One of the most complex areas at the intersection of ethics, morality, medicine, and law is the induced termination of pregnancy, or abortion. Two lives entangle as one unit, and a clash sets up between the autonomy of a mother, who can raise her voice, and a dependent fetus, who cannot speak at all. As various groups advocate for the rights of the silent fetus, the concept and essence of motherhood seem to fade from the discourse occasionally.

Politics, society, law, medicine, ethics, morals, religions, and human rights make for a complex cocktail of raging emotions, disparate voices, and fights of all kinds. Rights and wrongs are difficult to decide, of course, as is the case in many debates. A consensus statement is unlikely anytime soon. Essentially, the debate is regarding a contradiction between the two fundamental properties of a liberal life: the freedom to choose (for the mother) and the right to live (for the fetus).

Many factors converge on the debate, especially in the West. Political ideologies like the right-wing, pro-life, and ‘no right to abort’ ideology versus the left-wing, pro-choice, ‘right to abort’ one; religious affiliations, like the strict anti-abortion stance of Catholics versus allowing abortion stance of Protestants; and socio-cultural factors, such as 50% of mothers being unwed in the USA; all play a role in this vigorous debate. Conceptions arising out of wedlock are still not prominent in a country like India, though their numbers may slowly increase in the decades to come.

The Debate in the USA

As noted above, essentially, the debate is regarding a contradiction between the two fundamental properties of a liberal life: the freedom to choose and the right to live. In 1973, a lady from Texas, USA, Norma McCorvey (anonymously named Jane Roe), challenged the Supreme Court against a universal law that made abortion illegal. The state representative of Texas was District Attorney Henry Wade. She won the case when the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that the Constitution, under the right to privacy protected by the 14th Amendment, protects a woman's right to choose an abortion. This established a federal constitutional right to abortion. However, in 2022, the Supreme Court overturned this right, leaving individual states to determine abortion laws. Today, abortion laws in the USA vary from state to state, ranging from providing free access to abortion to severely restricting it.

The legal guidelines for terminating a pregnancy following this famous Roe v. Wade case were a pragmatic view and not based on any moral, ethical, or religious ideas. The right to live (for the fetus) was considered vital in the later part of pregnancy, as was the freedom to choose (for the mother) in the early part. The argument failed to address the potential conflict and the slippery slope that arises when each side pushes for either the freedom to choose or the right to live throughout all stages of pregnancy.

Both the so-called right wing (pro-life or no right to abort) and the so-called left wing (pro-choice or right to abort) adopt strong positions that clearly define their differences. Religious denomination also comes into play. Catholics categorically do not support abortion. In a predominantly Catholic Ireland, an Indian dentist was refused an abortion in 2012 on religious grounds, and she died due to sepsis. The incident led to widespread controversy across the world, and the Irish parliament introduced some changes to the law allowing abortion in case of medical danger to the mother. Protestant churches have a variable stand on the issue, ranging from opposition to complete support. Compromise seems hardly possible, as offence comes easily with any stance. This is a significant issue in Western countries, particularly in the US.

In the abortion debate, the US Supreme Court does not consider whether human life or personhood begins at conception, birth, or at some point in between. The 24-week guideline is on the ‘survivability’ of the fetus outside the womb and, specifically, the fetus’ lung maturity to take breaths. Scientist Carl Sagan (Abortion: Is It Possible to Be Both Pro-Life and Pro-Choice) proposes 24 weeks, but for different reasons. He considers the research pointing out that at 24 weeks the foetal brain starts showing well-formed brain waves typical of an adult human being, and that might declare the transition of a fetus to a ‘proper person’.

Carl Sagan puts two questions here. First, why should breathing only justify legal protection? If one shows that a fetus can think and feel but cannot breathe, would it be all right to abort them? Second, with better technology, a fetus might survive at a much younger gestational age. This is definitely happening now. The world record stands at 21 weeks of gestation, which is just above 5 months only. Earlier gestation babies and low birth weight babies (as low as 500 grams) are a routine occurrence in many parts of the world, including India. As technology advances, the survivability criteria will shift to lower ages, possibly making previously immoral abortions moral. Sagan says, A morality that depends on and changes with technology is a fragile morality; for some, it is also an unacceptable morality.

