O royal skilled engineer, construct sea-boats, propelled on water by our experts, and aeroplanes, moving and flying upward, after the clouds that reside in the mid-region, that fly as the boats move on the sea, that fly high over and below the watery clouds. Be thou, thereby, prosperous in this world created by the Omnipresent God, and flier in both air and lightning.

Yajur-veda 10.19

We are the land of the samudra manthana, the ocean which gave us wealth and health - Lakshmi and Dhanavantri - among other fantabulous riches from its depths. We are the people who grew up on these stories of oceans, seas, and rivers. We then embraced them as our own and embarked on perilous journeys. Yet we know not of this grandeur.

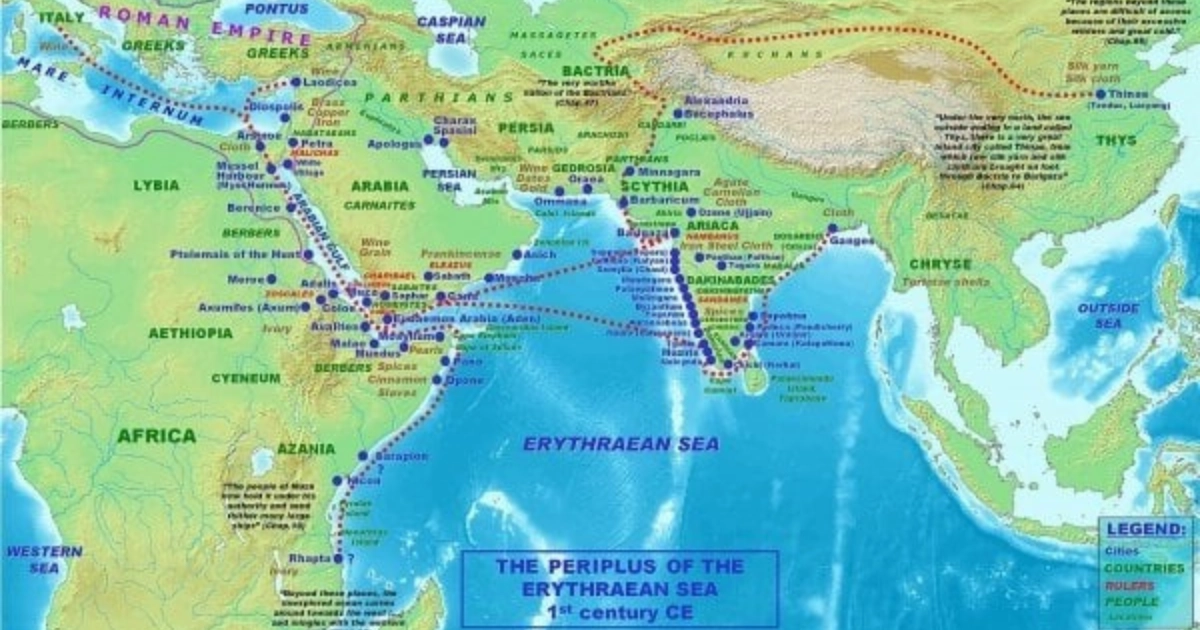

It was India, not China, that was the greatest trading partner of the Roman Empire. During this era, sea travel was the fastest, most economical, and safest way to move people and goods in the pre-modern world, costing about a fifth of the price of equivalent land transport, says historian William Dalrymple in his new book The Golden Road.

The chundan vallams of Kerala are a sight to behold especially during the vallamkali or boat races, held yearly in a grand manner during the monsoon months of June to September. Starting with Champakkulam and ending with the Aranmula Boat Race on the Pampa river for Onam, these races in and around the Alappuzha backwaters commemorate the kings of this region who indulged in such competitive races. The boats are sleek, running upto 120 feet in length, with as many paddlers in the canoe, which is snake like, with a hood or the stern rising four to fifteen feet above the water. Accompanied by vanchipattus or boat songs, these races hark back to India’s great maritime heritage - be it inland on the rivers, backwaters, or on the seas, across the Indian Ocean.

