This article uses the ISO 15919 standard of diacritization for Tamizh words.

The Print published an opinion piece on the Tirupati laddu row, written by Anirudh Kanisetti, titled ‘Tirupati god was originally offered pongal. North Indian pilgrims brought laddus’ (September 24th, 2024). The primary thrust of Kanisetti’s piece is that Tirumala was once a minor shrine only exalted by local devotees and grew as an “investment destination” for the Vijayanagara elite in the 16th century. The aforementioned and other erroneous claims made in his article will be addressed here in this piece.

Kanisetti’s article is a not-so-subtly executed attempt to portray Vēṅkaṭādri as a shrine of limited influence and popularity prior to the modern era, and an elitist Śrī Vaiṣṇava institution — only held sacred since the 9th / 10th centuries — and only patronized by the Brahminical elite and the various large kingdoms of Southern India. But a multitude of Saṃskṛta, Tamizh and Telugu literary evidence paint a picture of the sanctity of Śrī Mahāviṣṇu for centuries prior.

To begin with, the sanctity of Vēṅkaṭācala Hill is attested to in multiple Purāṇas: the Skanda, dated to circa 5th to 8th century, the Varāha, Vāyu and Viṣṇu composed perhaps between 350 and 750 CE, among others. Sri Vēṅkaṭācala Māhātmya, a recurring section found in the Varāha, Skanda, and Bhaviṣottara Purāṇa etc. describes the opulence, sublimity and divinity of the sacred hill, and recounts the descent of Śrī Mahāviṣṇu from Vaikunṭham to Vēṅkaṭādri.

In classical and medieval Tamizh works, the hills of Vēṅkaṭam formed the northern boundary of the Tamizh-speaking regions (as seen in Akanāṉūṟu 211 or the epilogue of the Cilappatikāram). Specifically, in the first canto of the Madurai Kāṇṭam of the Cilappatikāram, the Tamizh Saṅgam epic dated to circa 2nd century, recounts Kaṇṇaki and Kōvalan’s conversation with a pilgrim who was traveling hundreds of kilometers to Śrīraṅgam and Tirupati to see Lord Viṣṇu. When asked what brought him there, far from his native place of Mānkāḍu, he describes the iconography of Vēṅkaṭa. He states that he came to see:

...the beauty of the red-eyed Lord, holding in His beautiful lotus-like hands the discus which is death to His enemies, and also the milk-white conch; (to see Him) wearing a garland of tender flowers on His breast, and draped in golden flowers; and dwelling on the topmost crest of the tall and lofty hill named Vēṅkaṭam, with innumerable waterfalls, standing like a cloud in its natural hue, adorned with the rainbow and attired with lightning, in the midst of a place both sides of which are illumined by the spreading rays of the sun and the moon.

Vēṅkaṭam is one of the 108 Vaiṣṇava divyadeśas, or sacred sites of Vaiṣṇavism, established and celebrated in the hymns of twelve Āzhvārs, mystic saint-poets of Tamizh Nadu. The Āzhvārs' references represent a sacred geography that was navigated and chronicled, establishing a continuity of worship from their time to the present. The Lord of the Hill features heavily in the poetry of the Āzhvārs, second only to Śrīraṅgam in the number of verses written in its praise — a total of 202 verses. Vēṅkaṭam holds special significance within Śrīvaiṣṇavism. Nammāzhvār (late 8th – early 9th century) writes that on this vast earth, Viṣṇu is in Vēṅkaṭam, where the gods go to pray. Nammāzhvār surrenders to Śrī Vēṅkateśvara (prapatti) in the Tiruvāymozhi (VI.10):

You took the whole world

into your enormous mouth, towering lord

of undying fame, radiant body of everlasting light,

my precious life, a lovely mark on the brow of the world,

my great master of TiruVēṅkaṭam

I come from a long line of devotees

show me the way to your feet. VI.10.1‘I won’t part from you for an instant’

says Śrī who rests on your chest,

lord of matchless fame,

holder of the three worlds

my king, master of Vēṅkaṭam

dear to peerless immortals and sages

with nowhere else to go, I’ve settled at your feet. VI.10.1

translation by Archana Venkatesan

Peyāzhvār (6th century) in his Mūṇṛām Tiruvandādī, recorded his fondness for Tirupati:

As Lord, earth, the eight corners,

As Vedas and their meaning, as sky,

This Lord of Vēṅkaṭa with flooding waterfalls

Is also in our hearts.

Local tradition connects Vēṅkaṭeśvara with both the Toṇḍaimāns of the northern Coromandel and the Chozha kings as early as the 9th to the 13th centuries. In the 11th- 12th centuries, an impactful internal reorganization and a shift in the metaphysics of Tirupati, to be centered around Śrīvaiṣṇavism of Rāmanuja, brought Tirumala to even greater eminence.

Kanisetti writes that the earliest mentions of the god are from Tiruchanur, where the “only offerings made to Vēṅkateswara were ablutions of water and lamps filled with pungent sheep’s ghee.” In general, the use of sheep’s ghee is unheard of in temples or for ritual purposes, then or now. Sheep’s ghee finds no mention in any of the inscriptions in the source cited by Kanisetti. In addition, whether it is a pungent substance or not also requires corroboration.