The Indian Scenario

The Indian Medical Termination of Pregnancy (MTP) Act, formulated in 1971, made the legal limit 20 weeks purely on the consideration that after this age, terminations can be unsafe for the mother. Recently, it has gone up to 24 weeks to allow a wider timeframe and relieve the pressure of a narrow window for diagnosing many serious foetal anomalies.

The discrepancy in the Indian rules arises from three considerations. First, termination is now safe even at later stages of pregnancy; but the rule has seen an extreme resistance to updating based solely on this ‘safety to the mother’ criteria. Second, many foetal anomalies —some serious and difficult — in the Indian scenario have a diagnosis between 20 and 24 weeks with the application of the latest in the field of antenatal testing, including genetic analysis. This situation puts severe stress on both the doctors and the affected families when there is potential confrontation with the law. Third, the conflation of the MTP Act - established with the intention of safe and legal abortions - with the PCPNDT Act - the Pre-Conception and Pre-Natal Diagnostic Techniques Act, established with the intention of preventing gender-based selective abortions - has many implications for women's access to safe abortion services. We will explore some nuances of the PCPNDT Act below.

In 2021, there was an amendment to the MTP Act that extended the upper gestational limit from 20 to 24 weeks for certain categories of women, specifically survivors of rape and incest, and other vulnerable women like minors, disabled women, and women with congenital foetal defects. Additionally, in 2022, the Supreme Court allowed unmarried women and single women to access legal abortion care until 24 weeks of gestation.

Antenatal Diagnosis, Termination Of Pregnancy, and Ethical Issues

Across time and cultures, generally, abortion to save the mother's life has been unambiguous. Antenatal diagnosis raises ethical issues in this complex situation. With technologies probing increasingly deeper into the fetus, there is pressure to demonstrate that the fetus is normal. The readiness to abort babies with even the slightest of problems sometimes stems from the fundamental philosophy that preventing birth would save money compared to the care of these children who may be physically or mentally disabled. This is more rational-economic thinking than anything else.

Technology today has expanded the category of unacceptable abnormality and narrowed the range of acceptable normality. Previously, a fetus was assumed normal, and the abnormality needed proving.

Almost a complete reversal of attitudes has occurred, with the assumption now being that a fetus is abnormal and the establishment of normality necessary!

Primary medical ethics demand that life or no life is never an option for any disease. But in foetal medicine, abortions are a very active option. Is it in the interests of the fetus, mother, or society? Thus, the disturbing problem with foetal screening and selective abortion is that in many cases, one cannot eradicate the disease without eliminating the subject.

Selective abortion has affected research on several rare diseases, especially neurodegenerative disorders. The selective abortion of such fetuses has removed the incentive to do further research on the disease itself, leading to the suffering of people who are afflicted with it or born without the benefit of foetal medical care.

Imagine a hypothetical future scenario: Based on genetic analysis, the doctor declares that the fetus is going to become a severe alcoholic, have homicidal tendencies, or have major gender issues later in life. How many parents would opt to continue with the pregnancy? How many alcoholics or transgender people would remain in society over a gradual period, if elimination in fetal stage is possible? These options are not completely possible today, but the future of science and genetics is distinctly optimistic.

Of course, some authors deny claims about the discovery of genes for complex human traits like sexual orientation or alcoholism. They argue that such claims are pseudoscience. These authorities feel that the genetic code is very complex for most human traits, with hundreds and thousands of genes involved in each single human trait. Furthermore, all the genes interact in a highly complicated manner with the environment they are in. The paradigm of one gene leading a specific trait or disease simply cannot cover the complex behaviour of humans. However, science has many times whacked someone who said, It’s impossible.

