India is a land that pays gratitude to each and every thing that* ***nurtures **well-being and prosperity. Be it the honoring of fire during a homa, praying to the sacred grooves of Banyan during Vaṭa Sāvitrī, or chanting before every meal to thank for the food that graces our plates — gratitude is at the heart of Bhāratīya traditions.

Gratitude awakens curiosity — instilling values, deepening awareness, and teaching mindful use of life’s gifts.

One Such Deśīya Tradition…

The festival of Polā is one such celebration that venerates cattle. This unique agrarian festival forms a part of the deśīya traditions, largely observed in Maharashtra and parts of Chhattisgarh and Madhya Pradesh. Farmers especially celebrate it to express reverence and gratitude to the hardworking bulls and oxen that plough their fields throughout the year, sustaining life by providing us with grains, fruits, and fresh vegetables.

Polā falls on the Piṭhorī Amāvāsyā in the Śrāvaṇa māsa. The regions of Maharashtra and Gujarat follow the Amānta calendar, in which the month ends on Amāvāsyā (new moon). This contrasts with northern India, where the Pūrṇimānta calendar is observed, ending the month on Pūrṇimā (full moon). This results in a 15-day difference in the start and end of the month. The Amāvāsyā that marks Polā also signifies the conclusion of Śrāvaṇa māsa.

Rituals for Gratitude

On this day, farmers wash their cattle thoroughly with water, milk, homemade butter, and medicated oils, and replace their ropes and reins with new ones. The bulls are then adorned with natural paints to color their horns, beautiful patterns and mandalas are drawn on their bodies, and they are draped in bright shawls, bedecked with bells and garlands. After decoration, the cattle are worshipped with haldi-kumkum and an ārati offered with a ghee lamp. They are offered traditional dishes such as Puran Polī (chapatis with ghee and jaggery filling) to eat.

This is the one day the bulls are spared from toil; they are rested, revered, and paraded in vibrant village processions. The procession begins with an elder bull carrying a wooden frame (makhar) on its horns. This bull is made to break a toraṇa, a string of mango leaves tied across posts, symbolizing strength and auspicious beginnings. All other bullocks then follow in procession. In some villages, the healthiest and most beautifully adorned bulls are rewarded.

Mārbata: The Cultural Identity of Nagpur

While the former rituals are observed in the Marathawada region, the Vidarbha region observes an additional 135-year-old tradition — the grand Mārbata procession of Nagpur.

The air resounds with chants:

ईडा पिडा घेऊन जा गे मारबत;

रोग राई घेऊन जा गे मारबत;

घेऊन जा गे मारबत !

īḍā piḍā gheūna jā ge Mārbata;

roga rāī gheūna jā ge Mārbata;

gheūna jā ge Mārbata!

Take away all the evil and go, Oh Mārbata;

Take away the diseases and miseries and go, Oh Mārbata;

Take away and go, Oh Mārbata!

The otherwise bustling lanes of old Nagpur overflow with crowds as a 10 km long procession carries two gigantic effigies — the Pīvlī (yellow) Mārbata and the Kālī (black) Mārbata. Crafted of wood, fabric, and paper, and adorned with ornaments, these effigies embody social evils, diseases, and misfortunes. The two are paraded on separate routes, meeting only at the end, where they are set aflame amidst thunderous chants — symbolizing the burning away of all negativity at the close of Śrāvaṇa māsa.

Though lacking written history, oral traditions recount that the practice began as a symbolic resistance against British rule. The Pīvlī Mārbata is said to resemble Bakabai, the Bhosale regent queen loyal to the British for safeguarding her throne. The Kālī Mārbata, on the other hand, represents the demoness Pūtanā. Over time, this custom evolved to reflect contemporary socio-political issues. For instance, during the pandemic, chants rang out:

“कोरोना घेऊन जा गे मारबत;”

Corona gheūna jā ge

“Take away Corona and go, Oh Mārbata!”

Tānahā Polā:

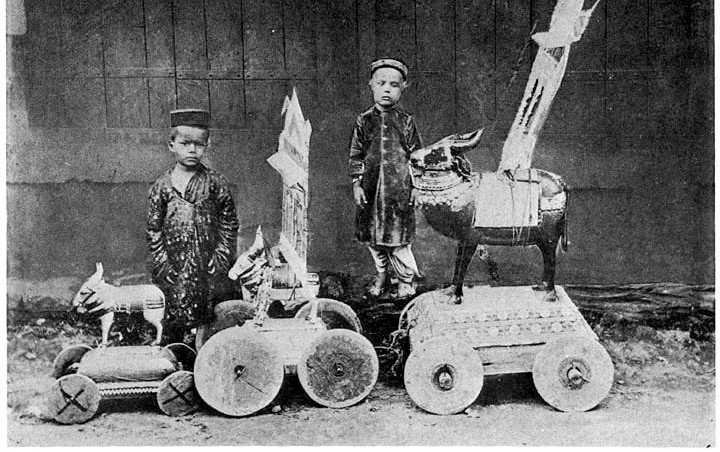

The day after the Polā (also known as Mothā Polā) on Piṭhorī Amāvāsyā is observed as Tānahā (little) Polā, again in the Vidarbha region of Maharashtra. This tradition was introduced in 1789 by King Śrīmant Raghuji Mahārāja Bhonsale II of Nagpur, who sought to instill awareness of the bull’s importance in agriculture among young cowherds.

To achieve this, he introduced decorated wooden bulls, beautifully carved from local woods such as Jaamun, Neem, and Mahua. These miniature bulls, painted in bright hues and adorned with ornaments such as necklaces, earrings, fresh flower garlands and bells, were meant to resemble their living counterparts.

Children parade these wooden bulls through the neighborhood, where people worship them and offer sweets. This allows even families without cattle to participate in the gratitude ritual. Processions are also held where children race their wooden bulls, with winners receiving rewards. These heirloom wooden bulls are cherished and passed down through generations, keeping the tradition alive.

The festival of Polā thus illustrates how rituals and traditions cultivate gratitude for cattle and agriculture, foster a sense of community, and engage all age groups — instilling values in young minds from the very beginning. It strengthens cultural foundations and ensures continuity across generations; ultimately transforming itself into the cultural identity of the otherwise orange city of Nagpur.

References

- What Is Nagpur’s Tanha Pola Festival? History, Significance & Everything You Need To Know About This Unique Festival!

- blog.mygov.in/editorial/marbat-135-year-old-nagpur-festival/

- Excerpts from the works of Historian Atharva Shivankar.

Image Sources

- Cover Image: The Bail Pola Festival Of Shravana Amavasya – Chabutra

- Image 1: Pola Festival Maharashtra | Bull Festival | Maharashtra Tourism

- Image 2: Queen Baka Bai and Marbat festival: 150-year tradition of purging evil in Nagpur - India Today

- Image 3: The Tribes and Castes of the Central Provinces of India: pt II, by Robert Vane Russell, 1916.