As with all Indian Knowledge Systems (IKS), there is a connection to the divine, there is a well designed methodology to interlink life and philosophy via mundane activities made sacred. One kind of such boats are the palliyodams which are unique snake boats built by the Aranmula Parthasarathy Temple in Pathanamthitta district for their temple rituals, divine vehicles that carry the temple deity. They are said to be designed by Lord Krishna himself, while the temple itself is said to have been consecrated by Arjuna. Made of wood from the jackfruit tree, they carry 64 paddlers representing the 64 kalas. Four rowers at the end represent the 4 vedas, and the 9 golden shapes at the end of the palliyodam represent the navagrahas, accompanied by singers of course. There is a prescribed diet, ritual, and dress code that all the males who row the palliyodam have to adhere to.

The one aspect that all of them adhere to and cannot do without; to win a race, or simply move ahead and glide on the waters, is rhythm, the taalam of life.

Given such a grand heritage where IKS, religion, sports, and adventure are linked so seamlessly, the proposed lecture on, “India’s Maritime Traditions and Recreating the ‘Stitched Ship’”, came as a fitting and timely tribute to our exceptional abilities on water.

Listening to Shri. Sanjeev Sanyal, author, historian, economist, and currently a Member of the Economic Advisory Council (EAC) to the Prime Minister, speak on his project of reviving the Indian Stitched Ship, at a presentation organized by Indian Institute of Technology (IIT) Heritage Science and Technology, at Hyderabad, in their Heritage Talk Series, got everyone’s adrenaline running. The audience was agog with excitement. It is not often that youngsters can lean into a topic on campus that allows them to give vent to their adventurous dreams. Their lives are usually about doing well in academics and then securing a cushy job. To hear an economist, a senior bureaucrat at that, speak with such passion on something that was as multidisciplinary as it was out-of-the-box, shook them from their postprandial slumber.

If we notice any Indian beach, say the Marina Beach in Chennai, most onlookers don't even swim out into the ocean, they simply stand and look, enjoying the waters from afar. Yes, it is rough seas, yet. How come surfing or other adventure sports have not caught on around the beaches in our country. This is because of the dormant knowledge in us; which reveres the ocean waters as Varuna devata, who is sleeping and must not be disturbed. We look upon ocean waters as sacred, as all else, and only certain days do we touch him or take a holy dip. This behaviour plays into sustainability and ecological awareness of current times, but naysayers will end up calling it superstition.

Given such intergenerational memories and taboos, many of us might assume that adventure is not a dharmika activity, that it is forbidden by the many rules and regulations, vidhi nishaedhas, of shastra. It is not so. Given that we are made of the panchamahabhutas, it is but natural that we feel an affinity with the elements of nature. When we happily get drenched in the rain or prance about in the flowing streams, when we cannot take eyes off of a bonfire, when we let the wind blow our worries away, when we play with earth and get our hands all muddy, when we look up at the sky and sigh at the sight of the stars, that is us acknowledging our physical ancestry, a nod to the samashti from the vyashti.

It is after all bhagavan’s leela, this world, which is so full of beauty and wonder. And to experience it is to be in tune with the highest principles of sanatana dharma. Our various yatras designed such that we traverse the length and breadth of the Indian subcontinent is a testament to this fact.

Then how do we reconcile the fact that there are many injunctions preventing us from crossing the ocean, from playing in the ocean waters at random, from going all out and headlong into any expedition which is fraught with danger and surprise?

Firstly the injunctions were mainly for brahmanas who were custodians of the scriptures and also role models of living a refined and cultured life. One could not expect them to follow shastra, which required them to stay put in their own spaces near a temple or in the vicinity, and also go out for months on sea faring escapades. That would be antithetical to their jati dharma. Their travel was the yatras they made for darshan and adhyayanam. If there are a significant number of Tamils and Telugus in Kashi, it is because they traveled there to study under a guru. It is common to find the surname Varanasi or a Kashi Annapurna among Telugu Brahmins even today. But that was the limit of their travels. Nor could the kshatriyas run off on will to tick off a to-do tourist list. They had their land and people to protect. Of course they did get to travel when on military conquests, although Indian kings rarely ventured away from their own territories within the subcontinent.

