The legend of Samudra Manthana (churning of the ocean) offers interesting metaphors for modern notions of sustainability and technology, and some new ways in which to think about them. It represents an early attempt in ancient India towards co-operation, resource utilization, and sustainable usage. After several major wars between themselves, the Ādityas and Daityas come to the negotiating table to harness the earth’s resources together, and more critically, they do so under the guidance of their spiritual preceptors. Let us visit the tale now-

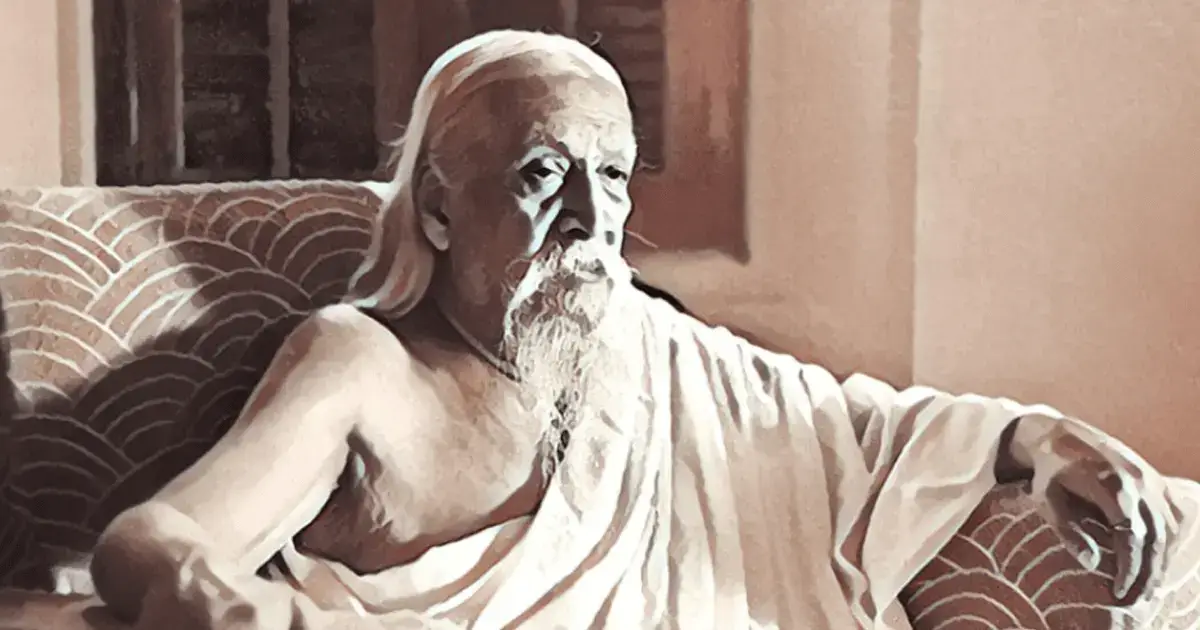

Born in the glorious lineage of Bhṛgu, Śukrācārya is the guru to Daityas (or Asuras), and possesses the knowledge of immortality - Mṛta Sanjīvanī Vidyā. This allows him to revive Daityas after death, thus ensuring a constant supply of warriors in the never-ending battles against Ādityas. Descended in the equally legendary line of Aṅgiras, Bṛhaspati is preceptor to the Ādityas, who at this time are severely weakened due to a curse by ṛṣi Durvāsā that renders them powerless against the Daityas.

After generations of war, guided by their gurus, the Ādityas and Daityas come together to churn the ocean and produce true immortality - beyond physical death - or amṛta, among other resources. The difference between Śukra’s mṛta sanjīvanī vidyā and the amṛta that will be produced represents an essential duality: Śukra has “technological” knowledge, i.e., knowledge of material productions that could enhance life capabilities in the physical world. But it is also quintessentially ‘āsurika,’ i.e., it blinds those in possession of it to the more real truths and technologies possible (genuine amṛta). Arriving at that truth will require something more than Śukra’s innovation, technological ability, and material knowledge. It will require an ethical base, a consciousness for dharma, a ‘checking’ mechanism - which is provided by Bṛhaspati.

And thus we receive a frame for thinking about technology and sustainability in a dhārmika context. Śukrācārya represents technology - innovative, forward-pushing, intelligent; while Bṛhaspati represents sustainability - restrained, deliberate, thoughtful.

We will revisit this frame after a brief detour into Saṃskṛta roots, and how they shape our thinking about these concepts.

Our Words for Technology

At the root of most Saṃskṛta words for things such as technology, mechanics, and engineering sits the word ‘yantra,’ as found in terms such as yāntriki, yantra-tantra, yantra-vidyā, yantra-jñāna, and more. In the Apte dictionary, ‘yantra’ is defined as ‘that which restrains or fastens, any prop or support.’ The etymology given is of यन्त्र्-अच्, deriving the word from the dhātu √yantr. In the Dhātupāṭha, Śrī Pāṇini defines √yantr as ‘restraining, curbing, checking’ or ‘saṅkocana.’ A further connection can be made with the dhātu √yam, which means ‘checking, curbing, restraining, moving around’ - apariveṣaṇe, uparame, pariveṣaṇe. Most literally then, ‘yantra’ translates to ‘an instrument of curbing and restraint.’

This reveals to us a key insight in how Indian thought approaches technology. A yantra in the Indian context is encoded with the evocation of hesitation and restraint. This scales to all words formed from it, including the words for technology listed at the beginning of this section. Contrast this with the current model extant across the globe - move fast and break things, disruptive innovation, accelerationism, and values-agnosticism.

