National Commemorative Seminar on 60 Years of Pandit Deendayal Upadhyaya’s Integral Humanism Lectures

Our report on a seminar held to mark the 60th anniversary of Pandit Deendayal Upadhyaya's seminal lecture series on Integral Humanism, held at NDMC Convention Center, New Delhi.

Share this Page

Organized at: NDMC Convention Center, New Delhi | Date: 31 May 2025

Day 1

To mark the 60th anniversary of Pandit Deendayal Upadhyaya’s seminal lecture series on Integral Humanism delivered in April 1965 in Mumbai, a National Commemorative Seminar was organized at NDMC Convention Center, New Delhi, under the aegis of Dr. Shyama Prasad Mookerjee Research Foundation in collaboration with Public Policy Research Center, Ektam Manavdarshan Research and Development Foundation, and Prabhat Prakashan — uniting thought leaders, scholars, and policymakers in a shared pursuit of intellectual and national advancement. The seminar brought together eminent thought leaders, policymakers, ideologues, and scholars to reflect upon the enduring relevance of Panditji’s vision for Bharat’s civilizational resurgence.

The Day 1 session unfolded with insightful addresses from five distinguished speakers in the following order: Shri Arun Kumar, Shri Shivprakash, Dr. Mahesh Chandra Sharma, Shri Shankarananda, and Smt. Nirmala Sitharaman. The cumulative impact of their speeches presented a deep, multi-dimensional interpretation of Deendayalji’s thoughts across political, social, economic, and spiritual planes.

Shri Arun Kumar – Opening Address: Ideology Rooted in Dharma and Nationhood - Sah Sarkaryawah, Rashtriya Swayamsewak Sangh

Shri Arun Kumar began the seminar by emphasizing that Pandit Deendayal Upadhyaya’s thoughts are neither imported nor derivative. His philosophy, he stated, emerges from the civilizational wellspring of Bharat and reflects a worldview where Dharma, not materialism, is the central organizing principle.

He contextualized this within the shifting landscape of India’s freedom struggle, observing that post-1911, the national movement increasingly narrowed its focus to mere political independence (Swarajya), often at the cost of the more comprehensive vision rooted in ‘Sw’ — Swarajya, Swadeshi, and Swadharma. In this atmosphere of ideological drift, Dr. Syama Prasad Mookerjee and Pandit Deendayal Upadhyaya set out to revive a civilizationally anchored discourse through political action.

Shri Arun Kumar highlighted two core questions that Deendayalji took upon himself to answer: Do we have an original worldview rooted in our ethos? And, how can such a worldview be made acceptable within the modern democratic framework?

These were not abstract concerns, but deeply pragmatic inquiries that shaped Deendayalji’s organizational and philosophical contributions.

In response to these, Deendayalji laid the foundation of a pan-national organization and in 1965, articulated his philosophy of Ekatma Manav Darshan (Integral Humanism). This was not a novel doctrine, he said, but a timely commentary rooted in India’s timeless tradition—akin to how Shankaracharya, Swami Vivekananda, Lokmanya Tilak, and Mahatma Gandhi had interpreted the Gita for their times.

भारतीय चिंतन यह मानता है कि सब कुछ ईश्वरमय है — ईशावास्यमिदं सर्वम्। प्रकृति, चेतन-जड़, सभी में एक ही तत्व है। सब एकदूसरे से जुड़े हैं — वसुधैव कुटुम्बकम्।

This foundational unity, Shri Arun Kumar emphasized, is at the heart of Deendayal Ji philosophical and political vision.

Drawing attention to how the West separates the individual from society and the material from the spiritual, Shri Arun Kumar reminded the audience that “भारतीय संस्कृति में व्यक्ति समाज का अंग है, उपभोग की वस्तु नहीं।” He clarified that Deendayalji’s Integral Humanism (एकात्म मानव दर्शन) is not merely a political ideology but a darshan — a worldview grounded in the indivisibility of the body, mind, intellect, and soul.

He noted how the Western dichotomy of capitalism and communism both fail to address the core of human needs. One overemphasizes individual desire; the other is state control. In contrast, Integral Humanism places the individual in a harmonious relationship with society, nature, and the divine.

Session 1 - Pandit Deendayal Upadhyaya Man and the Idea - Shri Shivprakash, National Joint Secretary (Organisation) BJP

Shri Shivprakash delivered a powerful oration tracing how Deendayalji rescued the very idea of Bharat from being rendered an “अविषय” (non-issue) in post-independence political discourse. He argued that after 1947, those in power deliberately omitted questions about Akhand Bharat, Partition, and cultural integrity. Deendayalji, as a thinker and organizer, challenged this silence by building a strong ideological and organizational framework rooted in authenticity, simplicity, and spiritual resolve.

He traced how by 1967, under Deendayalji’s stewardship, the Bharatiya Jana Sangh had grown into a significant political force — with 35 Members of Parliament, nearly 9% vote share, and participation in several state governments. In Uttar Pradesh, Madhya Pradesh, and Rajasthan, it had become the second-largest party. This, he stressed, was possible not by political maneuvering alone, but by the exemplary character and conviction of Deendayalji himself.

He outlined the many dimensions of Deendayalji’s persona: a brilliant scholar, deeply sensitive to the plight of the poor, disciplined, honest, and profoundly self-effacing. Despite personal hardships — losing his parents and brother early in life — he excelled academically, even qualifying for the ICS, which he declined to pursue a life of national service.

As a swayamsevak from 1937 and a pracharak from 1942, he devoted himself to nation-building. From 1952, he served as General Secretary of Jana Sangh for 15 years, and in 1967 became its President — though fate permitted only 42 days in that role before his mysterious and untimely death.

Shri Shivprakash shared many inspiring anecdotes — from his choosing a roadside barber in Lucknow to help someone earn a living, to his insistence on paying the fare difference when mistakenly boarding a higher-class train compartment. He cited Rajmata Scindia’s admiration for Deendayalji’s simplicity — walking with his own bag, resting on a towel spread on the stage, unbothered by position or prestige.

He also spoke of Panditji’s sharp intellect and biting wit, as expressed in his editorship of Panchjanya, Rashtradharma, and Swadesh — publications through which he expressed his original views on economics, culture, and politics. His Diwali editorial “लेखाजोखा” assessed post-Independence India’s gains and losses with satirical precision.

Spiritually profound, he interpreted the Vedic invocation “शतं समाः जीवेम” not merely as long life, but as a call for ensuring livelihood and dignity — linking spiritual ideas with policy imagination. He gave fresh meaning to national symbols: seeing Rama’s restraint as Himalayan, and Lakshmi’s seat on the lotus as rooted in sea-trade prosperity.

At the core of Deendayalji’s life was integrity — unity in “मन, वचन और कर्म” (thought, word, and deed). He shunned the word “I” in his writings, always preferring “we,” reminding us that in nation-building, the individual ego must dissolve. As he put it, “Not I, but We.”

Even after reaching national stature, he once burned his educational certificates, declaring, “These certificates no longer hold relevance — I now dedicate myself wholly to the nation.” When urged by his maternal uncle to return home for family responsibilities, he wrote back, “National service comes first — I cannot abandon my work with the Sangh.”

His passing drew condolences from across the political spectrum — from the President, Prime Minister, and opposition leaders — a tribute to his ‘अजातशत्रु’ (one without enemies) personality.

In closing, Shri Shivprakash remarked: “Deendayalji’s thought, action, and conduct were integrally one. To truly understand his philosophy, we must embody his life. Not just theory, but emulation — only then can we fulfill his vision of Antyodaya.”

Highlighting his organizational genius, Shri Shivprakash elaborated on how Deendayalji transformed Jana Sangh from a marginal political group into a pan-Indian force. His speeches, particularly his mahamantri prativedan (General Secretary’s reports), were not administrative notes but ideological manifestos.

In conclusion, Shri Shivprakash asserted, “Panditji did not merely build an organization; he infused it with a soul.”

Dr. Mahesh Chandra Sharma - President Integral Humanism Research & Development

Dr. Mahesh Chandra Sharma offered a scholarly exposition of Integral Humanism, focusing on its philosophical structure and historical context. He emphasized that the doctrine arose not from reaction but realization — a native model rooted in Bharatiya metaphysics and social life.

He clarified that एकात्मता is not uniformity but unity. The concept holds that society, the individual, and the cosmos are interrelated through Dharma. He also highlighted Panditji’s critique of Western materialist frameworks, citing his rejection of both capitalist excess and communist totalitarianism.

Citing from the original Mumbai lectures, he explained how Panditji viewed the individual as a fourfold being — शरीर, मन, बुद ् धि, और आत ् मा. Any economic or political model that fails to recognize this holistic structure would inevitably lead to exploitation or alienation.

