ENGLISH - stress and relax!

We have all learnt this famous song.

Twinkle twinkle, little star

How I wonder what you are

Up above the world so high

Like a diamond in the sky

It is ironic to write an article on poetry as poetry is least appreciated through reading and can only be understood by hearing. It is one of those ethereal things that everyone of us intrinsically appreciates but seldom do we realize that it also has a logical structure.

There are two things that go into a poem like ‘Twinkle twinkle…’. First is the rhyme. One sees that the end of each line has the same vowels. In this article however, I am going to focus on another aspect of prosody which is the rhythm of a poem and not focus on the actual sounds. Below, I write the same poem.

Twinkle* tw*inkle, little **star

How **I* w*onder what you* are*

Up above the world so high

Like **a* d*iamond **in the* sk*y**

Denoting a stressed vowel by S and an unstressed vowel by U, we have the rhythm of the poem in every line as

S U S U S U S

We have just now explicitly realized that English poetry works based on an alternation of stressed and unstressed vowels!!

Is it true? Do we stress some vowels and do not stress other vowels when we speak English? Of course, yes! No teacher taught you in school but that is indeed the case. I will give some examples to illustrate this. Pronounce the following English words.

- Dependable

- Portable

- Icecream

- Breakfast

- Common

If you are a natively proficient English speaker, you would have stressed the vowels as follows.

- D*ependable*

- P*ortable*

- Icecr*ea*m

- Br*eakfa*st

- C*ommo*n

You might have realized this fact just now but you were doing this all the time so far while speaking English. You do not assign stresses to vowels randomly in a word but at very particular vowels. All native speakers of English stress and destress the vowels in the same way at the same places. Here are some ground rules regarding stress assignment in English.

(i) One word - One stress:

Every word has atmost one stressed vowel. If you hear two stresses, it comes from two different words. Two or more stresses cannot be in the same word. A compound word like “icecream” or “breakfast” counts as one word as they convey a single idea by being together.

(ii) First of two syllables stressed for nouns and adjectives:

If the word is a noun/adjective and has only one vowel sound, that carries the stress. If it has two vowels, the first one carries the stress. Say these sentences out loud below and observe the stress in the mentioned words.

Examples:

Pr*esent (eg. He gave me a present, focus on the present moment)

**Export (eg. The export of goods)

China* (eg. China is a nation)

T*able* (eg. The table is damaged)

Cl*ever (eg. She is clever)

Happy* (eg. She is happy)

(iii) Second of the two syllables stressed for verbs:

It turns out that if a word is a verb and has two vowels, the second syllable carries the stress. Now repeat the same activity with this other set of sentences below.

Examples:

Pr*esent (eg. They present themselves nicely)

**Export (eg. They export a lot of wool)

Begin (eg. They begin the tournament)

Deci*de (eg. They decide for us)

Observe that the stress pattern in a word changes depending on whether it is a noun-adjective or a verb as was the case with the words ‘present’ and ‘export’.

But if the verb is an imperative (giving a command), then again the first vowel is stressed.

Examples:

Pr*esent (eg. Hey you, present it!)

**Expo*rt (eg. Hey you, export it to this country!)

(iv) Single syllable auxiliaries, pronouns, articles and prepositions:

Words like ‘I’, ‘me’, ‘to’, ‘will’, ‘not’ etc… which are single vowel-ed are normally not stressed unless they are emphasized. Eg. Consider the same sentence below with the following three stress patterns.

Th*ey* g*ave me* (they gave it to MEEEE, not someone else)

Th*ey* g*ave me* (THEEEEEY gave me, not you)

Th*ey* g*ave me* (Plain usage - none of the pronouns are emphatic)

(v) Polysyllabic nouns-adjectives:

If a word has more than two vowels and is not a compound word, either the second-to-last vowel (penultimate vowel) is stressed or the third-to-last vowel is stressed (anti penultimate vowel). For a given word, this is done consistently by all speakers. Normally, words with more than two vowels end in some suffixes and there are predictable rules for stress depending on the suffixes.

