Meaning Making in Culture

Of all the functions that Culture provides us, one of the greatest is the meaning making process. Man’s quest for meaning in life is eternal and it has been the primary function of Culture to provide meaning in individual and social life. All tradition and dharma affirms that life is not random; it has meaning. That something exists instead of nothing; that there is a cosmos, intelligent life, and a species capable of reflecting upon its own existence, is not a random occurrence.

From a traditional point of view, a Culture cannot call itself so unless it comes with an elevating meaning-making process. Anarchy and nihilism do not create and cannot be a part of culture. They are essentially de-culturing techniques

Where does the meaning-making process derive its authority from? It comes from a view which considers consciousness primary and matter emergent. It says that matter is emergent and a function of the will of supreme consciousness. Hindu darśana speaks very clearly on this. Whether it is Sāṅkhya or Kaśmīra Śaivism, they speak on how supreme consciousness is behind the creation of universe and everything and being in it.

Kaśmīra Śaivism clearly says that, vimarśa, where Śiva reflects upon himself in his own light, is his fundamental and inalienable nature. And since it is a non-dual system it also says that we all are actually Śiva who have forgotten their true non-dual nature and hence have come to identify as different individuals. And it is the purpose of life to realize one’s true essence, which is Śiva himself. Different systems like Vedānta also speak the same thing in different terminology.

The quest for meaning, thus, is the fundamental human urge. The tendency to reflect upon the deepest mysteries of the universe and life is almost reflexive to human nature and that is because it is reminiscent of the nature of the supreme consciousness. Vimarśa is fundamental and innate to all of us. We are meant to search for meaning in life.

This is where the meaning-making process in a traditional society receives its authority from.

Not everyone though is meant to search for ultimate meaning. That is for one in a million from one life perspective. But just like the nature of Śiva is reflected in all of us, because we all come from him, the tendency to search for meaning reflects in all human endeavors, and not just in the search for ultimate truth. The incomprehensibility of life is woven in meaningful stories reflecting higher elevating truths. In a culture where the meaning-making process is in place, like Sanātana Dharma, nothing happens without a reason. Nothing is a mere accident. Everything makes sense and connects to everything else, in great arcs of meaning. These arcs cover our lives completely, making life comprehensible and graspable. They give our lives the much needed context.

The micro of our actions connects immediately to the macro of the cosmic rhythms. The rains are good in a particular year because the yajña was performed properly. The household runs well because the family follows the rituals. The husband has a long life because the wife follows all the vratas. The daughter-in-law cannot conceive because the neighbor has done some magic on her. People suffer because they have done something bad in previous lives. Some live a grand life without doing much to earn because they had earned it in the previous life, or they are going to pay for it in the next one.

Meaning infuses all life: right from birth. It is derived from the identities that an individual has in a society. Identity for a traditional man is not exclusive. There are multiple layers to it. One is a Bhāratīya, Hindu, Vaiśya, Telugu, male, elder son in a family. Each of these identities has some importance and pride attached to it. Each identity is associated with a set of responsibilities. The purpose of life is to fulfill all these responsibilities. Every man is born with a list of ṛṇas in his life. To repay those ṛṇas is dharma.

In a traditional society one’s job is also not simply to earn livelihood. It is also in line of repaying the ṛṇas. That is why even doing your job gives meaning in life

Birth, death, life, dharma, art, everything is full of meaning. But before we come to the role of art in the meaning-making process it is necessary to investigate whether the meaning-making process in itself is just necessary or also a sufficient condition.

The Anchor of Dharma

The meaning-making process is a necessary but not a sufficient condition. A lot of crazy cults are meaningful to their followers and yet they are at the end of the day – crazy cults and nothing more. Communism ‘made sense’ to a lot of people who saw it with a hope that it would relieve them from the miserable existence that a materialistic life threw them into. Fundamentalist religious cults associated with historical Abrahamic religions also tend to give great meanings to their adherents. The inquisitors who burned ‘heathens’ and ‘witches’ to death also had a certain meaning in life. Such meaning is not only not sufficient, but inherently dangerous.

What makes the meaning-making process sufficient is the fact that it is always tied to a higher goal and a greater meaning. Every meaning leads to a higher meaning with the series continuing on an ever-increasing gradient, ultimately culminating in the realization of the Ultimate Truth, which is the highest goal of the meaning-making process.