He recalled Deendayalji’s early intellectual works—his biographies of Chandragupta Maurya and Adi Shankaracharya—which symbolized the twin ideals of political and spiritual unity of Bharat. Later, his polemical essays like “अखंड भारत क्यों?” and “हमारा कश्मीर” reclaimed these forgotten concerns and re-established them at the national level.

Dr. Sharma noted how this vision directly informed Deendayalji’s advocacy for decentralization, self-reliant villages, and ethics in economics. He recalled how in 1964 at Gwalior, Deendayalji presented a draft of Integral Humanism to a cadre of karyakartas — one side of the document outlined principles, while the opposite pages were left blank for suggestions. This collaborative exercise led to the formulation of a final doctrine encompassing both siddhānt (principle) and nīti (policy).

In 1965, at the Bengaluru convention, this framework was officially adopted as the ideological compass of the party, and the speeches in Mumbai became its foundational articulation — now completing 60 years. Dr. Sharma emphasized that this milestone should be seen as a moment of आत्म-चिंतन (self-reflection), not आत्म-श्लाघा (self-congratulation).

He cited Panditji own words-

राज नहीं, समाज बदलना है। समाज बदलने की राह में जो रोड़ा हो, वह राज बदलना है।

Real transformation, he insisted, lies in reforming public consciousness. Panditji warned against shallow electoral habits-

सिद्धांतहीन मतदान ही सिद्धांतहीन राजनीति को जन्म देता है।

His enduring appeal was, “Empower the voter. As long as the voter remains indifferent or uninformed, democracy will continue to be fragile — regardless of who holds power.”

Dr. Sharma underlined that Integral Humanism must be studied not as nostalgic idealism but as a practical philosophy for the future — one that equips India to shape her destiny through culturally anchored and ethically robust democratic means.

Session 2 - Work, Wealth, and Wellbeing: Towards People- First Economy - Shri Shankarananda, National Organisation Secretary Bharatiya Shikshan Mandal

Shri Shankarananda brought a contemporary academic perspective to the discussion, illustrating how Integral Humanism can serve as an alternative economic model for the 21st century. He explored Deendayalji’s conception of enterprise and production, emphasizing self-employment and the decentralization of industry as foundational elements. He argued that Deendayalji’s economics is not a study of wealth alone, but of life itself — a holistic discipline guided by Dharma.

He noted that the current era marks a transition — a ‘sankraman kaal’ — where India is redefining itself not only administratively but civilizationally. Since 2014, India has begun to turn inward, seeking the ‘soul of India’ in its idiom. We are witnessing a shift from ‘India’ to ‘Bharat’, from policy informed by Western templates to paradigms grounded in Indigenous wisdom.

Quoting Deendayalji’s foundational belief that “अर्थ और काम यदि धर्म के बिना हैं, तो मोक्ष संभव नहीं,” he emphasized the need to embed economics within the framework of Dharma. He elaborated that both nature and human society are not meant for mere consumption but for meaningful, conscious coexistence. He illustrated how India’s ancient economic stability, as documented by Angus Maddison, rested on decentralized, non-exploitative systems that upheld values of restraint, interdependence, and dignity.

He warned against confusing consumerism for prosperity. Instead, he called for a value-integrated economy that cultivates not just skill, but character — where production is ethical, distribution equitable, and consumption restrained. “Kushalta se dhan aata hai, par sanskaar se uska sadupyog hota hai.”

Shri Shankarananda emphasized that education and economy must not be treated as distinct domains. The kind of economy we create is a reflection of our collective values. The idea of Atmanirbhar Bharat is not just about production but about reclaiming our civilizational agency.

He spoke of the four layers of human well-being — physical, mental, intellectual, and spiritual — and urged that economic policies must be designed to nurture all four. To do this, one must restructure not only policy but also social imagination, placing the individual not as a cog in a machine but as a co-creator in a living society.

He ended his address with a compelling affirmation: “Integral Humanism must move from being a memory to a movement. It is not just a lens to understand Bharat — it is the blueprint to rebuild her.”

Smt. Nirmala Sitharaman - Union Minister of Finance & Corporate Affairs

Reflecting on the theme “Work, Wealth, and Well-being: A People-First Economy”, Smt. Sitharaman set the tone by acknowledging that this gathering was not merely ceremonial but a moment of ideological आत्मचिंतन (self-reflection), especially as the nation observes the 60th anniversary of Panditji’s 1965 Mumbai lectures on Integral Humanism.

She emphasized the importance of these sessions for party karyakartas and policy thinkers alike. “The more we read Panditji,” she said, “the more rooted we become in our ideological foundation.” Drawing from her own experiences as a full-time karyakarta, she observed how such seminars had previously shaped her understanding, and expressed hope that today’s youth and workers would immerse themselves deeply in this philosophical vision.

Smt. Sitharaman revisited the historical backdrop of Panditji’s lectures—delivered from April 22 to 25, 1965—and encouraged everyone to re-read those four speeches, which remain relevant even six decades later. She highlighted how the BJP, as the ideological successor to the Bharatiya Jana Sangh, adopted Integral Humanism as its foundational philosophy at the 1965 Bengaluru session, marking a complete break from both Western capitalism and socialism.

Delving into the core tenets of Integral Humanism, she explained Panditji’s holistic view of the human being as comprising शरीर (body), मन (mind), बुद्धि (intellect), and आत्मा (soul). “Any model of economy or governance that overemphasizes one dimension while neglecting the others will lead to imbalance,” she asserted. This inner imbalance, when magnified across society, leads to systemic breakdown—something evident in the historical failure of both capitalism and communism.

She highlighted how capitalist economies had become unsustainable through excess consumption, environmental degradation, and deepening inequalities, while communist regimes fell prey to state monopolization and loss of individual dignity. In this ideological vacuum, Panditji presented an indigenous, Dharma-centered alternative—where ethics, decentralization, and spiritual consciousness serve as the foundation for development.

Importantly, Smt. Sitharaman brought alive Panditji’s notion of Antyodaya—the moral imperative of uplifting the last person. She reminded the audience that Panditji critiqued the Mahalanobis model of capital-intensive industrialization, which was borrowed from the Soviet Union and ill-suited for a labor-rich, capital-scarce Bharat. Instead, Panditji envisioned a decentralized economy built on self-reliant communities, small entrepreneurs, and labor-intensive industries.

She connected these early insights to the Modi government’s contemporary focus on full employment, skill development, MSME support, and digital inclusion. From monthly Rozgar Melas to initiatives like Start-Up India and PM Mudra Yojana, she outlined how the government continues to translate Integral Humanism into public policy.

Expanding on the idea of production, she explained how Panditji, inspired by Sir M. Visvesvaraya, redefined the classical factors of production. Instead of limiting it to land, labor, and capital, he proposed the “Seven Ms”: Man, Money, Material, Management, Motivation, Market, and Machine. She emphasized that these must not be imported blindly but developed in alignment with Bharatiya needs and technology.

Smt. Sitharaman pointed to current developments in AI and indigenous digital technologies as an echo of Panditji’s warning against “prefabricated” foreign models. “Retrofitting foreign technology into Indian conditions without cultural context leads to inefficiency and loss of dignity,” she warned, while celebrating India’s growing leadership in context-specific digital and financial innovation.

She further drew attention to the potter’s example often cited by Panditji—a person connected to every aspect of the production cycle, from clay to kiln to market. Unlike the modern industrial model that reduces man to a machine part, the Indian system, she said, preserves the soul in labor.

Reframing the discourse on wealth creation, she stated firmly: “Profit is not sin. Wealth is not evil. But in our civilizational framework, अर्थ must be aligned with धर्म and directed toward मोक्ष.” The role of the entrepreneur in Indian society is not to extract, but to empower — to create value without violating ethics or nature.

She invoked Panditji call for transformation: “हमारा उद्देश्य केवल संस्कृति की रक्षा नहीं, अपितु संस्कृति को गतिशील बनाना है ताकि वह युगानुकूल हो सके।” That is, our task is not merely to preserve culture, but to revitalize it so that it remains dynamic and responsive to the needs of the times. This cultural rejuvenation, she explained, is central to Prime Minister Modi’s vision of Viksit Bharat by 2047.

Finally, she addressed environmental responsibility. Long before sustainability became a global buzzword, Panditji had warned against the exploitative tendencies of both capitalism and communism. He championed Swadeshi, decentralization, and harmony with nature. Today, initiatives like Mission LiFE, renewable energy targets (46.8% capacity achieved), circular economy roadmaps, and schemes like Ayushman Bharat and PM Jan Arogya Yojana are expressions of a people-first, planet-conscious policy framework that mirror Panditji’s foresight.