Ethical Quandaries in Down Syndrome

Every year, the world celebrates World Down Syndrome Day on March 21. The agenda is that the Down syndrome population must have opportunities to live fulfilling lives and be included on a full and equal basis with others in all aspects of society. However, the way society is dealing with the Down syndrome population goes completely against the 2030 UN Agenda for Sustainable Development - a global plan of action for people, planet, and prosperity, pledging that “no one will be left behind”. The sad fact is that individuals with Down syndrome struggle with all aspects of their lives, especially education and employment.

Their wholesome acceptance and integration into society are also matters of considerable difficulty.

Down syndrome children can express extreme love and contentment towards their family and society, but they do have varying levels of intellectual impairment. However, there is a need for a worldwide study, on living Down syndrome patients, to assess their perspective.

A small study of 284 children with Down syndrome over 12 years of age titled Self-perceptions from People with Down Syndrome showed that nearly 99% of people with the syndrome were happy with their lives; 97% liked who they are; and 96% liked how they look. Nearly 99% of people with Down syndrome expressed love for their families, and 97% liked their siblings. While 86% of people with the syndrome felt they could make friends easily, those who faced challenges often lived in isolating environments. Only a small percentage expressed sadness about their lives, even though the overwhelming majority of people surveyed indicated a joyful and fulfilling life.

This is indeed concerning, as the number of babies born with Down syndrome is steadily declining. The entire antenatal screening strategy, including blood tests on the pregnant mother, ultrasound scans, and genetic analysis on the foetal tissues, is targeted worldwide to detect Down syndrome and then terminate it.

One author puts it succinctly as a “search-and-destroy” technology.

Not only in India, but in advanced countries like Europe and America, the termination of these babies has become the norm. Iceland has almost achieved a 100% elimination rate for Down syndrome.

After a diagnosis of Down syndrome, the counselling by the medical fraternity - instead of giving the family options - is heavily biased towards terminating the pregnancy. Most families comply with this. It is not any malicious intention on the part of the medical profession, but simply the moral and ethical worry of continuing a pregnancy that is going to deliver an ‘abnormal’ baby. So here comes the enormous ethical quandary and paradox -

On the one hand, we are trying to integrate the Down syndrome population into society by calling them equal, but on the other, we are doing the best possible to prevent them from being born.

There is a strong global group which feels that no Down syndrome fetus should be terminated. They advocate that fetal diagnosis should only prepare the parents and society to receive the baby. It is, of course, highly utopian in the present society. The ethical justification for aborting a Down syndrome baby (or any other malformation) because it will be a burden on the family is disturbingly ambiguous; because the same logic can apply to a female child, for example, causing a great disturbance to the social life of some mothers.

Some ethicists say there is no difference in such scenarios between female infanticide and terminating for Down syndrome.

It is a difficult situation for society when families with a Down syndrome diagnosis in the fetus, medical professionals, and government machinery interact in many discordant voices. The ethical, moral, legal, medical, and social dimensions of solving these paradoxes need a more detailed and nuanced discussion. Down syndrome is one prototypical example, of course. The ethical problems and issues are going to only increase in the future as more diseases enter the domain of pre-delivery diagnosis.