When a word ends in “ic,” “sion” or “tion,” the stress is usually on the second-to-last vowel. You count syllables backwards and put a stress on the second one from the end.

Examples:

creation

commission

stenographic

When a word ends in “cy,” “ty,” “phy,” “gy” and “al,” the stress is often on the third-to-last vowel.

Examples:

democracy

photography

logical

commodity

psychology

(vi) Compound nouns:

In a compound noun made of two noun words, the second word does not carry any stress anywhere and only the first word carries the stress at the same place where it would have been, if it were to be pronounced alone.

h*o*me-delivery

(vii) Compound adjectives and verbs:

In a compound word with the second word being an adjective or a verb, the first word is devoid of any stress and the second word carries the stress at the same place where it would have been, if it were to be pronounced alone.

Examples:

old-fashioned

understand

Of course these are just general rules and there might be exceptions but the important thing is that the exceptions too are the same for all native speakers. Everyone puts the stress at the same place in a given word whether they follow the above rules or not.

So, we have now discovered (surprised that you maybe knew it already without any high school lessons) that English words carry regular stress patterns in their vowels and rhythm in English poetry is achieved by a regular alternation of stressed and unstressed vowels that convey the mood of the poem!

2. SANSKRIT & HINDI - long versus short!

Let us now move onto Sanskrit, an ancient language of the Indo-European family. One notes that in Sanskrit too, the rhythm is achieved by a regular alternation of two patterns. But it turns out that in Sanskrit, it is not stressed versus unstressed vowels that constitute its prosody.

Listen to the following Sanskrit songs to get an intuitive feel of what constitutes Sanskrit prosody. Later we will metrically analyze these songs.

Sanskrit words do not carry stresses on any particular vowel or in other words, all vowels carry equal stress in Sanskrit.