In her closing remarks, Smt. Sitharaman offered a call to action:

Integral Humanism is not just relevant for 1965—it is essential for 2047. If we wish to build a developed India rooted in its soul, we must not merely inherit this ideology. We must live it, realize it, and lead with it.

Parallel Session 3A - Śikṣā and Saṃskṛti: Crafting the Global Destiny of Bhārat - Dr M S Chaitra, Director and Senior Fellow, Foundation for Study of Indian Culture, Bengaluru

In this deeply reflective session, Dr. M. S. Chaitra explored the relationship between education (śikṣā) and culture (saṃskṛti) in shaping the political, spiritual, and civilizational future of Bhārat. Drawing from Pt. Deendayal Upadhyaya’s Integral Humanism (Ekatma Mānavavāda), Dr. Chaitra emphasized that true national regeneration cannot be imagined without revisiting our foundational civilizational values embedded in our modes of teaching, learning, and being.

1. The Deceptively Simple Genius of Integral Humanism

Dr. Chaitra began by reflecting on how Deendayal Ji’s writings often appear simple but demand a deep, experiential understanding. Quoting from his own experience, he shared that the real essence of the text reveals itself only through life’s engagements, reflections, and emotional maturity.

2. The Crisis of Disconnected Engagement

He identified two common trends: Those who dismiss Deendayal Ji as irrelevant or unsophisticated. Those who claim allegiance to Integral Humanism but fail to relate it to practical politics and public life. In both cases, there is a detachment from the deeper philosophical, emotional, and civilizational vision embedded in the work.

3. Bhārat’s Role in a Shifting Global Order

Dr. Chaitra posed a provocative question: If Western models of democracy and human rights have faltered, what is Bhārat’s offering to the emerging global political order? He proposed that Integral Humanism could serve as a guiding framework for civilizationally rooted governance and education.

4. Śikṣā as a Civilizational Project

He emphasized that education cannot be reduced to skill acquisition or employment. Instead, śikṣā must nurture swabhāva (inherent disposition) and help individuals manifest their svadharma (unique purpose). For this, institutions must be rooted in Bhāratīya Chitti (civilizational consciousness) and not just modeled on colonial blueprints.

5. The Unbroken Bond Between Śikṣā and Saṃskṛti

Dr. Chaitra argued that Deendayal Ji viewed education and culture as inseparable. Culture is not merely external expression but the very process by which individuals are emotionally and intellectually trained by their social environment. This training is subtle, ambient, and continuous—not confined to formal instruction.

6. Institutional Degeneration and the Loss of Swabhāva

Drawing on personal anecdotes, Dr. Chaitra spoke of his struggles in academic spaces where traditional Indian practices were seen as out of place. He identified this as a form of cultural degeneration, where institutions fail to facilitate the natural expression of Bharatiya identity and values.

7. Rethinking Rote Learning and Memorization

Critiquing modern education policy’s obsession with eradicating memorization, he argued that Bhāratīya traditions used memorization as a powerful cognitive tool. Rote learning, when rooted in meaning and rasa, nurtures intellectual and cultural depth.

8. Language as the Soul of Civilizational Education

Language, he argued, is not just a medium but a vessel of thought, emotion, and experience. Deendayal Ji’s emphasis on bhāṣā (mother tongue) arises from this insight. Today, the lack of expressive vocabulary among youth reflects the rupture between language, experience, and knowledge.

Strategic Recommendations from the Talk

- Reclaim śikṣā as a means for manifesting the swabhāva of Bhārat, not merely for employment.

- Reimagine institutions as spaces where teacher-student relationships flourish beyond transactional frameworks.

- Reinstate language and orality as central to pedagogy, not mere carriers of content.

- Develop policies that enable lived traditions and civilizational practices to thrive in educational institutions.

- Design curricula that respect the emotional and cultural intelligence embedded in Indian forms of learning.

- Recognize that Integral Humanism is not parochial—it has the potential to contribute globally to the rethinking of education and governance.

Dr. Chaitra concluded by affirming that if the 21st century is to be Bhārat’s, it must not be on borrowed ideas but on the strength of its civilizational wisdom. The goal of śikṣā and saṃskṛti is not conformity but the free pursuit of ānanda and mokṣa. Deendayal Ji’s Integral Humanism thus provides a visionary yet grounded path for crafting Bhārat’s global destiny.

Dr. Sukanta Majumdar, Union Minister for Education & Development of North Eastern Region

In the second address on the theme “Śikṣā and Saṃskṛti: Crafting the Global Destiny of Bhārat,” Dr. Sukanta Majumdar(Union Minister of State for Education & Development of North Eastern Region) emphasized how education, language, and culture play a critical role in building a ‘Viksit Bhārat’ (Developed India) by 2047. He linked the vision of Hon. Prime Minister Narendra Modi with the philosophical framework of Integral Humanism (Ekatma Mānavavāda) as envisioned by Pt. Deendayal Upadhyaya, arguing that this framework is the civilizational compass guiding India’s educational and cultural transformation.

1. Integral Humanism as the Compass for National Development

Dr. Majumdar noted that while infrastructure and institutional development are visible markers of progress, true development is impossible without alignment with Bhāratīya swabhāva (civilizational ethos). He likened Pt. Deendayal Upadhyaya’s Integral Humanism to a compass guiding national direction, ensuring that India remains rooted while progressing.

2. Rediscovering Bhāratīya Saṃskṛti

He referred to India’s ancient continuity and cultural vitality, exemplified by artifacts like the Pashupati seal, as proof of India’s enduring civilizational consciousness. He emphasized that India’s cultural identity must be celebrated with confidence, not shame, and that PM Modi has restored pride in Bhāratīya heritage through both symbolic and policy interventions.

3. Restoring National Confidence Through Education

The National Education Policy (NEP) 2020, according to Dr. Majumdar, is not just an administrative reform but a civilizational roadmap. It aims to make education globally competitive while remaining deeply rooted in Indian ethos. He called it the “antidote to Macaulay’s vaccine,” designed to reverse the colonial mindset.

4. Emphasis on Language and Cultural Literacy

Dr. Majumdar reiterated Pt. Deendayal Upadhyaya’s view that language is not merely a communication tool, but a vessel of cultural memory, civilizational ethos, and national pride. He highlighted NEP 2020’s emphasis on mother tongue education until Grade 5 (preferably Grade 8), and multilingualism as an asset, not a burden.

5. Digital Antibody and Democratization of Education

He introduced the idea of “Digital Antyodaya” — using digital platforms like DIKSHA, SWAYAM, and Bhashini to make quality education and resources available to the remotest students and teachers. Through these platforms, students in rural areas now have access to lectures by top educators and entrance exam preparation.

6. Reclaiming Indian Knowledge Systems and Multidisciplinary Learning

NEP 2020, he explained, breaks rigid disciplinary silos by allowing students to mix humanities and sciences, making space for traditional knowledge systems. He cited how carbon dating and molecular biology are helping dismantle colonial-era myths such as the Aryan Invasion Theory.

7. Cultural Policy and Global Recognition

The International Yoga Day, the promotion of classical languages, and India’s soft power through cultural diplomacy were cited as signs of India’s civilizational revival. He recounted how Brazil’s President tweeted an image of Hanuman carrying Sanjivani as a thank-you to India’s support during the pandemic—an acknowledgment of India’s civilizational ethos in global affairs.

Dr. Majumdar concluded by reaffirming that a developed India is not possible without Bharatiya thinking at its core. NEP 2020, in his view, is the institutional embodiment of Integral Humanism, enabling the creation of a confident, value-rooted, and innovative generation. The future of Bhārat lies not in imitation but in the manifestation of its own civilizational genius, and education must serve as the vehicle for this transformation.

Parallel Session 3B - Sustainable Development: Prosperity with Ethos - Shri Prafulla Ketkar, Editor, Organiser (Weekly)

In the third keynote session on the theme Śikṣā and Saṃskṛti: Crafting the Global Destiny of Bhārat, Shri Prafulla Ketkar offered a profound reflection on how Bhāratīya knowledge traditions can provide a philosophical and sustainable alternative to the binary ideologies of the modern world. Anchoring the talk in Pt. Deendayal Upadhyaya’s Ekatma Mānav Darshan emphasized that sustainable thinking must emerge from dhārmika foundations rather than anthropocentric or exploitative models.

1. Civilizational Continuity and Humility in Indian Thought

Drawing inspiration from Kauṭilya and Deendayal Ji, the speaker highlighted the deep-rooted Indian tradition of acknowledging past thinkers and building upon inherited wisdom rather than claiming originality. This humility is central to Bhāratīya epistemology.