Female Feticide

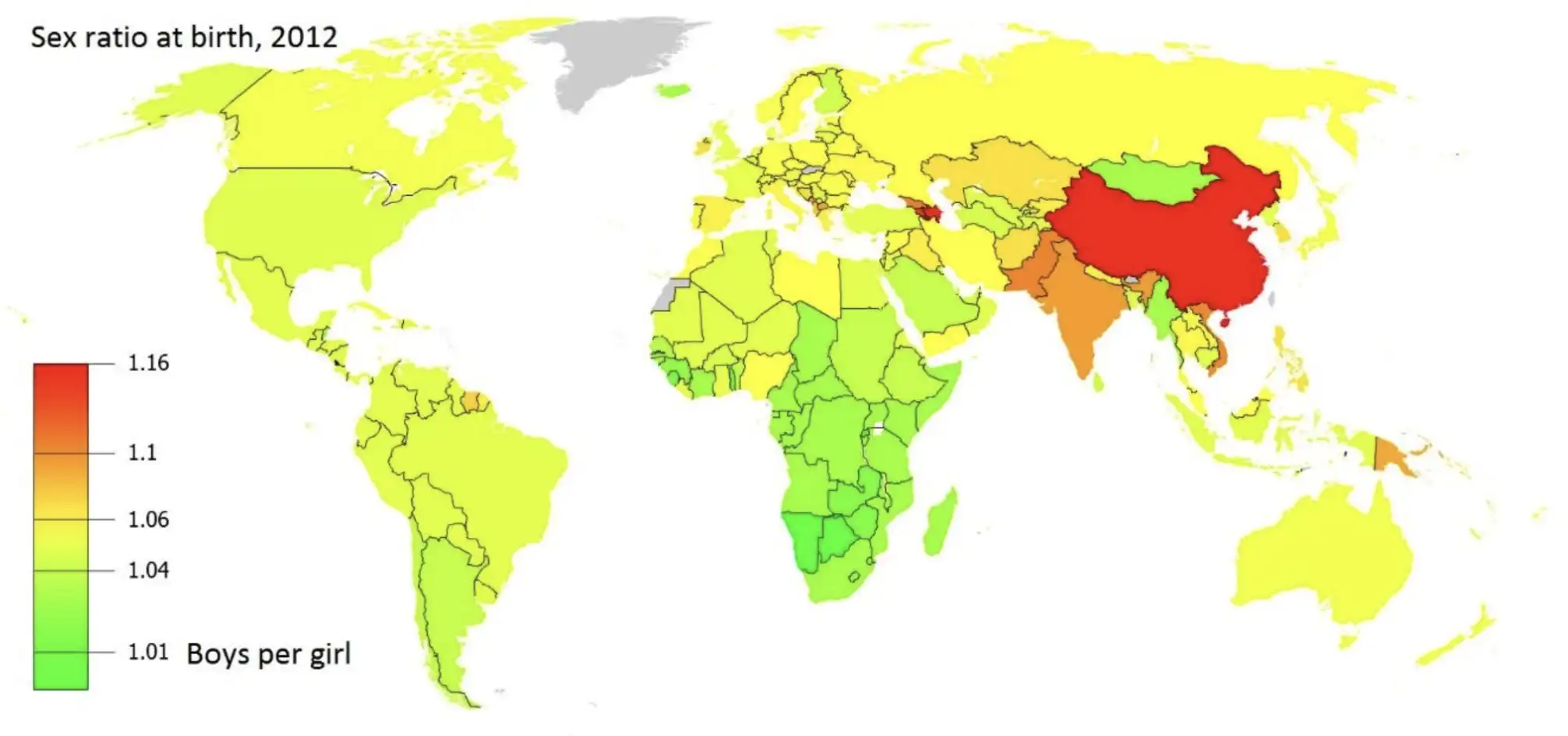

The Pre-Conception and Pre-Natal Diagnostic Techniques (PCPNDT) Act, enacted in 1994, was established with the original intention of preventing female feticide, by strictly regulating pre-natal diagnostic techniques. The issue has undoubtedly become a significant debate for radiologists in India. The imbalance in favor of boys at birth - in India and China - has resulted from a combination of many social and medical factors. The government implemented the PCPNDT Act to prevent ultrasonologists from revealing the child's sex.

However, many times, there are fetal problems diagnosed where knowledge of the sex of the child plays an important role in prognosticating further on the disease, and in counselling of the family. Nevertheless, as per the PCPNDT Act, the ultrasonologist cannot reveal the sex of the child. The situation is akin to an astronomer being allowed to study all the stars, but not being allowed to even look at the plainly visible moon! Interestingly, in Western countries - where the child’s sex is routinely revealed during pregnancy if the parents so choose- the ultrasonologist reveals the sex of the fetus, if the parents desire to prepare accordingly to receive the child. Though sometimes in the West, just for the sake of suspense, parents do not desire to know the sex of the child when there are no other concerns. Such attitudes may reflect a more mature society, or simply a different cultural perspective.

