The mind is a curious thing. It can be bent, it can be twisted, it can even be blown away. But the moment it is directed to think in a particular angle, it rebels, making self discipline or persuasion a tricky job. Like a child in a park, it must be placated and coaxed into following the lead of the parent.

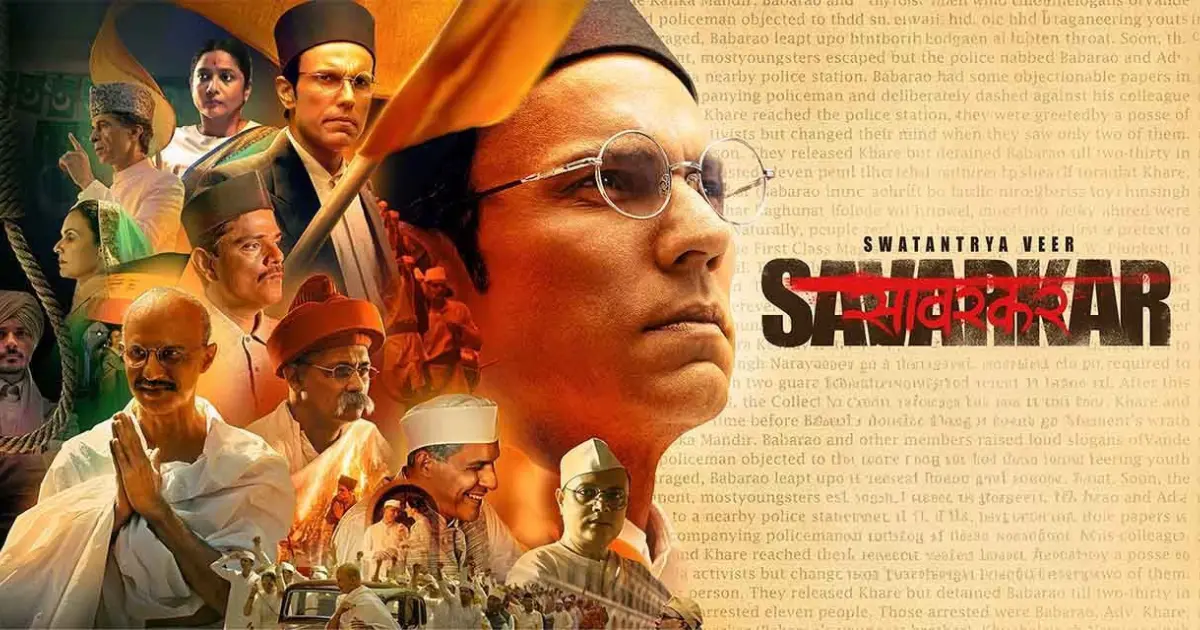

In the movie Swatantra Veer Savarkar, there is one scene which appears ordinary at the outset, but which gives a fascinating insight into the character of the man. At India House in London, Vinayak Savarkar, played by Randeep Hooda, hears the sound of partying while working. He follows it to find his peers, led by the boisterous Madanlal Dhingra, enjoying with drinks and women. They tease Savarkar for his zeal and offer him a drink.

Imagine a revolutionary, a man with a sworn purpose, chancing upon such a congregation at his residence. What is the first thought that comes to one’s mind when such a scene is depicted, what would the protagonist do? One might expect that the revolutionary would not only spurn such an offer, but scold the delinquents for forgetting their goal.

Savarkar does nothing of that sort. He smilingly acquiesces and then joins his peers in merriment, winning over Madanlal who till then considered him a prick. Fast forward a few hours and Madanlal, not finding Savarkar in the party, goes to his room and sees him furiously working on the draft of a book. It is here, in the dim light of an incandescent bulb that Savarkar convinces Madanlal that life is greater than simple pleasures of the senses.

And that his motherland needs him.

Savarkar extracts a revolutionary out of a drunk.

This is the ability of Savarkar that once earned him the distinction of being ‘one of the most dangerous men that India has produced’. The ability to be compelling. The power to persuade nearly everyone who is undecided or dithering to support his cause. Any reading of the works by the man himself, or reading the excellent biographical volumes by Vikram Sampath1, gives this impression. The movie too builds on this theme.