2. Dharma as the Foundation of Sustainability

The concept of sustainability, while recent in global discourse, is embedded in Indian thought as dharma—the principle that ensures order, balance, and continuity. Deendayal Ji analyzed both capitalism and communism and found both inadequate as they are anthropocentric and rooted in exploitation.

3. Replacing the Binary with Interconnected Holism

Unlike the Western dichotomy of individual vs. collective or man vs. nature, Ekatma Mānav Darshan proposes a framework where the individual is not central, but part of an interconnected, interdependent cosmos. The true unit is the family, not the atomized individual. This provides the moral and structural basis for a sustainable society.

4. Institutions Rooted in Bharatiya Ethos

Citing works like Badrisa Fularia’s 1920 treatise under Tilak’s influence, the talk examined how sustainable institutions have existed in Bhārat for millennia. These indigenous models influenced Deendayal Ji’s framework, which was articulated in the context of Cold War ideologies.

5. The Panchayajña Model for Civilizational Sustainability

In this model, sustainability is not merely ecological or economic—it is civilizational. Drawing from the vision of Ekatma Mānav Darshan, the speaker elaborated that Bhāratīya thought does not see humans as separate from or superior to nature. Rather, each individual is an integral part of a greater order—vyashti (individual), samashti (collective), sṛṣṭi (creation), and parameṣṭhi (the divine or cosmic order).

The Indian worldview does not promote the idea of nature as an object of consumption. Instead, it teaches that we are participants within the cosmos, not its exploiters. This ontological view has allowed Bhārat to maintain sustainable lifestyles for millennia. Restoring this vision, according to the speaker, is essential to regenerating a sustainable global future.

The speaker further emphasized that yajña is not limited to ritual; it is the selfless performance of one’s duties for others—starting from the individual, extending to family, then society, the nation, and the world. When such actions are guided by dharma and offered in the spirit of yajña, they lead to a society that no longer depends on welfare mechanisms because mutual care and contribution become foundational.

The speaker emphasized the concept of yajña beyond ritual: any selfless act that benefits another—individual, family, society, nation, or world—is yajña. A dharmic society built on such yajñas can become self-sustaining and not dependent on a welfare state.

6. The Five Domains of Swabhāva-Aligned Living

To embed swabhāva in daily life, sustainability must reflect in five personal practices: bhāṣā (language), bhūṣā (attire), bhajan (spiritual practice), bhojan (food), bhavan (housing), and bhramaṇ (travel). These practices must align with one’s natural and regional ecology.

7. An Integral Approach Across Institutions

Rajya-tantra (governance), artha-tantra (economy), nyāya-tantra (judiciary), samāja-tantra (society), and dharma-tantra (spiritual institutions) must work in complementarity rather than conflict. Ekatma Mānav Darshan promotes such an integral and inclusive approach.

8. Applying the Framework to Contemporary Challenges

While Deendayal Ji’s thoughts were developed in a Cold War context, they are even more relevant today in a post-globalization world. There is a need to bring Bhāratīya-ness into AI, patents, and emerging technologies without compromising dharma.

Shri Ketkar concluded that the civilizational challenge before India today is to reclaim and apply Ekatma Mānav Darshan to both individual life and institutional structures. If India can successfully align its education, policy, technology, and lifestyle to its swabhāva and dharmic framework, it will not only sustain itself but also guide the world in living meaningfully. The session ended with an appeal to carry this vision forward with deep reflection and practical action.

Shri Bhupendra Yadav - Union Minister of Environment, Forest and Climate Change

In a thought-provoking session, Shri Bhupender Yadav, Union Minister for Environment, Forest and Climate Change, addressed the theme “Sustainable Development: Prosperity with Ethos”, placing it within the philosophical and cultural framework of Pandit Deendayal Upadhyay’s Integral Humanism. The session highlighted how India’s environmental vision, rooted deeply in its civilizational values, aligns with the global discourse on sustainability and sets new benchmarks through action-oriented policy and grassroots initiatives.

1. Integral Humanism as the Ethical Core of Development

Marking 60 years since the articulation of Integral Humanism, Shri Yadav reiterated that Deendayal Ji envisioned a model of development anchored in Indian values—where nature is not merely a resource but a relative (bāndhava), and society is not a market but a family (Vasudhaiva Kutumbakam). Unlike the anthropocentric model of the West, which prioritizes consumption and control over nature, India’s ethos is inherently biocentric — recognizing all life forms as interconnected and sacred—and promotes harmony, restraint, and coexistence.

2. Energy and Lifestyle: Reimagining Prosperity

Over the last three centuries, human progress has revolved around increasing energy production—from coal to uranium. But this also intensified the exploitation of natural resources. Quoting Deendayal Ji, Shri Yadav emphasized that nature’s abundance has boundaries and warned against the blind pursuit of production without ethical reflection. Development, he noted, must evolve from extraction to regeneration, from consumption to balance.

3. From Western Ecology to Eastern Wisdom

The speaker traced the global ecological awakening—from anthropocentric to biocentric to deep ecology—highlighting how thinkers like Arne Næss in Norway drew inspiration from Indic philosophies. He pointed to how India has always upheld the sanctity of nature—not just through rhetoric but through rituals, values, and governance models.

4. India’s Global Leadership in Climate Action

Shri Yadav outlined India’s commitments under the Paris Agreement, including:

- A 33% reduction in carbon intensity by 2030 (achieved nine years ahead of schedule),

- A 40% share of non-fossil fuel energy (also achieved early),

- An expansive green cover and biodiversity preservation.

India’s pioneering initiatives like the International Solar Alliance, Coalition for Disaster Resilient Infrastructure (CDRI), and Mission LiFE (Lifestyle for Environment) reflect its resolve to lead the global south while balancing equity and ecological integrity.

5. Mission LiFE: Making Sustainability a Cultural Norm

Mission LiFE, launched by PM Narendra Modi, promotes environmental stewardship through everyday choices. Its seven pillars—energy conservation, water saving, food responsibility, solid and e-waste management, elimination of single-use plastics, and healthy living—translate high-level climate goals into personal ethics. Shri Yadav emphasized that sustainability is not just a policy objective but a civilizational call.

6. Sustainable Agriculture and Soil Health

Citing India’s Soil Health Card initiative, he demonstrated how localized knowledge and technological tools can regenerate land and promote responsible farming. Farmers were empowered to use fertilizers judiciously based on scientific soil diagnostics—a model blending ancient respect for soil (bhūmi) with modern science.

7. Ethical Technology and Human-Centric Growth

The talk also focused on the intersection of technology and dharma. Deendayal Ji, he noted, was never against modern tools—rather, he called for their alignment with human well-being and ecological balance. From renewable energy to AI, India’s technological pathway must be rooted in lok-kalyan (public welfare), not blind industrialism.

8. Prosperity, Equity, and Dignity for All

Quoting from Deendayal Ji’s vision, Shri Yadav reminded the audience that the economy must assure a minimum dignified standard of life to every citizen, secure national strength, and enable spiritual contribution to humanity. True prosperity, he argued, lies not in accumulation but in equitable access and ethical use.

9. Beyond Theory: Transformative Implementation

He cautioned against treating Indian thought as museum relics. Integral Humanism is not merely a doctrine—it is a blueprint for action. The speaker concluded by urging scholars, policymakers, and youth to translate dharmic values into real-world impact through innovative governance, grassroots reform, and civic participation.The session underscored that India’s developmental vision is not a borrowed model but a lived philosophy. With Integral Humanism as its guiding light, and sustainable action as its method, India is poised to lead not by dominion, but by example. As Shri Bhupender Yadav powerfully put it, “Let development be regenerative, technology be humane, and our future be rooted in our timeless ethos.”

Day 2

Session 4 - Securing Bharat: From Sovereignty of Borders to Strenght of Civilisation - Shri Nitin A. Gokhale, Founder, BharatShakti.in & StratNewsGlobal, and National Security Anayst

In a compelling and forthright session, veteran strategic affairs analyst and national security expert Shri Nitin Gokhale delved into the evolving landscape of India’s defense and foreign policy. Anchored in the context of Operation Sindhur, the session highlighted how India’s assertive posture has emerged from the assertiveness of its military responses, backed by political will and civilizational clarity. With deep insight into geopolitical motivations and operational specifics, Shri Gokhale made a case for why securing Bharat today is as much about controlling narrative and preparedness as it is about defending borders.

The session began by revisiting the tragic terrorist attack in Pahalgam, Jammu & Kashmir, which killed 26 innocent civilians. Shri Gokhale explained that this attack was not an isolated incident but part of a broader strategic shift by Pakistan. With the abrogation of Article 370 in 2019 and the normalization of Jammu & Kashmir, Pakistan saw its long-held leverage slipping. The increased integration of J&K into India’s democratic and economic mainstream, the record rise in tourism, and the improvement of local livelihoods weakened the appeal of radical elements. Pakistan responded with a calculated provocation aimed at destabilizing this progress and reigniting global attention on Kashmir.