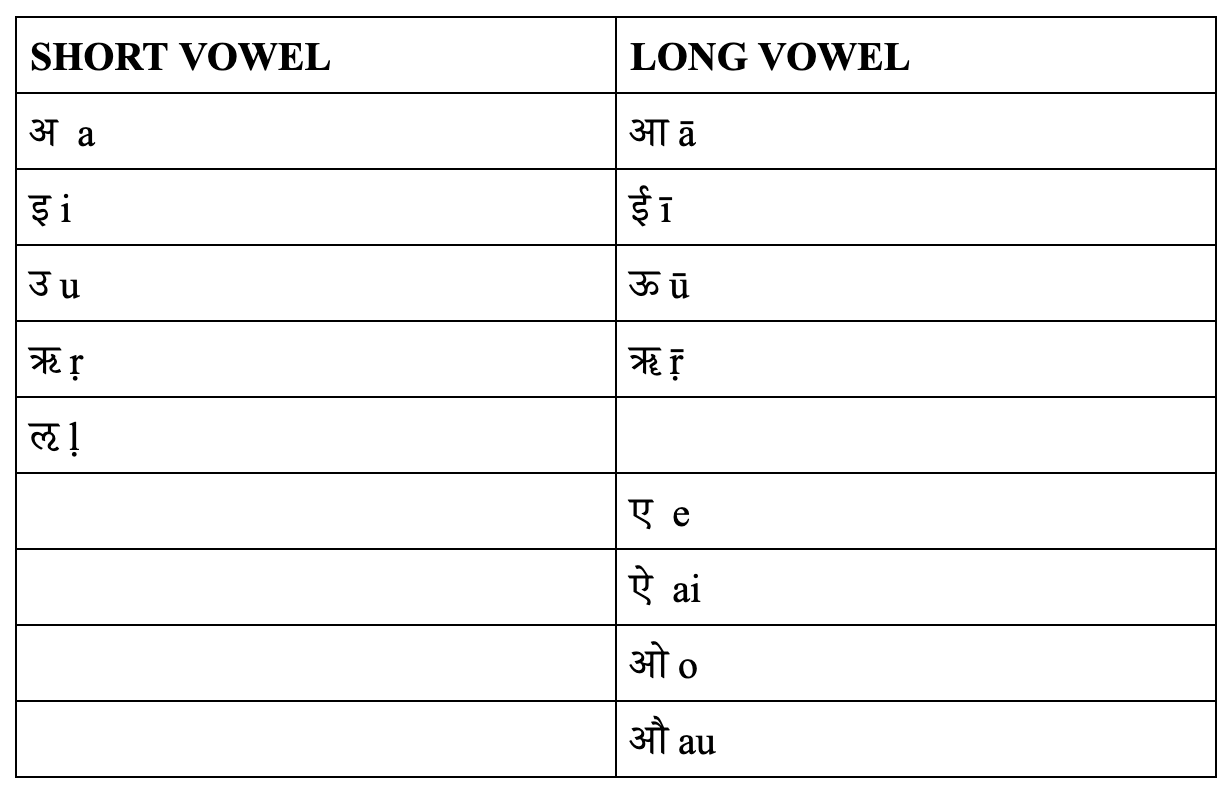

One then might think that it is the length of the vowel that matters as Sanskrit has two kinds of vowels - short and long which are mentioned below.

Note that the vowels ‘e’ and ‘o’ are always long in Sanskrit and hence a macron (line above) is not marked as it is understood that these vowels are always long. The vowels ‘ai’ and ‘au’ are long because they really are a combination of two sounds.

Even though we have short and long vowels in Sanskrit, it turns out that prosody is not achieved by simple alternation of long and short vowels. The consonants also matter unlike in English.

It turns out that Sanskrit poetry works through an alternation of what are known as long and short syllables.

We first need to master the idea of a syllable and how to syllabify a word.

A syllable is a single vowel that is optionally surrounded by consonants on either side and can be uttered as a single unit of speech.

Examples:

- e

- ai

- te

- ar

- nām

- gupt

- sprād

- srūt

- crast

A syllable can just have a single vowel (like 1,2), or a vowel with consonants only to the left (3), or a vowel with consonants only to the right (4) or a vowel with consonants on both sides (5-10). The defining feature is that it has one and only one (exactly one) vowel. The consonants to either side are optional. And the vowel may be long (like 1,2,5,7,8) or short (3,4,6,9).

It turns out that it is the syllables that play a role in Sanskrit prosody.

Now given a Sanskrit word like ‘pitaram’, how do we syllabify it? There are several ways to split this word into syllables.

- pit-ar-am

- pi-ta-ram

- pit-a-ram

- pi-tar-am

and so on…..

Which of the above syllable splitting is correct? The way to split a word into syllables is called syllabification. Let us now study the rules for syllabification which are common to all languages.

RULES FOR SYLLABIFICATION OF A VERSE:

Let us study some common rules to syllabify a word in all languages. The following are broad generic and golden rules that apply to all languages.

- Number of Syllables = Number of vowels

Since each syllable has exactly one vowel, the number of syllables must match the number of vowels. Each syllable has exactly one vowel which may or may not be surrounded by consonants to the left and right. This is however a generic rule and does not tell us which of the above four splittings of the word pitaram is correct.

- Single Consonant likes to begin rather than end

This rule says that a consonant always likes to go right and begin a syllable rather than be left and end a syllable. Consider the word pitā. It has two vowels and hence two syllables.

We can syllabify two ways as

- pi-tā

- pit-ā

- The consonant ‘p’ can be associated with only the vowel ‘i’ and can only be a part of the first syllable.

- The single consonant ‘t’ however has a choice. It can go with the first vowel and end the first syllable as ‘pit’ or it can go with the second vowel and begin the second syllable as ‘tā’.

- This rule tells us that the second of the options is correct and we must make the consonant ‘t’ begin a syllable rather than end and hence rendering the first syllabification ‘pitā’ as the correct one.

- When two consonants come together: If they can’t begin together, they split

Now consider the word parṇam in Sanskrit. We see that there are two consonants ‘rṇ’ together without any intervening vowel between them. A blind application of the previous rule that consonants don’t like to end and prefer to begin might tempt us to throw both the consonants ‘rṇ’ to the right and began the second syllable and would suggest a syllabification as ‘pa-rṇam’. This rule explains why it does not happen and one should be careful when pushing two or more consonants to the right.