The ones who did not come under any such travel ban were definitely the vaishyas, the merchant class, and also the shudras; the artisans, and craftspeople. Just as today we have people crossing the seas for IT jobs who provide software services, so too in our history we have had entrepreneurs and service providers go to exotic places leaving the comfort of their homes far behind to offer what they could - textiles including silk, perfumes, unguents, balms, pigments, dyes, salt, spices, gold, precious stones, minerals, metalwork, ivory, elephants, exotic animals, and other such goods.

Along with them went Hindu and Buddhist thoughts, philosophies and mores. Brahmi, the written script, reached the shores of Thailand and Indonesia via such voyages. And Sanskrit rode the waves with these seafarers to find its home in far flung Japan and even China. With language went mathematics, astronomy, aesthetics, and the whole knowledge system. Some brahmanas might have broken the interdiction of crossing the seas in order to sacralize these lands with temples and rituals, thus helping in pushing the boundaries of sacred Bharata far beyond its traditional shores. Evidence of this is found in services offered by Hindu brahmanas both in Thai and Cambodian royal courts. Evidence of this is in cities named Ayutthaya and rivers named Ganga in these distant lands.

Hindu dharma spread far and wide both Westward to Middle East and Europe; Oman, Muscat, Yemen, Tanzania, Ethiopia, Egypt, Italy, and Eastward to Thailand; Indonesia, Malaysia, Philippines, Japan, China. This was possible without waging wars, via trade of which Shri. Sanjeev Sanyal writes extensively in his books on India’s maritime trade and history such as the Ocean of Churn, of how our geography shaped our history.

Yet, we have not produced an Ernest Shackleton or a Thor Heyerdahl. How come we do not have our own version of Sindbad the Sailor, or the Gulliver’s Travels. There is no Indian Captain Haddock or Popeye in our collective memories. We do not have our version of the Pirates of the Caribbean. If we did indeed have such heroes, they have not captured the public’s imagination and are largely unknown.This despite Bharat being the frontrunner in boat and shipbuilding.

Going by historian accounts; Ptolemy writes that the Indians built a fleet of 2000 ships, some of which could accommodate a 1000 troops along with horses and vast supplies. Marco Polo says Indians built large ships which accommodated 300 and more men, with 60 plus cabins. Nicolo Conti records that these Indian ships were of 1000 tons each with 5 sails. All oceanic voyages were invariably funded by Hindu temple banks, which also explains how many temples ended up having so much treasure in their vaults.

The Muziris Papyrus gives us ample proof of India's trade with the West. From the Gupta period i.e., from the 3rd century C.E onwards, we have proof of foreign travel on large barges carrying cargo for trade, which made its way all the way to Rome. The Mauryans even gave tax incentives to its citizenry for shipbuilding! One of the oldest pieces of evidence of stitched ships is from a Sanchi sculpture, from the 2nd century C.E. We have sailed to far off lands on a yearly basis on these indigenous boats. The Bali Jatra of Odisha or the Boita Bandana is but a cultural way to keep that memory alive of men sailing off to far lands, while the women and children awaited their return eagerly. These sailors and merchants would go to Ceylon, to Sumatra, to Bali. From there they sailed to farther lands, as far away as the ocean waters, the winds, and currents took them, and returned once the winds and currents changed direction and they could sail towards India easily. Their boats would carry upto seven hundred men and animals. Kalidasa in his Raghuvamsa refers to the King of Kalinga as ‘The Lord of the Sea’. The bhoga mandapa of the Jagannatha Temple too has a bass relief of a stitched ship, showcasing the deep Odiya involvement with seafaring. Interestingly the rituals of Boita Bandana are very similar to those of Loy Krathong of Thailand, signaling a shared heritage and with a shared maritime past.

The Yukti Kalpataru, an ancient treatise on boat building written by Raja Bhoj classifies various types of ships that were built in India. These could be stitched together or nailed, with a length that was four times the breadth, i.e., with a ratio of 1:4. They were usually 80 mts long with various cabin structures.