Shri Gokhale noted how internal turmoil within Pakistan—particularly the diminishing prestige of the Pakistan Army and civil unrest—pushed its establishment to seek a conflict that could regain lost legitimacy. The logic was simple: draw India into a conflict, provoke a reaction, and reassert Pakistan’s strategic relevance. He recalled a telling anecdote from 2013, when retired Pakistani military officials expressed concern over India deprioritizing Pakistan in its strategic calculus, signaling that they desired India’s attention more than confrontation.

Operation Sindhur, as Shri Gokhale outlined, was a meticulously planned and symbolically powerful response by India. The objectives were:

- Military: To degrade the operational and psychological capacity of Pakistan-backed terrorist organizations.

- Political: To convey India’s intent and resolve that attacks will no longer go unanswered.

- Psychological: To dismantle the illusion of invincibility that groups like Jaish-e-Mohammad and Lashkar-e-Taiba operated under for decades.

One of the most significant shifts, according to Shri Gokhale, was India’s dismantling of the long-held fear of Pakistan’s nuclear blackmail. For decades, decision-makers hesitated to cross certain lines, believing any significant military retaliation might trigger a nuclear response. Operation Sindhur—executed with stand-off weapons from Indian airspace—targeted key terror infrastructure deep inside Pakistan and sent a clear message: India will act with precision, resolve, and without fear.

In the early hours of the operation, Indian forces struck nine key terrorist and military-adjacent targets within a 25-minute window, using indigenously developed weapon systems like BrahMos, Akash, and Akashteer. The Indian Air Force displayed remarkable integration of air defense systems, achieving both surprise and accuracy. Crucially, the operation maintained escalation control, despite being assertive.

He emphasized the unprecedented level of direct coordination between the political leadership—including the Prime Minister—and the three service chiefs. Frequent meetings, real-time strategy formulation, and operational freedom led to a well-executed campaign. This civil-military fusion, rarely seen before, is a new model for integrated national security management.

Despite attempts by the U.S. to intervene and take credit for brokering a ceasefire, India maintained full operational and diplomatic autonomy. Shri Gokhale clarified that what occurred was not a ceasefire in the legal sense, but a temporary pause in firing—with India retaining the right to resume if provoked. The global community was thus made aware: that every terrorist act will now be treated as an act of war.

The talk underscored that India’s security today must move beyond territorial defense to include:

- Strategic narrative control

- Cognitive warfare preparedness

- Civilisational confidence

India is no longer reacting defensively but asserting its position from a place of strength. The speaker reminded the audience that the true test of a secure nation is not in how it defends its borders alone, but in how it maintains internal cohesion, narrative sovereignty, and developmental resilience. Operation Sindhur has redefined the rules of engagement. It broke long-standing hesitations around escalation, proved the effectiveness of Indigenous defense platforms, and demonstrated strategic boldness rooted in civilizational clarity. Shri Nitin Gokhale concluded with a call for national readiness—mental, material, and narrative. He stressed that wars today are fought not just on the ground but in information spheres and public imagination.

As India rises, it must be prepared to fight alone, act alone, and win alone—not from isolation, but from sovereignty. The session reinforced the idea that Bharat’s security is not just the responsibility of the military—it is a collective civilizational commitment.

Shri K Annamalai - Former State President, BJP Tamil Nadu; Former IPS

In an intellectually stirring address titled “Securing Bharat: From Sovereignty of Borders to Strength of Civilization,” Shri K. Annamalai’s comprehensive vision of national security rooted not just in territorial defense but in India’s civilizational unity. Drawing deeply from the philosophy of Integral Humanism as propounded by Pandit Deendayal Upadhyaya, Shri Annamalai emphasized that true security lies in the preservation of Chitti — the cultural soul of Bharat—and the awakening of Virat—its collective spirit.

Referencing Pandit Deendayal Upadhyaya’s 1965 Mumbai lectures, Shri Annamalai highlighted the concepts of Chitti and Virat. Chitti represents the inherent cultural and spiritual identity of Bharat, while Virat is the awakened, collective force that rises to protect and preserve this identity.

Operation Sindhur served as a contemporary example of this Virat, where even those once advocating secession stood united with the armed forces, demonstrating the profound emotional and cultural unity of the nation.

Delving into the Bhīṣma Parva of the Mahābhārata, Annamalai drew attention to the civilizational geography of Bharatavarsha—150 river systems, 220 kingdoms, 80 mountain ranges, and 300 pilgrimage spots. These were not just territories but sacred markers of cultural integration and collective memory.

Complementing this, he cited the Viṣṇu Purāṇa’s precise description of Bharat’s north-south span as 1,000 yojanas (~3,200 km), accurately aligning with today’s map from Kashmir to Kanyakumari—affirming that our civilizational unity long preceded political unification.

Using Kashi Vishwanath Temple as a metaphor for civilizational resilience, Annamalai narrated episodes of repeated rebuilding by rulers across regions—from Bengal, Gujarat, and Karnataka, to Travancore. Despite political fragmentation, cultural unity remained robust.

From Lalitaditya’s resistance to Caliphate expansion in Kashmir, to Rani Abbakka’s defiance of Portuguese invasion in Karnataka, and the Ahoms’ defeat of Aurangzeb in Assam—the speaker showed that Bharat’s real defense has always come from a sense of shared Chitti.

Shri Annamalai criticized the growing discourse that divides India into north-south binaries based on taxation, culture, and language. He traced policies like Freight Equalization (1956–1991) that facilitated national integration by balancing industrial development. Bharat’s strength, he asserted, is not in uniformity but in its shared sacredness.

He reminded that no region is culturally superior or inferior, as evident in the distributed network of 12 Jyotirlingas and 51 Shakti Peethas. Every part of Bharat is sacred, every language rich, and every cultural thread contributes to a singular civilizational fabric.

Highlighting India’s spiritual contributions abroad, he noted how organizations like Art of Living negotiated peace in Colombia, how Isha Foundation’s mental health app outpaced global tech launches, and how Indian spiritual figures are redefining global well-being.

India’s leadership in International Yoga Day, International Meditation Day, and the International Solar Alliance are, he argued, examples of Bharat’s civilizational security architecture taking global form.

In a striking revelation, Shri Annamalai shared that India’s Army Chief reported 15% of operational time during Operation Sindhur was spent countering misinformation. He stressed that unless Indians understand and internalize their own Chitti, we will remain vulnerable to narrative manipulation. Integral Humanism, he argued, is the philosophical shield against this form of psychological warfare.

Deendayal Upadhyaya had warned against over-reliance on foreign defense technologies. Shri Annamalai noted that India’s defense production has seen a 214% increase in 10 years. Export growth has been 30-fold, and BrahMos—once 85% Russian—is now 70% Indian. With 16 nations now expressing interest in acquiring it, Bharat’s defense is becoming a beacon of technological virat.

Reflecting on the decline in mother-tongue education, particularly in Tamil Nadu, he lauded NEP’s emphasis on early learning in regional languages. Differences in language, he noted, were never a problem—politics over language is. Every Indian language holds deep literary wealth, and respecting linguistic plurality is essential to preserving Chitti.

Quoting Gandhi’s Hind Swaraj, he warned that Western civilization brings both material and spiritual decline. Unlike Mesopotamia or Rome, Bharat is still alive because of its rootedness in spiritual strength. The survival of Bharat’s civilizational dharma is itself proof of its strength.

From Make in India to Atmanirbhar Bharat, from yoga diplomacy to narrative defense, Shri Annamalai portrayed India’s resurgence as fundamentally civilizational—anchored in dignity, restraint, and rooted sovereignty.

In closing, Shri Annamalai paid homage to Pandit Deendayal Upadhyaya, whose vision of Integral Humanism continues to guide India’s journey. Political parties may rise and fall, he said, but a philosophy that aligns with truth, tradition, and collective well-being can never be defeated.

This session was not merely about security policy—it was about cultural memory, spiritual integrity, and the invincible idea of Bhārat. It called upon every young Indian to awaken to this Virat spirit and carry the flame forward.