Now the pair of consonants being pushed are ‘rṇ’. Now, we must really ask whether this pair of consonants can gel well together. Is there any word in Sanskrit language that begins with a consonant cluster “rṇ”? No. Which means a Sanskrit speaker is not used to pronouncing these consonant pairs together. S/he has never uttered the sequence ‘rṇ’ together as there are no words that begin with this pair of consonants. So, these consonants aren’t compatible to begin together. So, we must split them. We must make the first consonant to end and only the second consonant has the privilege to begin. Of course all consonants like to begin. But when there are two of them competing to begin the syllable and cannot begin together, the one closest to it wins. So, the correct splitting of the word ‘parṇam’ is ‘par-ṇam’ and not ‘pa-rṇam’.

- When two consonants come together:

If they can begin together - to split or not to split?

Now what if the two consonants come in the middle and are compatible to begin a syllable (as they have occurred in the beginning of words). Consider the Sanskrit word asthi. There are two ways to syllabify this word - by splitting the ‘s-th’ or not. (note that ‘th’ is a single consonant in Sanskrit and is a single sound and not a combination of two sounds as the Latin transliteration appears to suggest). So we have two options.

- as-thi

- a-sthi

We see that in this case, the consonant clusters ‘s-th’ are compatible to begin a syllable together as they occur together in the beginning of lots of Sanskrit words like ‘sthiram’, ‘sthānam’, ‘sthitam’. So what do we do with this pair in this case? To split or not to split? It is in this case that the decision to be taken is language specific. Every language has some specific pairs of consonants that are so bonded that they go together. If that is the case, then they are not split. But the thing is that, even if the consonant cluster can indeed occur at the beginnings of words, it may be that in syllabification, they prefer to split. Note that when occurring at the beginning, the pair is forced to stay together by necessity (they can’t be split!). So just because two consonants can cohabitate together in the beginnings of words (where they have to), does not mean that they will, if they are given an option to split up (in the middle of words). Of course if they have not at all cohabitated even in the beginnings of words (there are no words beginning with them), then they cannot cohabitate in the middle! That is where the previous rule applies. So, cohabitation in the beginning of a word does not guarantee cohabitation in the middle during syllabification.

The consonant pairs which go together in syllabification are language specific and have to be learnt by observing the rhythm of the language. In Sanskrit it turns out that the pair ‘s-th’ cannot go together in the middle and hence the correct syllabification is ‘as-thi’ and not the ‘a-sthi’.

There is then a possibility of three consonants together (C1-C2-C3). In this case, of course the final of the consonants (C3) always has to begin the succeeding syllable (it wins among the who gets to begin) and the initial consonant (C1) has to always end the previous syllable (more than two consonants are not compatible much in many languages and hence three consonants all cannot begin together). The question is where to put the middle consonant C2? Of course if the pair C2-C3 is compatible in the middle, then they go together but if not, it has to go somewhere. There are rules but we won’t deal with them here as they don’t matter in Sanskrit prosody.

For now, remember that consonant pairs in Sanskrit can go together only if the second member of the cluster is any of the following four consonants below.

र् r , स् s , ष् ṣ , श् ś

But if the poet decides, s/he can split the consonants even if this condition is satisfied, in order to create metrical effect (poetic license!).

Example:

The word yātrā is syllabified as yā-trā where the consonant pairs ‘t-r’ go together as the second member is r.

EXERCISE: Syllabify the Sanskrit words below

- vakṣam

- arcanā

- dharati

- mantram

- prayatnam

- karomi

- patram

EXERCISE: Syllabify the Sanskrit verses below - note that the entire verse of a Sanskrit syllable is syllabified together as though it were a single word. This is the first paragraph from a Sanskrit song called लिङ्गाष्ठकम् - liṅgāṣṭhakam. It is given in both Devanagari script and Roman transliteration.