In the opening scenes, Savarkar explains the importance of dṛṣṭikoṇ (perception). It is a fitting context to introduce the protagonist, who is also referred to as among the first generation of Indian revolutionaries by many. It's not a matter of ‘my way or the highway’, but rather the changing of one’s perception that can alter one’s view, as he himself said.

..the real artist must not so much think for the reader as lure him into active thought; he must seek and find one fresh perception that will arouse in him all the ideas..

Will and Ariel Durant, The Story of Civilization

In all the vast corpus of works of Savarkar - be they history books, poems, plays or addresses - this power to transform is present. But from where does this śakti for transformation come?

The movie takes us to his childhood, where after witnessing the execution of the Chapekar brothers, a young Vinayak takes a saṅkalpa before his family deity, the aṣṭabhuja Mā Durgā, that he will expel the colonizers from India or die trying. Thenceforth starts a journey: of hardships, of friendships, even actual ships that crisscross the life of Savarkar. In all of these, the śakti never stops coursing through him.

And it is not just him; it is the same śakti which glints through the eyes of the eldest Savarkar, his brother Ganesh Damodar, in a much later scene, when Ganesh retorts to a sepoy who is torturing his youngest brother;

Abhi tum hum bhaiyon ko jaante nahi ho.

You don’t know us brothers well yet.

When Ganesh Savarkar passes away after a life full of devotion to the motherland, Vinayak reminisces about the saṅkalpa taken in front of Mā, and commends the dedication of his brothers and himself for never straying from the cause.

So much for Savarkar being a nāstika.

The usual suspects often deride Savarkar as someone who wrote mercy petitions to the British and professed his loyalty to them. There is a powerful scene which sets the record straight. David Barrie, the sadist jailer of Kalapani, asks Savarkar before his retirement as to why he hates the British so much? Savarkar responds that he doesn’t hate the British; he hates the colonizers and enslavers of his motherland. If the British were to cease playing that role, he would happily accord Britain the status of a friend of India.

Clear, empathetic logic, coupled with cogent articulation defines the life of Savarkar.

The movie too has its own flaws. In pursuit of creative liberty, many incorrect scenes such as the meeting of Bhagat Singh with Savarkar, and the consultation of Subhas Chandra Bose with Savarkar are shown. Though Savarkar did have an impact on these individuals, it was through his writings and not meetings. Further, even though the movie is long and feels slightly stretched in the latter half; to someone who has read the books by Vikram Sampath, it still seems woefully too short to do justice to the life of Savarkar. A full length series will be a better tribute to the life of the man.

There is again a scene in the movie where Savarkar explains who is a Hindu, and goes on to give his criteria of karma bhūmi, pitṛ bhūmi and puṇya bhūmi. But it contains a misinterpretation of Savarkar’s thoughts, where all and sundry are given the Hindu moniker under that clause.

One very good scene was Savarkar reconverting the prisoners who had been forcefully converted to Islam by the overseer at the Kalapani jail. Although not part of the movie, the exchange between Savarkar and one of the Ali brothers, where the hypocrisy of the Mohammedan is amply visible, would have made a great addition.

There is a moving portrayal of the revolutionaries who were sent to the gallows in a unique way. Against a dark background they all come to the noose with Vande Matram on their lips. These repetitive scenes are enough to send chills down the spine of the audience, and give a real glimpse into the enormity of the sacrifice of our freedom fighters. To think that the sacrifice of all such revolutionaries was usurped by a few, who dragged Bhārata further into ‘An area of darkness’ as mentioned by Naipaul, is a tragedy of epic proportions.

The movie delivers on what it sets out to do: to instill in the audience a patriotic fervor, by watching the trials and tribulations of one of the finest patriots of the 20th century. The depiction of the life of a man, who under so many restrictions could still perform such duty for the nation, is intensely inspiring. Hopefully, it will serve as a spark and a guide for whichever generation comes across this.

Resources

- Vikram Sampath’s biographical accounts on Savarkar are available at the below links.

- Padhega India

- Garuda Prakashan