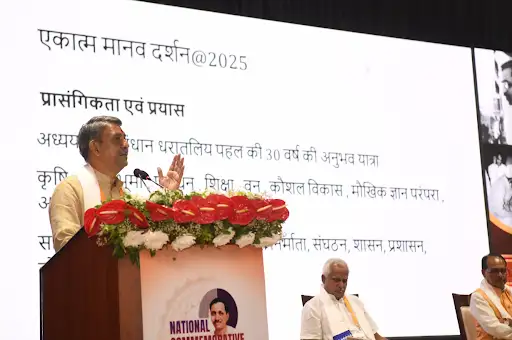

Parallel Session 5A - From Soil to Soul Sustainable Rural Development for Atmanirbhar Bharat - Dr. Gajanan Dange, President Yojak Organisation

Dr. Gajanan Dange, an experienced practitioner and scholar in the field of rural development, delivered a thought-provoking address on the theme “From Soil to Soul”—also titled Ekātm Dhārā—offering a deep civilizational and policy-linked reflection on Bharat’s agricultural and rural development journey. Drawing from three decades of grassroots engagement and inspired by Pandit Deendayal Upadhyaya’s vision of Integral Humanism, Dr. Dange emphasized the urgent need to rethink development through the lens of ecology, community wisdom, and decentralization.

Backdrop: Challenges from the Last 75 Years

The speaker critically examined India’s development trajectory post-independence, highlighting three major concerns:

- Ecological degradation: Natural resources are under severe stress, and farming has become increasingly input-intensive and unsustainable.

- Nutritional insecurity and distress migration: Malnutrition and livelihood insecurity are pushing rural populations to migrate—often not out of choice, but desperation.

- Loss of community participation: Development is now seen as the government’s responsibility alone; local agency and community stewardship are diminishing.

He stressed that the current crisis is rooted in a philosophical error—development that is disconnected from cultural values and ecological understanding.

Data and Evidence: Mapping India’s Resource Decline

Presenting maps and indices developed by Indian scientific institutions, Dr. Dange drew attention to:

- Declining Natural Resource Indexes.

- High agricultural vulnerability due to fragmented landholdings and rain-fed farming.

- Alarming dependence on edible oil imports was once a domain of self-reliance.

These indicate a systemic failure of planning rooted in cultural disconnect and short-term policy thinking.

Reviving the Civilizational Paradigm: From Dependence to Self-Reliance

Dr. Dange narrated his 30-year journey through grassroots action in agriculture, education, skill-building, and rural governance. Through initiatives across 17–18 states, he and his team have applied the principles of Integral Humanism to build localized, sustainable development models.

He emphasized:

- Swavalamban (self-reliance) and Parasparavalamban (mutual support) as essential ideas.

- Reviving community seed banks and traditional knowledge systems, especially among tribal women who possess acute ecological wisdom.

One such remarkable effort is the documentation of traditional forest knowledge among women in the Satpura region—a rare example of conserving biodiversity and cultural memory in the face of modernization and intellectual property challenges.

Narratives for a New Era: Bhūmi Supoṣaṇ and Cultural Ecology

To counter extractive and reductionist terms like “soil health” or “land use,” Dr. Dange proposed a new term: Bhūmi Supoṣaṇ (Nourishment of the Land). This idea shifts the paradigm from exploitation to care and reverence for Earth.

A pan-India campaign on Bhūmi Supoṣaṇ was launched, engaging 18,000 villages and over 5 lakh people through rituals and knowledge sessions.

The initiative is supported by major spiritual leaders like Baba Ramdev, Sri Sri Ravi Shankar, and Sadhguru Jaggi Vasudev.

Seeds, Breeds, Tools, and Techniques: Rebuilding the Rural Foundation

He identified four focal areas for intervention:

- Seeds: Reinstate the cultural and ecological practices of preserving indigenous seed varieties. He cited the example of a tribal woman who preserves 140 seed varieties, each known to her like her own children.

- Breeds: The Gokul Mission and community efforts to preserve Indian cattle breeds must be expanded. Local wisdom in selecting breeding bulls based on subtle traits must be respected.

- Tools: Mechanization must be contextual. India needs to support small, animal-powered, locally adapted tools designed for women and smallholders. IITs and engineering institutions should partner in local innovation.

- Techniques: Farming techniques should align with agro-ecological zones, water basins, and local climatic conditions—not with standard administrative boundaries.

Rebuilding Relationship with Resources: From Commodification to Reverence

Dr. Dange underlined the cultural ethos that treats land, water, and biodiversity as sacred—not as extractable resources. He called for reviving agricultural festivals that signify ecological cycles, like:

- Ambuvachi in Assam

- Rajrani Snan in Kashmir

- Raja Parba in Odisha

- Gauri Festival in Maharashtra

These celebrate the menstruation and rest cycles of Earth—a deeply ecological and sacred concept. To integrate ecological awareness in youth and policy, Dr. Dange shared two major initiatives:

- Curriculum: “Apna Parisār, Apni Pahchān” – A structured program to help youth recognize their agroecological identity before administrative labels.

- Leadership Development: A “Preraṇā-vr̥tti” program to develop rural youth as vikās netās (developmental leaders) rooted in ecology, not merely electoral politics.

Dr. Dange concluded with a stirring message:

भारत के गाँवों में आज भी प्रज्ञा जीवित है। बस विश्वास और श्रद्धा की आवश्यकता है। वे भारत को ठीक कर देंगे।

He emphasized that rural wisdom, when trusted and empowered, can not only reverse degradation but also offer the world a civilizational path toward harmony, sustainability, and dignity.

Shri Shivraj Singh Chouhan - Union Minister of Agriculture & Farmers Welfare, Minister of Rural Development

In his address on Sustainable Rural Development for Ātmanirbhar Bhārat, Shri Shivraj Singh Chouhan outlined a clear, actionable, and culturally rooted vision for transforming Bharat’s rural landscape. Going beyond economic metrics, he emphasized that true self-reliance (Ātmanirbhartā) must begin from the soil upwards—grounded in Bharat’s civilizational values, community wisdom, and ecological balance.

With humility and experience drawn from both policy and practice, he called for a model of rural development that honors the dignity of the farmer, empowers the village as the basic unit of governance, and reorients agriculture toward sustainability, nutrition, and resilience.

1. Villages as the Heart of Bharat

Shri Chouhan began with an emphatic assertion: “If Bharat has to rise, its villages must thrive.” Citing Gandhian ideals and the legacy of thinkers like Pandit Deendayal Upadhyaya, he reminded the audience that Bharat is not a nation built around cities but around its 6.5 lakh villages, each with its own identity, wisdom, and strength.

2. Reframing Agriculture: From Food Security to Farmer Prosperity

The Hon’ble Minister emphasized the need to shift from a production-centric approach to a value-centric approach in agriculture:

- Encourage diversification over monoculture.

- Promote nutri-cereals (millets) and indigenous crop varieties for both ecological and nutritional security.

- Ensure value addition at the local level so that wealth remains within the village economy.

He underlined the need to restore dignity to farming, not just through income enhancement but through respect and recognition of the farmer’s role as an annadāta and jñānadāta.

3. Five Pillars of Sustainable Rural Development

Shri Chouhan outlined a five-fold strategy to achieve self-reliant rural ecosystems:

- Gaon ki Sashakt Sthāpit Vyavasthā (Empowered Local Governance): Strengthen Panchayati Raj institutions as planning and execution centers.

- Jal, Jungle, Zameen ka Samvārdhan (Natural Resource Restoration): Prioritize watershed management, organic farming, and regenerative practices.

- Mahilā Evam Yuva Shakti ka Sashaktikaran (Empowerment of Women and Youth): Skilling and entrepreneurship programs must center around agro-based rural industries.

- Grāmīṇ Rachnā mein Nāgarik Bhāgīdāri (Civic Participation in Rural Design): Encourage community ownership of development through rituals, festivals, and local stewardship.

- Sahakār aur Swavlamban (Cooperation and Self-reliance): Revive the cooperative movement with 21st-century tools—digital agriculture, farmer-producer organizations (FPOs), and local marketing platforms.

4. Cultural Roots, Civilizational Strength

In a particularly evocative moment, he said, “Bharat ke grām hamesha se dharm aur dharti ke sūtra mein jure rahe hain”. He spoke about the need to re-awaken the cultural spirit of the village—its utsavs, oral traditions, crafts, and ecological festivals—as essential to any model of sustainability.

He stressed that sustainability in Bharat is not a new concept, but something deeply embedded in practices like Gau-sevā, Van Mahotsav, Panchmukhi Yojanas, and local food traditions that align health with nature.

Vision Forward: Policy Meets Philosophy

Shri Chouhan concluded with a call for integrating policy with philosophy. He proposed that:

- Development programs are tailored to agroecological zones rather than administrative zones.

- Youth fellowships and academic programs are designed to bring young minds back into rural innovation.

Each district is supported to prepare a Gramodaya Plan that reflects its ecological capacity, cultural strengths, and economic potential.