In Sanātana ethos the ultimate goal is always mokṣa. This does not mean that everyone is supposed to or expected to get mokṣa in this life, but it is the ultimate tether of every darśana, every institution, and every meaning making process. The direction of everything is oriented towards mokṣa irrespective of the intervening steps.

The tether of mokṣa prevents the degeneration of the meaning-making process into internally consistent but ultimately false cults. This is the universal, the mārgīya element of the process. When the ultimate principle is mokṣa, the path never wavers too far from the goal. While Mārga provides the principle, Deśa provides the material propos. The deśīya element takes care that the saṃsāra doesn’t get lost or the quest doesn’t become insipid in the pursuit of mokṣa. It makes sure that the meaning also makes our lives beautiful and enjoyable. And art is the vāhana, the vehicle of the deśīya element. Art is how we see meaning even in the banal and the mundane and art is how we see beauty.

Art as a Meaning Making Process

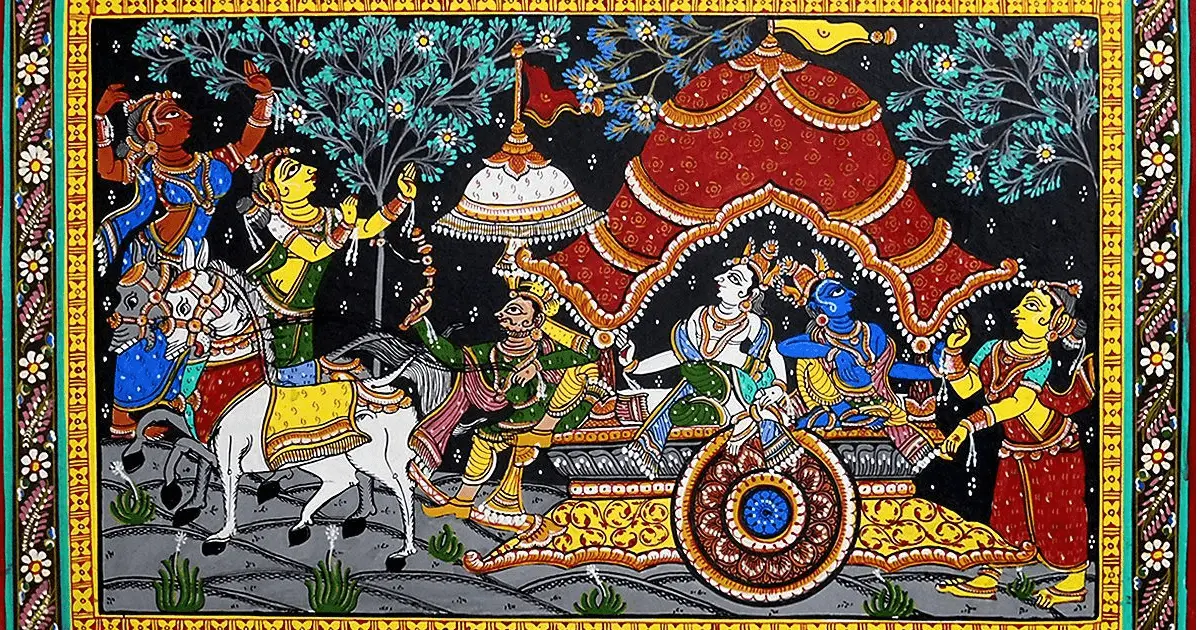

Art is something which lends naturally to this process. Through symbols, metaphors, idioms and anecdotes, the ordinary is rendered extra-ordinary, bearing great meaning. Great truths, secrets and mysteries of life are made accessible by great seers and artists by reflecting them in the world around us. Bearing the aspect of the divine, something more than its material aspects suggest, everything becomes elevated and meaningful. As the Dasarūpa states:

The work of art can only nourish the spectator, he can only have delight in it, when he is not cut off from its meaning.

(COOMARASWAY 85)

Hindu art is: that which is beautiful; that which is meaningful; and that which elevates our consciousness. What is beautiful is also meaningful and also truthful. They all go together. The Hindu tradition provided art as a means to transcend the limitations of daily life. Art not just provided a happy respite from the drudgery of daily life, but also elevated the aesthete or the enjoyer of art to a higher plane of consciousness, thereby enriching his life in more than one way.