We are often told that the needle came to India via the foreign invaders, but if we have been stitching ships with needles since the 3rd century. C.E. and we were also a power house in metallurgy (the Mehrauli Iron Pillar at Delhi is a good example of Indians knowing rust-free iron technology), we might have to revisit this claim that we were unaware of the iron needle.

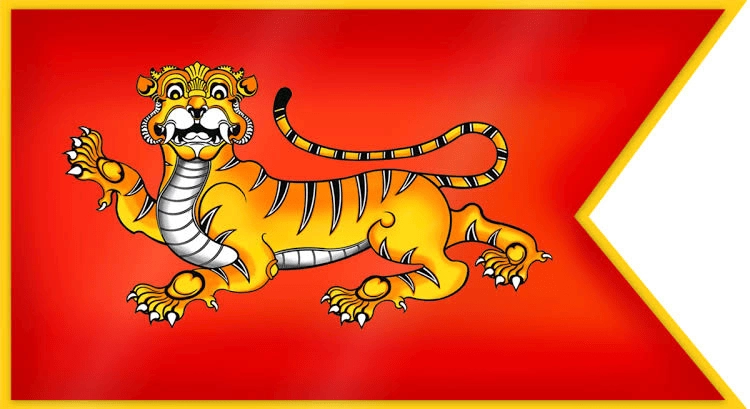

We stitched the ship i.e., we stitched the steamed planks together. Planks were first steamed because these made the hulls more flexible, they did not break easily and were less prone to coming apart when they struck atolls, reefs, shoals, and sandbars in the Indian Ocean, where the sea was at its roughest. Geographically reefs occur near Maldives or Lakshadweep. A stitched ship might leak but it would not go to pieces if it hit upon them in inclement weather. We also did not nail the boats as it would ‘hurt’ the wood. Nailing would deteriorate the quality of the wood. Although once cannons were introduced, it was better to adopt the nailed ship technique as the blowback from the cannons was not easy on a stitched ship. Hence the Maratha Navy too moved from stitched ships to nailed ships. Their octagonal design is now used officially by the Indian Navy in its new ensign.

Although a few families have managed to keep the knowledge of building the stitched ship intact, this 2000 year plus history of the stitched ship from India, has no takers in the modern world. Currently only a few fishing boats use this technique on both the coasts. To help revive this technique, to learn more about our maritime history, and to see if we can re-enact the naval glory of yore, to invoke pride in our heritage where ships sailed guided only the stars, using the sails dexterously as per the monsoon winds and currents, this project was conceived and is currently underway.

Lead by Shri. Sanjeev Sanyal, and assisted by the Ministry of Culture, Ministry of External Affairs, Ministry of Defence, and Ministry of Shipping, this unique idea of building an ancient ship and sailing it will take off next year. Commander Y. Hemanth Kumar, a qualified naval architect from the Indian Navy, has been instrumental in seeing this project through from his end. Harappans have traded with Oman Peninsula since ancient times, sailing off from the Gujarat coast and using the monsoon winds and currents to their advantage. By recreating those journeys without the use of modern technology, on an indigenous stitched ship no less, we can finally have our own Kon Tiki moment.

Babu Sankaran is one of the few boat builders who can stitch boats today. Hailing from Kerala, the Beypore area, he and his team will help build this ship under Project Mausam. With needles of course, and coconut fibre which is used as filters for joint and gaps, using kundrus resin or shallaki gum which is critical for the gaps, as it hardens and fills the holes, also used is fish oil, along with limestone powder, cotton, coconut, and finally a red brick pigment for the hull and external ship for durability.

This knowledge of stitching ships is passed down from generation to generation with skill and experience. Unfortunately, children of these communities are no longer following this profession and it is a dying technique. Babu Sankaran’s son though after noticing the interest that the Indian Government took in this project, and how his father was felicitated for such precious knowledge by the Indian Navy, is now back to learning this technique, after having left it to pursue other avenues. This ship is being built at Hodi Shipyard, Divar Island, Goa.

Once the ship is made and is tested, once it sails to Oman and returns safely, it will be ready for the Bali Jatra on Kartika Poornima, and after returning from that, the stitched ship along with the whole documented journey from start to finish will be housed in the Maritime Museum at Lothal.