This session offered a compelling blueprint for Ātmanirbhar Bhārat—not as a slogan but as a civilizational renaissance rooted in its villages. Shri Shivraj Singh Chouhan’s address served as a powerful reminder that sustainable rural development is not just about policy frameworks—it is a moral and cultural imperative, one that must be carried forward with pride, participation, and purpose.

Parallel Session 5B - Women and Youth Power, Potential and Purpose - Smt Mamata Yadav, Member, Haryana Public Service Commission

In her address titled “Women and Youth: Power, Potential, and Purpose,” Smt. Mamata Yadav spoke with clarity, conviction, and deep cultural insight on the role of two of the most vital segments of Bharat’s society. Her talk offered not only a diagnosis of current challenges but a call for rediscovering the innate strengths of women and youth through the lens of samskāra, self-confidence, and svasthata (wholeness).

1. A Generation Caught Between Noise and Direction

Smt. Yadav began by acknowledging the current emotional and intellectual confusion that many young Indians face. The overwhelming noise of social media, information excess, and directionless comparison has created a generation that is informed but not always empowered.

She emphasized the need to go beyond productivity-driven metrics to understand the inner compass of youth—a sense of purpose rooted in identity, belonging, and dharmic values.

2. Rediscovering the Dignity of Womanhood

Touching on the state of women in modern discourse, Smt. Yadav remarked how the narrative has shifted from strength to victimhood. She invited the audience to remember that the Bharatiya woman has never needed to ask for empowerment—she is power (śakti). What she needs is societal structures that recognize and nurture her integral roles—as creator, preserver, and guide.

Quoting examples from Bharatiya history and daily life, she reminded that women are not mere beneficiaries of welfare but carriers of wisdom and anchors of continuity.

3. The Inner Life of the Youth: From Aspiration to Realization

Smt. Yadav stressed that today’s youth must first discover their inner discipline, rather than chase abstract ideals. She observed that the purpose of education is not the accumulation of information, but the cultivation of viveka (discernment).

She challenged educational institutions to shift from grading intellects to shaping character and courage, encouraging the audience to see students not as empty vessels to be filled, but as sparks waiting to be kindled.

4. Moving from Rights to Responsibility

In a powerful reflection, she noted how the overemphasis on rights in popular discourse has made people forget the civilizational importance of responsibility (kartavya). A culture thrives not when people demand more from the state, but when individuals offer more to society—from the ground up.

Both women and youth, she said, have a natural tendency toward care and creation—and our national frameworks must channel this potential not through restriction, but purposeful engagement.

5. The Civilizational Compass

Echoing the theme of the larger event, Smt. Yadav insisted that India’s pathways to empowerment cannot be borrowed from Western models of development, feminism, or progress. Bharatiya civilization, she argued, offers its own frameworks—where the family is not a burden, the community is not regressive, and dharma is not outdated.

In this vision, youth are torchbearers, not rebels; women are creators of harmony, not merely recipients of inclusion. Smt. Mamata Yadav’s address was both an invocation and a roadmap. Her message to the youth was not one of instruction, but inspiration: “You are not incomplete beings waiting for validation. You are the ones this land is waiting for—find your śakti, find your kartavya, and the nation will rise through you.”

Her words left the audience with a renewed faith in Bharatiya womanhood and youth—each a pillar of purpose, resilience, and untapped greatness.

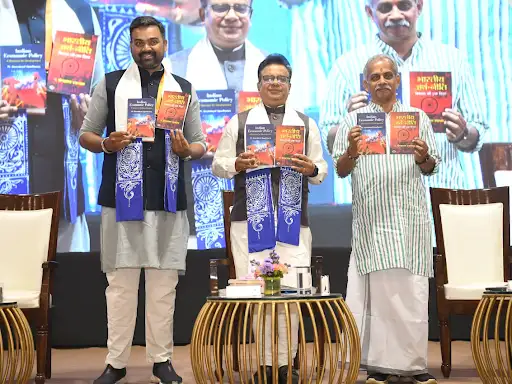

Shri Abhinav Prakash - National Vice President BJYM; Assistant Professor of Economics, Delhi University

In a thought-provoking session delivered as part of the seminar on Ekatma Manav Darshan (Integral Humanism), Shri Abhinav Prakash—economist, academic, and public intellectual—addressed the audience on the power, potential, and purpose of India’s youth and women in shaping the national future. Rooted in the philosophy of Pandit Deendayal Upadhyaya, his talk examined the historical wounds of India’s civilization, articulated the role of youth in national rejuvenation, and explored how Integral Humanism offers a living framework for responding to modern-day challenges.

Eschewing abstract theorizing, Shri Prakash presented a grounded yet visionary address that wove together history, political economy, and civilizational insights, calling upon the youth to become conscious actors in the unfolding destiny of the nation.

1. Historical Context and the Need for Rejuvenation

Shri Prakash began by situating the role of youth within India’s long civilizational timeline, emphasizing that the past thousand years have left India deeply wounded. Repeated foreign invasions—whether by the Turks, Mughals, or the British—brought about a loss of sovereignty, cultural trauma, and economic destruction. He cited the Bengal Famine of 1770, following the British conquest, as a case of catastrophic colonial plunder. India, he argued, is a civilization that has survived against great odds, and the youth must now lead its regeneration.

2. The Fourfold Purpose of Youth in National Life

He identified four key responsibilities that today’s youth must embrace to fulfill their historic role:

- Sovereignty and Territorial Integrity: India’s geographical unity cannot be taken for granted. History teaches us that constant vigilance and national strength are essential for preserving sovereignty.

- Economic Prosperity: Generations of deprivation have not only resulted in poverty but physical and biological setbacks due to malnutrition. Youth must lead the way in building a prosperous India rooted in self-reliance and innovation.

- Cultural Consciousness: A renaissance of cultural identity is critical. Youth must reconnect with their roots—not to retreat into the past, but to carry forward India’s civilizational ethos with clarity and creativity.

- Social Egalitarianism: Despite progress, inequalities persist. The youth must work towards a just society by upholding dignity and fraternity in public and private life.

3. Integral Humanism as the Guiding Framework

Shri Prakash then turned to Pandit Deendayal Upadhyaya’s Ekatma Manav Darshan as the philosophical anchor that harmonizes individual aspirations with national needs. He distilled the complex philosophy into key tenets:

- Holism over Atomism: Unlike Western ideologies that reduce society to a sum of individuals, Integral Humanism views society as an organic whole—like the Virāṭa Puruṣa, where each part (individual, collective, and soul) is interdependent and meaningful only in relation to the whole.

- Integral Development of the Human Being: True progress must address not just the body and mind, but also the intellect (buddhi) and soul (ātma). Today’s fragmented life, he said, is responsible for the rising mental health crisis, and Integral Humanism offers a path to reintegration.

- Cultural Specificity in Policy: He illustrated how cultural context matters in shaping institutions. For example, Western privacy laws emerge from a history of violence and social detachment, whereas India’s cultural norms value relational harmony. Blind policy importation, he warned, can be counterproductive.

4. Youth Shakti: Physical, Moral, and Mobilizational Power

The speaker emphasized that youth power (shakti) lies in three areas:

- Physical and Intellectual Vitality: As the most dynamic part of the nation-body, youth are the driving force of innovation and resilience.

- Moral Dynamism: Youth possess an instinct for idealism, but it must be grounded in Indian moral frameworks. He cautioned against the uncritical adoption of Western ideas of liberty, noting that the Indian Constitution is centered on justice, not just individual freedoms.

- Mobilization Capacity: In India, society has historically been stronger than the state. The youth must build civic power through volunteering and social leadership—independent of state structures—to ensure cultural and social continuity.

5. Relevance to Contemporary Challenges

Shri Prakash offered powerful insights into how Integral Humanism can address modern challenges:

- Artificial Intelligence: The philosophy calls for culturally anchored algorithms, national data sovereignty, and ethical frameworks rooted in dharma.

- Mental Health: The current crisis, he said, stems from overemphasis on the body and emotions, neglecting intellect and spirit. The remedy lies in holistic self-development through community engagement, yoga, and purpose-driven action.

6. Encouragement of Political Participation

In concluding this segment, he lauded recent efforts to invite youth into politics from non-political backgrounds. This, he argued, is the final bastion where feudalism still lingers and must be dismantled. Youth energy, he said, can reimagine Indian politics by aligning it with the aspirations of a vibrant and self-confident nation. Shri Abhinav Prakash’s address was a clarion call to India’s youth to rise beyond careers, comforts, and borrowed ideologies—to embrace their civilizational responsibilities with intellectual clarity, cultural rootedness, and ethical action. Through a lucid interpretation of Integral Humanism, he reminded the audience that India’s future will not be shaped merely in economic or political terms but through a harmonious alignment of the individual with the collective and the national soul.