ब्रह्ममुरारिसुरार्चितलिङ्गं

निर्मलभासितशोभितलिङ्गम् ।

जन्मजदुःखविनाशकलिङ्गं

तत् प्रणमामि सदाशिवलिङ्गम् ॥१॥brahmamurāri surārcita liṅgaṃ

nirmalabhāsita śōbhita liṅgam ।

janmaja duḥkha vināśaka liṅgaṃ

tatpraṇamāmi sadāśiva liṅgam ॥ 1 ॥

EXERCISE: syllabify the first paragraph of a poem by Śaṅkarācārya called as mātṛpañcakam. It is given in both Devanāgarī and IAST scripts.

आस्तां तावदियं प्रसूतिसमये दुर्वारशूलव्यथा

नैरुच्यं तनुशोषणं मलमयी शय्या च संवत्सरी ।

एकस्यापि न गर्भभारभरणक्लेशस्य यस्याक्षमः

दातुं निष्कृतिमुन्नतोऽपि तनयस्तस्यै जनन्यै नमः ॥ १॥āstāṃ tāvadiyaṃ prasūtisamaye durvāraśūlavyathā

nairucyaṃ tanuśoṣaṇaṃ malamayī śayyā ca saṃvatsarī |

ekasyāpi na garbhabhārabharaṇakleśasya yasyākṣamaḥ

dātuṃ niṣkṛtimunnato’pi tanayastasyai jananyai namaḥ || 1||

Now, how does Sanskrit prosody work once we have syllables? It turns out that we can classify syllables as LONG (guru) or SHORT (laghu).

Short (laghu) vs Long (guru) syllables

In Sanskrit, a syllable is defined to be long (guru) if either

(i) its vowel is a long vowel

(ii) or the vowel is followed by at least one consonant (the idea being that a consonant following a vowel sort of lengthens it by giving a gap)

If the vowel is short and not followed by any consonant and ends a syllable by itself, then the syllable is short.

It turns out that a long syllable in Sanskrit takes twice as much time to be pronounced than a short syllable (hence the name - long, short) and prosody in Sanskrit is achieved by a rhythmic alternation of long and short syllables.

Let S stand for a short syllable and L for a long syllable. Now, let us syllabify the first paragraph of mātṛpañcakam and examine the poetic genius of Sankaracarya.

Verse 1:

ās-tām tā-va-di-yam pra-sū-ti sa-ma-yē dur-vā-ra śū-lav-ya-thā

L L L S S L S L S S S L L L S L L S L

11 long and 8 short syllables in this pattern

Length of long L = twice that of short S

So total length = 11*2 + 8*1 = 30

Verse 2:

nai-ruc-yam ta-nu-śō-ṣa-nam ma-la ma-yī śay-yā ca sām-vat-sa-rī

L L L S S L S L S S S L L L S L L S L

11 long and 8 short syllables, in exactly the same pattern as the previous verse!

Length of L = twice that of short.

Total length = 11*2 + 8*1 = 30

Verse 3:

ē-kas-vā-pi na-gar-bha bhā-ra-bha-ra-na k-lē-śas-ya yas-ya k-ṣa-mā

L L L S S L S L S S S L L L S L L S L

same….

Verse 4:

dā-tum niṣ-kŕ-ti-mun-na-tō 'pi- ta-na-ya: - tas-yai-ja-nan-yai na-ma:

L L L S S L S L S S S L L L S L L S L

It is the poetic genius of Śaṅkara that he has the same pattern in a given paragraph in all his verses which give the precise rhythmic feel! This is an advanced meter which has been thoroughly mastered by Śaṅkara.

EXERCISE: Identify the patterns of the remaining stanzas of mātṛpañcakam and that of liṅgāṣṭakam.

Not all songs are written in such exact repeated patterns of long and short syllables with rigid constraints at every syllable. There are patterns with less rigid requirements. One such famous meter is called anuṣṭubh which is popularly called as śloka in common usage.

A śloka is a couplet made of four lines (each line is called a pada, or a foot, or a quarter) of eight syllables each. It has the following rules.

- It has 4 lines of 8 syllables each (four padas).

- The last syllable of a line is always scanned long (even if it ends in a short vowel, it is lengthened and scanned as long).

- The second half of odd numbered lines (last four syllables of lines 1 & 3) end in the following pattern - S L L L (S for short and L for long syllable).