How to Build a Stitched Ship:

- Keel is usually laid first, from single piece of timber, preferably.

- Planks are then taken and steamed. Steamed planks are used which helps to get desired shapes.

- Steaming loosens the fibers of the wood and hence it can be shaped easily.

- Outer shell i.e. the hull is now created.

- Holes are drilled on the two planks.

- Coconut fiber is laid out over the joints of planks for wadding and layered with coconut coir ropes.

- Coir ropes stitch the wads of fiber and planks together.

- Kundrus resin is then applied to the planks.

- Wadding is hammered down and coir rope is pulled through the holes.

- Stitching is done in the I I X I I pattern.

- Next, the frame is stitched to the plank.

- Stem post and stern post are stitched to the keel.

- Horizontal cross beams are stitched together.

- Stitching holes are filled with plugs.

- Putty applied on the holes.

- Coating of fish oil is done inside and outside the hull.

This particular ship will follow the design elements similar to a painting from the cave #2 at Ajanta, it will also reference the ancient texts on ship building as well as the Omani reconstructions made by Babu Sankaran himself. Trailing oars in place of central rudders will be retained from the traditional design, as also the square sails, not the triangular sails which are more common now. One captain and 12 sailors will man this stitched boat, which will include Shri.Sanyal. The boat will be finally named once it enters the waters and is ready to sail, and not before.

Once the expedition to Oman is successful in the prescribed time of three weeks, the plan is to sail to Bali, which will take longer. Odisha to Bali is a longer route - not directly across Bay of Bengal, as the square sail sails along with wind; so first to Sri Lanka via Kalingapatnam, and then maybe a stop at Nagapattinam, to Trincomalee, and then onwards to Northern Sumatra, and then using cross oceanic currents in the Indian Ocean - which are different from Pacific and Atlantic being of slow steady speed, to Bali. Using local wind patterns of 10-15 knots, with wave heights of 1-2 meters, our sailors will be up and about on the high seas, just as many moons ago merchants with goods and men reached far off lands exchanging ideas and mores.

Currently in house research and testing is going on. A 3D model of the hull form using computational fluid dynamics modeling has been created. The hull has to be tested in a hydrodynamic towing tank for seaworthiness, and since IIT Madras has a towing tank, that is where this will be tested. In the land of the Chozhas.

Chozhas, who put together the first blue water maritime force - a naval force that operates beyond its shores with offshore bases - followed the mass migration of the turtles all the way to South East Asia, leaving their mark in the grand temples of those lands, their architecture and customs, which have lasted to this day. Imagine if we had made these brave seafaring warriors household names. We would be singing their tales of bravery, indomitable spirit, and great adventure to this day!

We forget India is a peninsula. The nau khelas of Assam and their gaan hold a lot of similarity with that of Kerala. Our attention and gaze must be waterwards if we are to give the fast dying traditions a fillip. From the shikaras of Kashmir, to the kettuvallams of Kerala, from the naus of Assam to the kutchchi boats of Gujarat, there has been an enduring legacy of the waters that connects ritual, religion, culture, sport, economics and ecology in a seamless fashion, both in country and abroad. We must be worthy custodians of this grand heritage.

Let us hope that through this oceanic venture, we too will learn the modern applications of such an arduous journey, the economic possibilities, and the new learnings. At the very least, such a feat will bring back the joy of adventure, and rebuild a culture of sailing in our country which has lost so much of its rich heritage already. This project will make us sensitive to our environment and ecology too. It will help us keep our water bodies clean.

We must remember to do a lot of storytelling around this event when it happens, to make our own maritime movies, naval novels, and comic books, to leave a legacy of the waters, of high-sea heroes.