He concluded with the powerful assertion that the youth must:

- Lift the last Indian (Antyodaya)

- Guard the nation’s soul (Chitti) and territory

- Sustain the planet

- Align their body, mind, intellect, and soul with the collective swabhāva of the nation. In doing so, they will not only secure a strong and prosperous India but also participate in one of the most important civilizational renewals of our time.

Session 6 - Legacy of Leadership, Nationalism, and Social Justice - Shri J Nandakumar, National Convener, Prajna Pravah

In a deeply reflective and incisive address, Shri J. Nandakumar explored the cultural and spiritual roots of Indian nationalism, situating it within the broader legacy of leadership and the enduring quest for social justice. Drawing from the Vedas, India’s philosophical heritage, and the contributions of spiritual and political visionaries like Adi Shankaracharya, Swami Vivekananda, Guruji Golwalkar, and Pandit Deendayal Upadhyaya, his talk offered a profound re-articulation of Rashtra—the Indian nation—not merely as a geopolitical entity, but as a civilizational force animated by dharma, chitti (national soul), and samskriti (culture).

Shri Nandakumar began with a quiet yet firm reminder that our discussions on nationhood must not remain confined to administrative or constitutional frameworks. They must begin with introspection. “It is a great occasion for us all to think again and again about the fundamental philosophy on which we are working together,” he said. Indian nationalism, he stressed, is not an outgrowth of temporary alliances or colonial restructuring. It is not a reaction. It is an expression—a Darshana—that predates modern political frameworks and carries within it the spiritual labor of millennia.

The Western concept of the nation, he noted, often arises from contracts of mutual interest, competition, or colonial conquest. It is shaped by the logic of economics, military ambition, or commercial expansion. In contrast, Indian nationhood arises from a shared spiritual vision. “Our Rashtra,” he declared, “is not the creation of kings or armies—it is the creation of Rishis through Tapasya.”

Quoting a powerful Vedic mantra—Tapo dīkṣām upaseduḥ agre, tato rāṣṭram…—he emphasized that the very birth of the Indian nation is attributed to the selfless austerities of sages who desired the well-being of all beings. “Rāṣṭra,” in this view, is not just territory—it is the outcome of tapas, of a sacred resolve to manifest a just and harmonious society, blessed even by the Devas.

This philosophical foundation, he explained, is the reason why Indian nationalism has historically been a force for integration rather than domination. While the Western world saw nationalism descend into fascism, racism, and wars, the Indian worldview fostered cooperation, peace, and dignity. As he succinctly put it, “India’s national expansion never occurred through subjugation or violence, but through gentle cultural influence—like the dew that falls unseen and unheard, bringing life to every petal,” echoing Swami Vivekananda’s metaphor.

The speaker critically examined distorted interpretations of Indian history that have attempted to reduce India to a colonial construct. “We must be cautious of those,” he warned, “who say that India came into being in 1947. To accept such a view is to deny the very essence of our civilization.” Citing instances of influential public figures claiming India was “only a landmass between Burma and Afghanistan,” he called out the dangerous erosion of historical consciousness. “If India was a mere landmass,” he questioned, “what was the purpose of our freedom struggle? What were our sages and revolutionaries fighting for?”

He offered a layered response to these narratives by categorizing contemporary attitudes into three types: the Navarashtravadis who see India as a new-born nation; the Bahurashtravadis who deny the unity of India and see it as a federation of many sub-nationalities; and the Chirashtravadis, to whom India is an eternal, spiritual, and cultural Rashtra. “The Rashtra is not new. It is not constructed—it is realized. Its foundation is not political conquest but cultural continuity and spiritual striving,” he said.

From the Vedic sages to Swami Vivekananda and Pandit Deendayal Upadhyaya, the thread of this civilizational nationalism continues unbroken. Swami Vivekananda, whose words were quoted with resonance, once said: “Renunciation and service are the national ideals of India. If you want to strengthen the nation, strengthen her in those channels.” These are not empty moral exhortations but concrete national duties. In Vivekananda’s Madras speech (1897), he invoked Bharat Mata not as a symbol of territorial pride but as a living deity: “Let all other gods vanish for the time being; this is our God—our own race, our own nation.”

The divine framing of India—Bhārata Mātā as Devī—was not merely poetic sentiment. It was, Shri Nandakumar argued, a civilizational recognition of the feminine principle of nurturing, sustaining, and transforming. Adi Shankaracharya too, in Saundarya Lahari, depicted Indian cities as manifestations of the Goddess. In this view, patriotism becomes a sacred offering, and service to the nation becomes a form of seva to the divine.

Turning to the thoughts of Pandit Deendayal Upadhyaya, he highlighted how Ekatma Manav Darshan draws on this spiritual foundation. For Deendayal ji, the nation is not just a structure—it is a living organism, animated by chitti, the collective consciousness and essence of a people. “Chitti,” he explained, “is the touchstone on which every action and attitude must be tested. It is the soul of the nation.”

Deendayal ji asserted that like an individual possesses an inner self or swabhāva, a nation too has a soul—an innate nature—that cannot be altered by changing governments or global events. This cultural selfhood, once awakened, should guide development—not merely for economic progress but for harmony, justice, and upliftment. “We must no doubt build dams and factories,” he once said, “but what is more important is to provide a philosophy of life to the country that revives Indian idealism.”

In addressing social justice, Shri Nandakumar departed from the narrow political lens and invoked the Indic understanding. Justice, in the Bharatiya tradition, is not about appeasement or reparation—it is about dharma, about inner dignity, about ensuring that no one is alienated from the cultural whole. The vision of nationalism he presented was thus not exclusionary but integrative—drawing even from the thoughts of Dr. B. R. Ambedkar, who, in his Columbia seminar, emphasized that India’s unity is not geographic alone, but cultural and moral.

“India has always been an inclusive civilization,” he concluded. “Our nationalism is spiritual, our leadership arises from renunciation, and our social justice flows from dharma. This is the legacy we inherit—not from 1947—but from the very beginning of our civilizational journey.”

As the session ended, there lingered a quiet clarity: that the task before today’s youth, leaders, and thinkers is not to reinvent India—but to remember her, to live out her truths in action, and to strengthen the Rashtra by walking its eternal path of selfless service, cultural rootedness, and fearless clarity.

Dr Guru Prakash Paswan, National Spokeperson, BJP, Assistant Professor of Law, Patna University

In a session that blended historical insight, philosophical depth, and piercing contemporary relevance, Dr. Guru Prasad Paswan offered a compelling narrative on the enduring relationship between nationalism and social justice, under the evocative theme “Legacy of Leadership”. Delivered in the presence of esteemed scholars like Shri Nand Kumar Ji and Shri Shiv Shakti Bakshi Ji, Dr. Paswan’s address was not only a scholarly intervention but also a moral invitation to reframe public discourse around ideas of unity, dignity, and inclusive nationhood.

Dr. Paswan began by acknowledging the intellectual contributions of the other panelists, noting how Shri Nand Kumar Ji’s writings—especially Hindutva for the Changing Times—had equipped many with answers to deep civilizational questions. He emphasized that such discussions on nationalism and justice are possible only in intellectually open and culturally rooted spaces, where dialogue is not bound by ideological echo chambers.

He set the context by highlighting the historical significance of the moment: 60 years of Integral Humanism, 75 years of the Indian Constitution, and the centenary year of Atal Bihari Vajpayee. These overlapping anniversaries, he suggested, are not just commemorative but catalytic—providing the moral ground to reflect on where we’ve been, where we stand, and where we wish to go as a nation.

Addressing a common skepticism, Dr. Paswan dismantled the false binary often drawn between nationalism and social justice. He cited contemporary reactions to policies like the caste census and observed that many assume that a nationalist commitment is incompatible with a commitment to equity. This, he argued, reveals a deep misunderstanding of Indian political and philosophical traditions.

Drawing from the lives and thoughts of Babasaheb Ambedkar and Pandit Deendayal Upadhyaya, Dr. Paswan illuminated how both these leaders—often framed in ideological opposition—actually converge at crucial points. Both hailed from socially disadvantaged backgrounds. Both were ignored for decades by dominant academic narratives. And both envisioned an India rooted in cultural unity but committed to justice and dignity for all.

Quoting from Ambedkar’s Writings and Speeches, Dr. Paswan reminded the audience that Ambedkar was deeply inspired by Ramanujacharya, especially for accepting a so-called lower-caste guru. This act, Ambedkar said, symbolized “spiritual democracy.” Simultaneously, Pandit Deendayal drew his metaphysical inspiration from Adi Shankaracharya. While their influences were different, the philosophical core—of oneness, unity, and dignity—was the same.