Our Words for Sustainability

When it comes to sustainability, Saṃskṛta equivalents are identifiable based on what aspect of sustainability we wish to evoke. Words such as ‘saṁrakṣaṇa’ highlight the aspect of conservation or preservation, while ‘sthiratā’ evokes stability. There are also words such as ‘samañjasatā,’ ‘yuktajīvanam,’ and ‘dhruvatā’ which evoke balance and stability. But the words that seem to capture the whole of sustainability are ‘dhāraṇīyatā’ and ‘dhāryatā,’ both of which stem from the root √dhṛ, which means ‘holding, being, supporting’ or ‘avasthāne’ and ‘avadhvaṃsane.’ The same root also gives to us the very name for Indic thought and tradition - dharma (धृ-मन्).

Dharma encompasses the notions of tradition, rule, order, and stability. It is both that which upholds and that which is to be upheld. Put simply, the pursuit of dhārmikatā is by definition a pursuit of sustainability. By seeking natural harmony and consonance with reality (ṛta), dharma is a system inherently designed to be sustainable. If something is dhārmika, it automatically contains the values of dhāraṇīyatā and dhāryatā. It automatically ensures an eye for balance, conservation, preservation, and stability. Conversely, any system tuned for dhāraṇīyatā and dhāryatā automatically tends towards being dhārmika.

In other words, dharma IS sustainability, and sustainability IS dharma.

With these notions for technology and sustainability established, we may visit the Churning of the Ocean in a new light.

Samudra Manthana as a Technological Allegory

Material technology has limited scope, and it naturally tends towards excess, disharmony, and greed. Left unchecked with the Asuras, the mṛta sañjīvanī vidyā becomes dangerous technology - instrumental in the spread of adharma over dharma. Or given our current frame, the spread of disruptive accelerationism over sustainability and restrained usage.

The very act of churning, and the collaboration between two opposing forces (Daityas and Ādityas), symbolizes a necessary duality of innovation with ethical oversight. It suggests a paradigm for conscious innovation over disruptive, and deliberated development over accelerationism. That the churning rod, Mount Mandara, has to be stabilized on the back of Viṣṇu himself (in the avatāra of Kurma), tells us that technological progress must rest on the solid foundation of sustainability (symbolized by the stability and support provided by Kurma). Without such balance, we will be led to chaos rather than prosperity.

Equally symbolic is the emergence first of halāhala, or poison. All human creation is double-edged, it can both create and cleave. Externalities and collaterals are to be managed, not dismissed away at the altar of moving fast and breaking things. If not checked, technological output can turn into poison, destroying the entire world. This is a stark warning against unrestrained technological development and a reminder of its unintended consequences. And what does it take to mitigate against this? Śiva himself, embodying the principle of utter austerity and yogic self-application. Sustainability requires a self-fulfilled restraint, which may often be sacrificial in nature.

Emerges from the churning Airāvata, taken by Indra. Emerges Ucchaiśravas, taken by Bali. Emerge Lakṣmī and Kāmadhenu, wealth and prosperity - shared among the collaborators. And then emerges amṛta proper, and given that technology is a double-edged sword - it may only be wielded by those capable of swinging it right. Thus does Mohinī afford it to the Ādityas, who under Bṛhaspati’s guidance can be trusted to use it correctly. In other words-

Technology must ultimately serve ethical purposes, and be wielded by those who are aligned to dhārmika values.

We are thus served the following lessons on technology and sustainability through using the Samudra Manthana as a telling allegory:

Collaboration is Essential

Progress requires cooperation across diverse perspectives, including opposing ones. This mirrors the Ādityas and Daityas working together despite their differences. In the modern world, all forms of technology are heavily centralized. Oligarchic corporations and individuals own the platforms that seemingly guarantee our freedoms of speech and ability to communicate with each other. Far from a decentralized, collaborative technological society, we accelerate towards a brave new world that weaponizes our attentions against us.

Ethics Must Guide Innovation

Like Bṛhaspati’s oversight of the process, modern technological advancements need ethical frameworks to ensure they align with sustainability and the greater good. This is in direct contrast to the modern ‘values-agnostic nihilism’ prevalent in design and creatorship. When we move fast and break things, when we make a virtue out of disruption, we make the cardinal error of thinking that progress is a scaling problem. In reality, all of civilization is a sustaining problem, not a scaling problem. Left on its own, technology is inherently āsurika. It channels intellect, desire, and ambition towards actions that are ultimately adhārmika and unsustainable. To bring dhāryatā into our yāntrikī, we need the ethics of dharma.

Modern discourses around sustainability often emphasize technical fixes—renewable energy, circular economies, or carbon capture technologies. While these are vital, the dhārmika perspective reminds us that sustainability is not just about external solutions but also about internal alignment with dharma. It is about cultivating a consciousness that harmonizes human ambition with the rhythms of nature.

To be clear, this is not a luddite vision that calls for us to return to the caves and fire-lanterns. It is not a rejection of innovation but a call to reshape it towards a more conscious, deliberate, and ethical husbandry. It aligns with principles of ṛta, recognizing that the natural world is not a resource to be exploited but a system to be harmonized with. And the duality is inherent - one cannot exist without the other. We need the Śukra dimension to drive innovation, technological creativity, and material progress. We need the Bṛhaspati dimension to hold this on a foundation of ethics, restraint, and deliberation. And the two are to be yoked together, or united, by an ultimate dhārmika paradigm that both acknowledges the divine hand (the base of Kurmāvatāra), and surrenders to the self-sacrificing Puruṣa (the drinking of halāhala by Śiva).