And on that note -

dhit dhit taara

dhit dhit tai

dhit tai

tak tai tai tom!കുട്ടനാടൻ പുഞ്ചയിലെ

തെയ് തെയ് തക തെയ് തെയ് തോം

കൊച്ചു പെണ്ണെ കുയിലാളേ

തിത്തിത്താതി തെയ് തെയ്

കൊട്ടുവേണം കുഴൽവേണം കുരവവേണം

ഓ തിത്തിത്താരാ തിത്തിത്തെയ്

തിത്തൈ തിത്തൈ തകതെയ്വരവേൽക്കാനാളു വേണം

കൊടി തോരണങ്ങൾ വേണം

വിജയശ്രീലാളിതരായ് വരുന്നൂ ഞങ്ങൾ

ഓ തിത്തിത്താരാ തിത്തിത്തെയ്

തിത്തൈ തിത്തൈ തകതെയ്കറുത്ത ചിറകു വെച്ചു

തിത്തൈ തക തെയ് തെയ് തോം

അരയന്നക്കിളി പോലെ

തിത്തിത്താരാ തെയ് തെയ്

കുതിച്ചു കുതിച്ചു പായും കുതിര പോലെ

ഓ തിത്തിത്താരാ തിത്തിത്തെയ്

തിത്തൈ തിത്തൈ തകതെയ്തോൽ വിയെന്തെന്നറിയാത്ത

തല താഴ്ത്താനറിയാത്ത

കാവാലം ചുണ്ടനിതാ ജയിച്ചു വന്നൂ

ഓ തിത്തിത്താരാ തിത്തിത്തെയ്

തിത്തൈ തിത്തൈ തകതെയ്കുട്ടനാടൻ പുഞ്ചയിലെ

കൊച്ചു പെണ്ണെ കുയിലാളേ

കൊട്ടുവേണം കുഴൽവേണം കുരവവേണം

ഓ തിത്തിത്താരാ തിത്തിത്തെയ്

തിത്തൈ തിത്തൈ തകതെയ്പമ്പയിലെ പൊന്നോളങ്ങൾ

തിത്തൈ തക തെയ് തെയ് തോം

ഓടി വന്നു പുണരുന്നൂ

തിത്തിത്താരാ തെയ് തെയ്

തങ്കവെയിൽ നെറ്റിയിന്മേൽ പൊട്ടു കുത്തുന്നൂ

ഓ തിത്തിത്താരാ തിത്തിത്തെയ്

തിത്തൈ തിത്തൈ തകതെയ്

തെങ്ങോലകൾ പൊന്നോലകൾ മാടി മാടി വിളിക്കുന്നു

തെന്നൽ വന്നു വെഞ്ചാമരം വീശിത്തരുന്നൂ

ഓ തിത്തിത്താരാ തിത്തിത്തെയ്

തിത്തൈ തിത്തൈ തകതെയ്കുട്ടനാടൻ പുഞ്ചയിലെ

കൊച്ചു പെണ്ണെ കുയിലാളേ

കൊട്ടുവേണം കുഴൽവേണം കുരവവേണം

ഓ തിത്തിത്താരാ തിത്തിത്തെയ്

തിത്തൈ തിത്തൈ തകതെയ്ചമ്പക്കുളം പള്ളിക്കൊരു

തെയ് തെയ് തക തെയ് തെയ് തോം

വള്ളം കളി പെരുന്നാള്

തിത്തിത്താരാ തെയ് തെയ്

അമ്പലപ്പുഴയിലൊരു ചുറ്റു വിളക്ക്

ഓ തിത്തിത്താരാ തിത്തിത്തെയ്

തിത്തൈ തിത്തൈ തകതെയ്

കരുമാടിക്കുട്ടനിന്ന് പനിനീർക്കാവടിയാട്ടം

കാവിലമ്മക്കിന്നു രാത്രി

ഗരുഡൻ തൂക്കം

ഓ തിത്തിത്താരാ തിത്തിത്തെയ്

തിത്തൈ തിത്തൈ തകതെയ്കുട്ടനാടൻ പുഞ്ചയിലെ

കൊച്ചു പെണ്ണെ കുയിലാളേ

കൊട്ടുവേണം കുഴൽവേണം കുരവവേണം

ഓ തിത്തിത്താരാ തിത്തിത്തെയ്

തിത്തൈ തിത്തൈ തകതെയ്

Footnotes:

- Most of the material on the Stitched Ship for this article came from Shri. Sanjeev Sanyal’s presentation at IIT HST, Hyderabad on Aug 14 2024.

- Cover image is taken from here.