Art had to be beautiful. The merely strange had no currency in the Hindu ethos. The Hindu artist was not allowed to wallow in misery. Dwelling of pain had to be cathartic for it to be called art. He was also not allowed to create something not beautiful. Art couldn’t be just strange. Strange was not equal to beautiful. But at the same time he did not stop at beautiful. Beauty had to be infused with great meanings of life, existence and cosmos. And this meaning had to be consciousness elevating.

It was art which negotiated the mundane and the universal; the sāṃsārika and the divine. Art, seen like this, is the great meaning-making process. It makes our existence meaningful and beautiful and simultaneously nudges us towards the ultimate goal of mokṣa. It is this meaning-making process that we have lost today, in our pursuit of a materially prosperous life. The tragedy of a modern life is that meaning becomes increasingly elusive when cultural identity markers collapse one after another. Modernity decimates every single traditional identity including religion, nation, tradition, community, family, gender etc. and seeks for a universalized and atomized individual. And as all these markers collapse, as these identities disappear one after another, so does the meaning making process and without it life becomes aptly meaningless.

We have exchanged meaning for an ever elusive logic. Logic is incapable of explaining life’s deepest mysteries to us and that would have been alright had the modern-rational complex not been claiming universality and exclusivity. But what falls outside the purview of logic and rationality is often considered non-existent or invalid.

And as this urge to see life from only one prism of logic sets in, all that is beautiful with life starts disappearing. The beautiful arcs of meaning around us collapse and a deep civilizational dejection sets in the absence of meaning. The collapse of culture around us is accompanied with the collapse of meaning. As Loren Eiseley wrote:

“Man’s second rock of certitude, his cultural world, that had gotten him out of bed in the morning for many thousand years, that had taught him manners, how to love, and to see beauty, and how, when the time came, to die – this cultural world was now dissolving even as it grew. The roar of jet aircraft, the ugly ostentation of badly designed automobiles, the clatter of the supermarkets could not lend stability nor reality to the world we face.”

(EISELEY 129)

In a world where all traditional identities collapse and an individual truly becomes an individual, the meaning-making process in our life disappears and a great darkness sets in. In such a world, art, arising out of Hindu culture and advised by Sanātana dharma is still capable of lending a helping hand to the individual, to bring his life in order, to give meaning to it and elevate it to a greater understanding and deeper wisdom. Art is more capable than others because it is as available to the contemporary individual as it is to a traditional family, at least in many of its plastic forms.

While the family around us collapses, the customs and rituals go out of fashion, Hindu art, architecture, sculpture and painting still exist, still conveying the same meaning to us as they were a thousand years ago. While our grandmothers capable of telling us great and meaningful stories are no longer there in our homes to continue the grand tradition, the legends of Rāma and Kṛṣṇa are still available to all of us to help us out of our dilemmas and our depression.

As the great guilds of artists collapse, the individual painter can still get inspired by the murals on our temple walls and recreate scenes from our epics and Purāṇas, which are still meaningful to us in our individual lives. While we see a lack of order in our lives and a lack of the ‘sense of sacred’ in the State, politics and society, an ancient temple with its ancient ritual is not that far for most of us to give us a sense of order, sacredness and meaning in life.

There is a reason that as a culture we were more interested in ‘what happens’ than ‘what happened’. ‘What happened’ becomes dated. ‘What happened’ is limited. While ‘what happens’ is timeless and limitless. The great seers of this great land observed the world from a śuddha citta and created analogies capable of reflecting the timeless and divine principles and messages which are still relevant to us. And they did this through poetry, literature and art.

Those symbols, metaphors and analogies are bridges to the divine and art is the process which can still help individuals to recreate a world full of meaning and satisfaction; which can help them out of moral and ethical dilemmas of life; which can help them overcome meaningless and aimlessness. Art is the redemptive force of culture

Endnotes

- Eiseley, Loren. The Firmament of Time. Bison Books, 1999.

- R. Lipsey, (ed.), Coomaraswamy. Selected Papers, Volume 1. Princeton University Press, 1977.