- The second half of even numbered lines (last four syllables of lines 2 & 4) end in the following pattern - S L S L (S for short and L for long syllable).

- The second and third syllable of each of the four padas cannot both be short.

- The number of short and long syllables in the first half of a pada (first four syllables) is typically kept the same as that of any of the rigidly constrained last four syllables of the pada - that is, the first half (first four syllables) of a pada has at least one short syllable and at least two long syllables.

To give a flavor of this, let me represent a short syllable by da and a long syllable by dum. Then, a shloka will follow the pattern below (where the underlined portion must have at least one of the syllables long):

X X X X da dum dum dum

X X X X da dum da dum

X X X X da dum dum dum

X X X X da dum da dum

This is the most ordinary and default meter in Sanskrit that it almost feels like a prose. Most of the Bhagavad Gītā is in this meter except at dramatic moments (like viśvarūpa darśana), it shifts to more dramatic meters!

Take a famous śloka from Bhagavad Gītā with the last four syllables of each line scanned. You can see how it fits the śloka pattern.

pa-rit rā-ṇā-ya sā-dhū-nām

S L L L S L L L

vi-nā-śā-ya ca duṣ-kṛ-tām

S L L S S L S L

dhar-ma saṃ-sthā-pa-nār-thā-ya

L S L L S L L L

saṃ-bha-vā-mi yu-ge yu-ge

L S L S S L S L

There are lots of other meters in Sanskrit - if you want, study any introductory textbook in Chandas (meter).

Many languages have a prosodic meter based on syllable length. Some of them are Persian, Classical Arabic, Ancient Greek, Latin, etc. Even the poetry of modern Indo-Aryan languages work based on syllable length.

Take the example of the first four lines of Hanumān Cālisā in Hindi.

ja-ya ha-nu-mā-na jñā-na gu-na sā-ga-ra (#S=10, #L=3, Length=16)

S S S S L S L S S S L S S

ja-ya ka-pī-sa ti-hu lō-ka u-jā-ga-ra (#S=10, #L=3, Length=16)

S S S L S S S L S S L S S

rā-ma dū-ta a-tu-li-ta ba-la dhā-mā (#S=8, #L=4, Length=16)

L S L S S S S S S S L L

aṃ-ja-ni put-ra pa-va-na su-ta nā-mā (#S=8, #L=4, Length=16)

L S S L S S S S S S L L

So, here we see that the number of long and short syllables is the same in each pair of lines. And if we count short syllables as length 1 and long syllables as length 2, the total length of all lines is always 16 no matter what for all lines. Such a meter is called in Hindi as chaupai. Tulsīdās’s Rāmcaritmānas and Hanumān cālisā both are set in this chaupai meter. There are other meters too.

3. TAMIL - single versus paired!

Let us turn to another language that also is Indian but of another language family called the Dravidian family. Let us see how classical Tamil poetry works. Again the prosody works on alternation between two kinds of somethings but it is no longer stress or syllable length. Of course Tamil like any other language has syllables and the rules of syllabification are the same. Except that Tamil does not allow any pair of different hard consonants to come together and hence a consonant cluster always has to be separated while syllabifying. However in Tamil, poetry does not work based on syllable length and not on stress either. To get an intuitive feel for this, listen to the following Tamil songs.

They work on alternation between two types of entities but they are neither syllable length nor syllable stress. They are not related to single syllables. They are what Tamil grammarians call அசை asai. An asai is a fundamental unit of prosody. It is of two types and it is the alternation between these two types of asai that creates prosody in Tamil.

The two types of asai in Tamil are called as நேர் nēr *and *நிரை nirai. They do not have appropriate translations as analogs of those do not exist in any Aryan or European language. I will translate it as single and** dual**.

An asai in Tamil prosody is made of either one syllable or two syllables. If it is made of one syllable, it is called single - நேர் nēr and if it is made of two syllables, it is called dual - நிரை nirai. An asai cannot have more than two syllables in Tamil. In fact the names நேர் nēr and நிரை nirai for these single and dual asai themselves are mnemonic devices for remembering it as the word nēr has one syllable and the word nirai has two syllables. How to classify a pair of syllables as single (ner) or dual (nirai)?