While the PCPNDT Act is intended to prevent female feticide, it places the accountability of any given female feticide on the radiologist or ultrasonographer - simply for revealing the sex of the child. Some argue that, perhaps, the system can be crafted a bit differently - there are alternate thoughts on how the accountability and ultimately liability for female feticide can be spread, to factor in the parents’ preference for a male child, shaped by societal views. The ultrasonographer can record the sex of all fetuses and document it in a central database. Later, if the pregnancy is terminated, the family can become liable for the act. Here, the argument is that doctors are not the sole cause of gender imbalance, simply for revealing the sex of the child. The problem is actually societal, with a fascination for the male child.

M Tracy Hunter - Wikimedia Commons

M Tracy Hunter - Wikimedia Commons

In and of itself, the dynamics and debates surrounding the PCPNDT Act are wide-ranging and extensive, beyond the scope of this essay. The legal, medical, and social dimensions in solving these paradoxes need a detailed, perhaps separate discussion.

The Dhārmika Perspective

Were our śāstras silent on this? Śrī Nitin Sridhar, in his wonderful series of essays, Abortion: A Dharmic Perspective, explains that ancient Indians allowed legal abortion up to 16 weeks based on different factors, which took into consideration the larger Hindu concepts of karma, dharma, adharma, the individual jīva, and even prāyaścitta.. Abortion after 16 weeks involved legal punishments, while abortion before 16 weeks involved a 12-year prāyaścitta, or voluntary seeking of repentance through a specifically prescribed ritual procedure.

Nitin jī shows how Dhārmika texts perceive abortion as adharma, since it prevents the jīva from taking a physical birth: physical birth, which is that jīva’s entitlement based on their individual prārabdha karma. The Dhārmika texts enunciate that though the jīva associates with the fetus at conception, it actually enters the hṛdaya of the fetus only towards the fourth month of pregnancy. Thus, only the abortion performed after 16 weeks of pregnancy is like killing a person, while the abortion before 16 weeks prevents the jīva from self-identifying with the fetus. Therefore in ancient times, abortion after 16 weeks involved legal punishments, while abortion before 16 weeks involved a prāyaścitta.

However, the texts clearly say that after 16 weeks, termination is acceptable without adharma only if the purpose is to save the mother’s life.

Concluding Remarks

The ethical, moral, legal, medical, and social dimensions in addressing these issues require a nuanced and thoroughly comprehensive discussion. The ethical issues are only going to increase in the future, as modern science and technology evolves so that more diseases enter the domain of pre-delivery diagnosis, as unwanted conceptions increase, and as marriage is increasingly perceived in society as less necessary and/or becomes less valued.

These are very disturbing issues for society; but finally we must ask -

Is that society a healthy society, which does not accept a single abnormality outside its own definition of norms?

Some claim strongly that assessment of the maturity of a society is by how it deals with its members who cannot contribute anything: the handicapped, the old, the diseased, and even animals that are considered useless.

Are we going in the direction of immaturity despite the scientific progress?

In India, the trajectory of termination practices is often indifferent to the law, despite a general respect for it in many areas. That said, Indians have a remarkable readiness to accept Western discourses for application to Indian culture. This promises to make termination issues noisier in the future.

Can we evolve a sustainable, contemporary narrative and law on abortion, based on the eternal principles enunciated in the Dhārmika texts?

The texts are not morally obligatory or legally binding, contrary to what the colonials drilled into our collective minds. Intellectuals today can always craft policy and laws based on our Dhārmika philosophy, which are conducive to all.

Have we travelled too far on a ship of modernity, such that we look at tradition with only disdain?

References

- M Tracy Hunter

- Nitin Sridhar, “Abortion: A Dharmic Perspective”, Part 1, Part 2, Part 3, Part 4.