Kanisetti also states that “[f]rom the 11th century, the Cholas unleashed conquests across southern India and lavished Tamizh temples with captured war loot, leading to innovations in ritual practices: the procession of bronze idols, the institution of calendrical festivals.” Firstly, there is no evidence to support the characterisation of Chozha donations to the temple as “war loot”, even if the timing coincides with war or conquest. Donations by Chozha kings were indirect, mostly made through vassals, emissaries, or treasurers, in the form of continuous endowments in perpetuity for the service of dharma and cannot be traced to war booty.

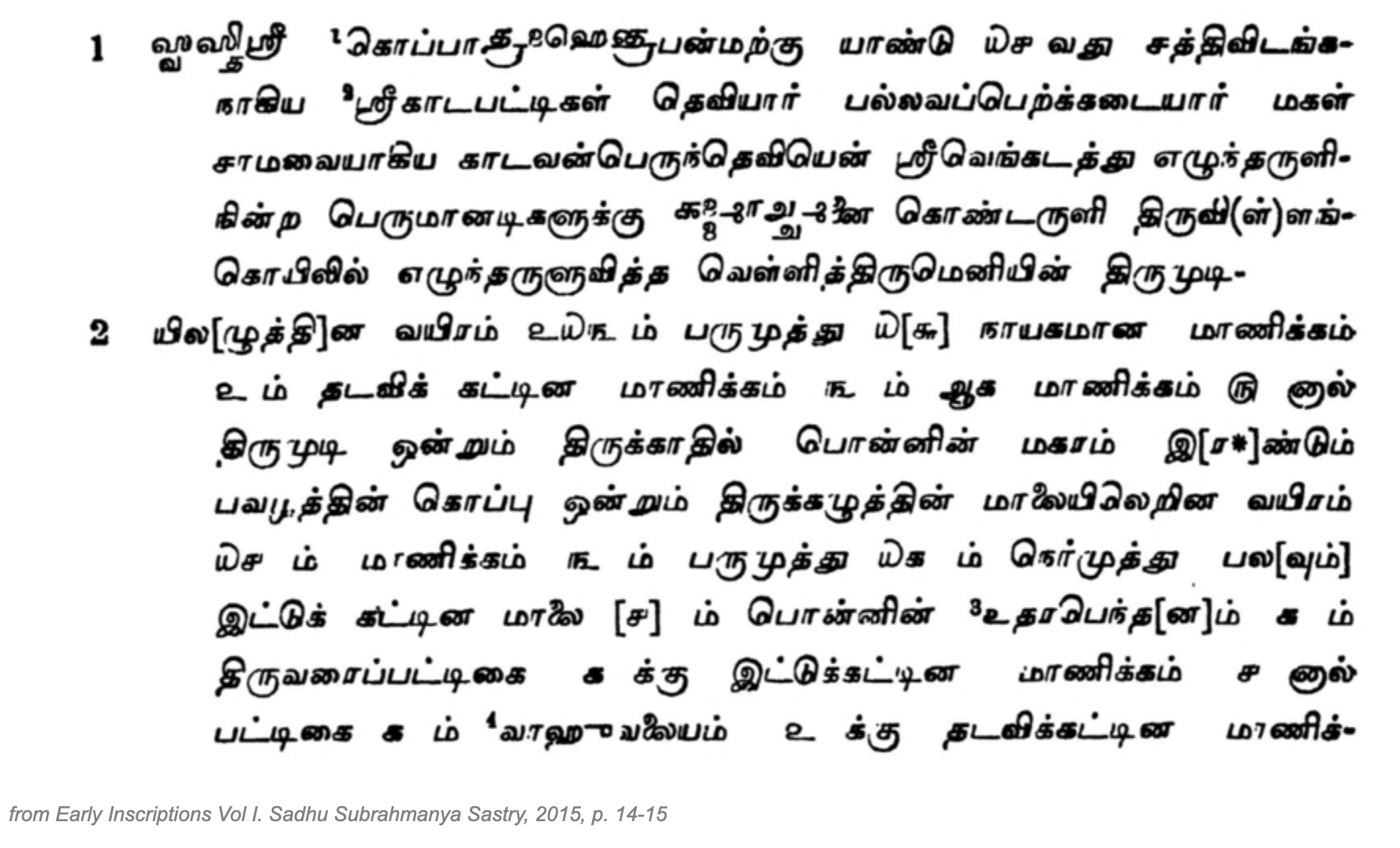

Second, two Pallava inscriptions on the north wall in the first prākāra of the Tirumala Temple state evidence of the consecration of a silver utsava mūrti (processional image) of Vēṅkateśvara, in 614 AD by the Pallava queen Sāmavayi, and the institution of special festivals and processions for these images twice a day for a period of seven days — later extended to twelve days — therefore pushing the date of the institution of processional metallic images back several centuries earlier than stated by Kanisetti.

