trippers was jam packed and the buffet was humongous with fruits, drinks, snacks, meals, salads, all on display in this wooden building right on the ledge, overlooking the river. Behind it was the railway line, hugging a vertical jagged cliff. There was nothing else to buy or nowhere else to eat except at this one. The chef rose to the occasion though and Shodashi was fed with a ‘sumptuous lunch’ as promised and vegetarian too on the asking. While she waited, she sat at the edge, looking down at her feet that were freefalling in space. The sudden bursts of wind broke the humidity, the loud chatter of other travellers kept her in the moment. They had all just gotten back from the Cave a few feet away which was carved into the cliff, and a large Buddha had welcomed them inside with fresh orchids and incense. The Wang Pho or Wampo Viaduct lay before them in all its glory.

Shodashi sat silently while she bided her time for the meal to arrive. She did not worry about what she would eat, what they would offer her, or if they could manage something vegetarian at all. She did not worry about tomorrow when she would be returning to Hyderabad, India. She did not think about family, friends, or colleagues. She sat silent. She waited in silence. Silently she breathed in and out, softly, slowly and gratefully. Thom Kra Sae. This is where Shodashi is, in the now.

The Bridge on the River Kwai has been crossed.

Shodashi would have loved to go all the way to Burma on the Death Railway, but it had now been pulled apart section by section, just as it had been put together all those years ago, mile by mile, a handmade railway that caused death by the millions. The lawless jungles and the humid forests brought with them disease and hunger. Unable to fight the viruses or bacteria nor being able to find adequate food to eat, many succumbed to anonymity six feet under. Many mass graves were discovered once the World War was over.

Interestingly it was not just the Allied POWs but also many Tamizhs who had gone over to build this railway line on the invitation of the labour contractors who promised them great money. When it was clear that the POWs were not enough to complete the project in time, the Japanese started recruiting Indian Tamil and local Burmese labourers too, who were initially taken to work in the Malay rubber estates. These labourers were promised ‘good money’, and were taken to the southern part of Burma, the other end of the railway line to work towards its timed completion.

The hundred plus kilometre railway needed able bodied men who were used to this harsh terrain. But today there is no trace of those Tamizh and Burmese workers of the Death Railway, no monument dedicated to their lives or any book that talks of their struggle. Malaria was rife, maggots ate away at the wounds of warriors and commoners alike, there were no toilet facilities, no nutritious food nor access to proper medicines. Men were mostly clothed in loin cloths and became emaciated working under the tropical heat and in pouring rain. It was a tough task completing the bridge as many of the wooden structures that were put in place kept getting washed away by the floods. Many POWs perished unable to bear the hardships and were buried by the railway lines.

About 60,000 Tamizh and 30,000 Burmese labourers also died in making this railway line. But where were they buried, and were any of them cremated at all as per their religious beliefs? No film or documentary talks of these unnamed unsung people. No Hollywood or Bollywood movie has been made to glorify them.

The bridge though was completed in record time, within a year and half, by Oct 1943, when both lines, one from Siam and the other from Burma, met at Three Pagodas on the Siam-Burma frontier. Of course this occasion was commemorated and celebrated, like a festival with feasts and merry making. Chakri scoffed at our reverence for the David Lean film, ‘Bridge on the River Kwai’, calling it hogwash, you must watch authentic documentaries and films, read books that tell you the truth. Not this trash he repeated.

The notorious Burma-Siam railway, built by Commonwealth, Dutch and American prisoners of war, was a Japanese project driven by the need for improved communications to support the large Japanese army in Burma. During its construction, approximately 13,000 prisoners of war died and were buried along the railway. An estimated 80,000 to 100,000 civilians also died in the course of the project, chiefly forced labour brought from Malaya and the Dutch East Indies, or conscripted in Siam and Burma. Two labour forces, one based in Siam and the other in Burma, worked from opposite ends of the line towards the centre. The arched sections are original (constructed by Japan during World War II); the two sections with trapezoidal trusses were built by Japan after the war as war reparations, replacing sections destroyed by Allied aircraft. Lieutenant Colonel Philip Toosey of the British Army was the senior Allied officer at the bridge in question. Toosey strove to delay construction. He encouraged termites which were collected in large numbers to eat the wooden structures.

An American engineer said after viewing the Death Railway Project:

What makes this an engineering feat is the totality of it, the accumulation of factors. The total length of miles, the total number of bridges – over 600, including six to eight long-span bridges – the total number of people who were involved (one-quarter of a million), the very short time in which they managed to accomplish it, and the extreme conditions they accomplished it under.

And this is precisely why the railway line should have been left alone and maintained properly, so that there could be to and fro of goods and people, in the memory of those who gave up their lives to make this a reality. What a waste of hard labour if it had to be abandoned in such a callous manner!

Shodashi completed this last paragraph of her piece and sent it off to her publisher, humming the Colonel Bogey March written in 1914 by Lieutenant F. J. Ricketts (1881–1945), a British army bandmaster who later became director of music for the Royal Marines at Plymouth.

The man responsible for her forty year old dream and its fulfilment.