The first step is to syllabify a verse before identifying the asai. The following are golden rules for characterizing single and dual asai.

- A short syllable cannot be single நேர் nēr (unless it ends a line)

- A long syllable cannot pair with anything after it to form a dual நிரை niraiasai. A long syllable always ends an asai and can never have anything after it.

(i) Single *நேர்** nēr Asai* (Patterns: L)

A single asai , as said, consists of a single syllable. But when a syllable is single and all by itself in an asai, it has to be long (we saw a short one cannot be all by itself). So, a single asai cannot be made of a short syllable in isolation. So, it has to be long.

(ii) Dual *நிரை** nirai Asai* (Patterns: SS, SL)

In a dual asai, we have two syllables. So we have the possibilities as SS, SL, LS, LL. But by golden rule 2, a long syllable cannot pair with any other syllable following it and hence this rules out LL and LS. So we only have two possibilities - SS, SL. In fact the Tamil word நிரை nirai which is the name for the dual asai itself is a mnemonic to remember the pattern and is of SL form (ai is long vowel as it is made of two sounds)

In Tamil prosody, both the single and the dual asai units of prosody are considered to be equal length unlike in Sanskrit where the long syllable is twice that of a short syllable. How do both the asai have equal length? Let us analyze.

- L (here the asai is two units long as the syllable is long)

- SS (here the asai is two units long as the two short syllables have one unit length each)

- SL (this SL pattern gains an equal length because in Tamil prosody, a short syllable is eclipsed when it is followed by a dominating long syllable.)

Note: There are many nuances in handling subtle cases like the āyudam letter ஃ, etc., which I am glossing over as this is a beginner’s level article.

NOTE:

- Unlike Sanskrit, in Tamil, there are short and long versions of the vowels e and o. So we have ē and ō for the longer versions.

- The vowels ai and au can be pronounced (and hence scanned) as short or long according to the poet’s choice.

- Tamil has a rule that no word can end with a hard consonant. So, to prevent it, it adds a little bit of the vowels u or i to serve as a bridge to go to the consonant of the next word. These are extra short. (remember Tamil does not allow two hard consonants in succession). If the next word starts with a vowel, this short u/i is removed and the end consonant is directly merged with the vowel of the next word. These are called by Tamil grammarians as குற்றியலுகரம் (kuṟṟiyalugaram) and குற்றியலிகரம் (kuṟṟiyaligaram) respectively. These vowels that serve as a bridge between the final consonant of one word and the initial consonant of the next word can be chosen to be ignored in poetry and to be treated as absent for prosodical purposes. In transliteration, I put these in subscripts to aid you in scanning (In Telugu which is another member of the Dravidian language family, this final u is no longer insignificant but very emphatic and pronounced in par with other vowels).

Interaction between lexicon and rhythm in Tamil poetry

In English and Sanskrit poetry, we have seen that each unit of repeating pattern of rhythms (like SU in twinkle twinkle , LSS in liṅgāṣṭakam) need not correspond to whole words. A single word can be split between two units of repeating prosodical rhythm. But in Tamil, it is considered inelegant to split a word so that only a part of it is in an asai. So, each pattern will constitute a word or a compound word or associated words. You will see this in scanning some Tamil poems.

Let us scan some verses from a popular Tamil song by the great 20th century freedom fighter and poet Subramania Bharati. This is the first song in the video link (I am not following the exact Romanized transliteration of Tamil as it is unintuitive in determining the pronunciation of the language for non native speakers). Following the song in the Tamil script, I will be representing them in Roman transliteration that captures the sounds of the language rather than the script.

சின்னஞ்சிறுகிளியே, கண்ணம்மா

செல்வக் களஞ்சியமே!

என்னைக் கலிதீர்த்தே உலகில்

ஏற்றம் புரிய வந்தாய்!

பிள்ளைக்கனியமுதே, -கண்ணம்மா!

பேசும் பொற்சித்திரமே!