The other major trope stressed by Kanisetti is the manner in which kings, especially the Chozha and Vijayanagara, and patrons such as temple officials viewed donations as “investments”. He writes, “[g]ifts to the temple were meant to be invested, and the accrued interest was spent on offerings”. The use of the word investment for an endowment or a donation is insidious and connotes that the donors expected dividends in return for the donation. This is not the case.

As gleaned from multiple inscriptions from Tirupati and from the general practice in temples across the country, endowments such as land and gold are made in order that revenue may be accrued by the temple in perpetuity, often to be used for a specific purpose — for instance, the setting up of a lamp for Vēṅkateśvara, instituting charities or services, offering naivedyam or making specific offerings during annual festivals, or adorning the Lord with jewels, etc. Donors, whether kings or temple officials or merchants or private devotees, presented gold and jewels and endowed lands, even entire villages, as a token of their exemplary devotion.

Kanisetti writes that, barely any of this [prasadam] was distributed freely to pilgrims, and that, [i]n some cases, donors obtained permission from the temple to sell prasadam to pilgrims for cash. This was perhaps the beginning of Tirumala’s pilgrim prasadam tradition.

In the source cited by Kanisetti, we glean that 43% villages out of 115 were indeed endowed to the temple by temple functionaries, consisting of those that recited Sanskrit and Tamizh verses, musicians, poets, dancers etc. These functionaries, upon endowing all their land and wealth to the temple, then petitioned the temple that they be allowed to split among themselves the prasādam offered to the Lord, in order to maintain themselves in lieu of their services and kaiṅkarya to the temple. They depended primarily on prasādam for their livelihood upon offering their life’s earnings and servitude to the temple. To write that donors sold prasādam for cash is a misrepresentation of the purpose, intent and the context. It is fortunate he has used the word ‘perhaps’ – there is no evidence that the prasādam tradition began here.

Coming to the most egregious and hurtful portion of Kanisetti’s article, he writes about the shrine, when it, first rose to eminence, Tirumala was an elite enterprise, explaining its focus on ritual purity; yet in the centuries that followed, its appeal has spread to many sections of society, many kinds of devotees, many cultures, many diets.

Ritual purity is an integral consideration in the preparation of prasādam in the temple kitchens of all major kṣetras of India, not just at Tirumala. It is one of the foundational practices of Hindu ritual culture and religious practice, and is not restricted to “elite enterprises”. Naivedya involves ritually purified priests offering preparations of various types as per the sectarian dietary norms. Moreover, as explained by Andrea Marion Pinkney in her paper ‘Prasāda, the Gracious Gift, in Contemporary and Classical South Asia’,

Vaishnava prasāda practices are thus highly elaborate and reflect a larger concern to care for installed deities who reside among their devotees as beloved, honored guests. Providing vegetarian food that, post-offering, is suitable for wide inter-caste distribution is an essential aspect of this care and edible, vegetarian prasāda is the norm, inflected to suit the epicurean preference of the propitiated god.

Without understanding these nuances, Kanisetti further states that, “[t]he focus on ritual purity in the supposed prasadam scam is a political gimmick, exploiting sentiments in the name of a supposed affront to the god. But Tirumala’s history is vaster than short-sighted communalism. By calling it “supposed prasadam”, and designating it as a “supposed affront” to the God, he is inadvertently (or perhaps deliberately) undermining the value of prasādam to a devotee.

Kanisetti, in stating that laddu is only a 20th century addition where poṅgal was the “original” prasāda, is wilfully making a tangential observation to ridicule and trivialize the outrage about adulteration. At Tirumala, Śrīvāri laddu is only one of the many preparations offered to Lord Vēṅkateśvara. Whether the prasādam offered in a temple changes day to day or century to century, it remains that the exact substance of prasāda is immaterial to the devotee.

Kanisetti believes Hindu beliefs and sentiments regarding the adulteration of prasādam with beef and pig fat and fish oil to be mere trifles — “melodrama” as he calls it — and attempts at stirring controversy and communal hatred. When it comes to prasādam, even the adulteration of ghee with vegetarian palm oil, soybean oil, and other inexpensive fats is unholy and exceedingly egregious to the point of fury, let alone the use of animal fat. Tirumala Tirupati Devasthanams, with all their endowments and revenue, using sub-par product that strips the sanctity of the shrine and its offering, is heartbreaking for any devotee.

References

- Pinkney, Andrea Marion. Prasāda, the gracious gift, in contemporary and classical South Asia. Journal of the American Academy of Religion 81, no. 3 (2013): 734-756.

- Nammāl̲vār. Endless Song. India: Penguin Random House India Private Limited, 2020.

- Early Inscriptions Vol I. Sadhu Subrahmanya Sastry, 2015. TTD

- Ilaṅgōv-Aḍigaḷ. The Śilappadikāram. Translated with an Introduction and Notes by V.R. Ramachandra Dikshitar, Etc. India: Madras, 1939.

- Tirumala a Study of Pilgrimage Tourism. PhD thesis by V.Thimmappa