அள்ளியணைத்திடவே-என்முன்னே

ஆடிவருந் தேனேcinnañ jiru kiliyē kannammā

selvak kalanjiyamē

ennaik kali tīrttē ulagil

ērram puriya vandāy

pillaik kani yamudē kannammā

pēsum por cittiramē

alli yanaittidavē enmunnē

āḍi varun dēnē

Let us now scan the verses of the song and organize it into asai. A nēr asai is scanned as S (single) and a nirai asai is scanned as D (double).

Paragraph 1:

cin-nan jiru -kili - yē - kan-nam-mā

S S D D S S S S

sel-vak - ka lan - jiya - mē

S S D D S

en-naik - kali - tīrt - tē - vula - gil

S S D S S D S

ēr - ram - puri -ya van - dāy

S S D D S

Paragraph 2:

pil -laik - kani - yamu - dē - kan - nam - mā

S S D D S S S S

pē - sum - po(r)* cit - tira - mē

S S D D S

al - l(i) ya - nait - tida - vē - yen - mun - nē

S D D S S S S

ā - ḍi va - run - dē - nē

S D S S S

Note that the same pattern of S and D in paragraphs 1 and 2, thereby creating a rhythmic effect - the missing ‘r’ in sanction is a poetic license to make the stanza have the same number of asai as the previous one and if you listen to this song carefully, it is very minutely pronounced. The (i) and (u) that are missed are the overshort vowels and if you listen carefully, they are barely pronounced in the song as well. As an exercise, complete the remaining stanzas and examine the patterns. There are lots of different types of meters in classical Tamil poetry based on the patterns and formulae of the arrangement of the two types of asai-s about which a Tamil grammar book will give under the side heading yāppu or yāppilakkaṇam.

4. BIBLICAL HEBREW - rhythm in meaning

From reading so far, you might think that all languages have a meter. But turns out no! Not all languages have a meter in the exact sense. The best example is Biblical Hebrew. There are intense debates on this issue (whether Biblical Hebrew poetry has meter or not). This is compounded by the fact that the Hebrew writing system does not have any alphabets for many of its vowel sounds and they have to be inferred from context. So we cannot surely know how Hebrew was exactly pronounced in Biblical times. Listen to a Bible recitation in a synagogue - you won’t feel like you can dance to it - it won’t have any beats. Surely it has rhyme (similar sounds) but it lacks rhythm (beat) which is our concern here. But what it surely has, is a unique feature, called parallelism. Parallelism is defined in the shortest possible way as “rhythm in meaning”. That is, the sounds need not have rhythm but the meanings kind of rhyme. Since it is the meanings that matter for parallelism, Biblical Hebrew parallelism can be fully appreciated through a translation. (Thank goodness, you won’t see any strange Hebrew verses in this section - only English translations!)

For example, read this poem called “The Song of the Sea”, one of the oldest songs in the Bible. It is sung by Mariam (after whom Mary is named), the sister of Moses, after God delivers the Israelites from slavery in Egypt by parting the sea so that the Israelites can escape, and drowning the Pharaoh and his army when they follow through. (Ref: Exodus Chapter 15)

The Lord is my strength and my defense;

he has become my salvation.

He is my God, and I will praise him,

my father’s God, and I will exalt him.

The Lord is a warrior;

The Lord is his name.

Pharaoh’s chariots and his army he has hurled into the sea.

The best of Pharaoh’s officers are drowned in the Red Sea.

The deep waters have covered them;

They sank to the depths like a stone.

Your right hand, Lord, was majestic in power.

Your right hand, Lord, shattered the enemy.

In the greatness of your majesty

you threw down those who opposed you.

You unleashed your burning anger; it consumed them like stubble.

By the blast of your nostrils, the waters piled up.

The surging waters stood up like a wall;

the deep waters congealed in the heart of the sea.

This is what I meant when I said “Biblical Hebrew poetry has a metric in meaning and not in sound”! There are a lot of other patterns possible as well. You may just look up different types of parallelisms in Biblical Hebrew.

I hope from now on, you will be able to appreciate poetry in these languages with a more nuanced ear and also analyze the prosodical system in your own native language if it is not covered here.